According to the world health organization

According to the world health organization

according to the World Health Organ

according to the World Health Organisation, malaria, a disease spread by mosquitoes, affects millions of people every year. Everyone knows how irritating the noise made by a mosquito,followed by a painful reaction to its bite, can be. It is astonishing that so little is known about why mosquitoes are drawn to or driven away from people, given the level of distress and disease caused by these insects. We know that the most effective chemical for protecting people against mosquitoes is diethyltoluamide, commonly shortened to deet. Though deet works well, it has some serious drawbacks: it can damage clothes and some people are allergic to it.

Scientists know that mosquitoes find some people more attractive than others, but they do not know why this should be. They also know that people vary in their reactions to mosquito bites. One person has a painful swelling while another who is bitten by the same mosquito may hardly notice. Scientists have not discovered the reason for this, but they have carried out experiments to show that mosquitoes are attracted to, or put off by, certain smells. In the future, scientists hope to develop a smell that mosquitoes cannot resist. This could be used in a trap so that, instead of attacking people, mosquitoes would fly into the trap and be destroyed. For the time being however, we have to continue spraying ourselves with unpleasant liquids if we want to avoid getting bitten.

Theo Tổ chức Y tế Thế giới, bệnh sốt rét, một bệnh lây truyền qua muỗi, ảnh hưởng đến hàng triệu người mỗi năm. Mọi người đều biết cách kích thích các tiếng ồn được thực hiện bởi một con muỗi, theo sau là một phản ứng đau đớn để cắn của nó, có thể được. Nó là đáng ngạc nhiên rằng rất ít thông tin về lý do tại sao muỗi được rút ra để định hướng hoặc cách xa mọi người, đưa ra mức độ căng thẳng và bệnh gây ra bởi các loài côn trùng. Chúng ta biết rằng các hóa chất hiệu quả nhất để bảo vệ con người chống lại muỗi là diethyltoluamide, thường được rút ngắn xuống còn DEET. Mặc dù DEET hoạt động tốt, nó có một số hạn chế nghiêm trọng: nó có thể làm hỏng quần áo và một số người bị dị ứng với nó. Các nhà khoa học biết rằng muỗi tìm thấy một số người trở nên hấp dẫn hơn những người khác, nhưng họ không biết tại sao điều này nên được. Họ cũng biết rằng những người khác nhau về phản ứng của họ để muỗi đốt. Một người có sưng đau trong khi một người bị cắn bởi muỗi cùng khó có thể nhận thấy. Các nhà khoa học đã không phát hiện ra lý do cho điều này, nhưng họ đã tiến hành các thí nghiệm để chứng minh rằng muỗi bị thu hút, hoặc đưa ra bởi, mùi nhất định. Trong tương lai, các nhà khoa học hy vọng phát triển một mùi mà muỗi không thể cưỡng lại. Điều này có thể được sử dụng trong một cái bẫy do đó, thay vì tấn công người, muỗi sẽ bay vào cái bẫy và bị tiêu diệt. Đối Tuy nhiên thời điểm hiện tại, chúng ta phải tiếp tục phun chính mình với chất lỏng khó chịu nếu chúng ta muốn tránh bị cắn.

Health

Health is a term that refers to a combination of the absence of illness, the ability to manage stress effectively, good nutrition and physical fitness, and high quality of life.

In any organism, health can be said to be a «state of balance,» or analogous to homeostasis, and it also implies good prospects for continued survival.

A widely accepted definition is that of the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations body that sets standards and provides global surveillance of disease. In its constitution, the WHO states that «health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.» In more recent years, this statement has been modified to include the ability to lead a «socially and economically productive life.»

The WHO definition is not without criticism, as some argue that health cannot be defined as a state at all, but must be seen as a process of continuous adjustment to the changing demands of living and of the changing meanings we give to life. The WHO definition is therefore considered by many as an idealistic goal rather than a realistic proposition.

Beginning in the 1950s with Halbert L. Dunn, and continuing in the 1970s with Donald B. Ardell, John Travis, Robert Allen and others, optimal health was given a broader, more inclusive interpretation called «wellness.»

Health is often monitored and sometimes maintained through the science of medicine, but can also be improved by individual health and wellness efforts, such as physical fitness, good nutrition, stress management, and good human relationships. Personal and social responsibility (those with means helping those without means) are fundamental contributors to maintenance of good health. (See health maintenance below).

Contents

In addition to the focus on individual choices and lifestyles related to health, other key areas of health include environmental health, mental health, population health, and public health.

Wellness

According to Dr. Donald B. Ardell, author of the best seller “High Level Wellness: An Alternative To Doctors, Drugs and Disease” (1986) and publisher of the Ardell Wellness Report, “wellness is first and foremost a choice to assume responsibility for the quality of your life. It begins with a conscious decision to shape a healthy lifestyle. Wellness is a mindset, a predisposition to adopt a series of key principles in varied life areas that lead to high levels of well-being and life satisfaction.”

Many wellness promoters like Ardell see wellness as a philosophy that embraces many principles for good health. The areas most closely affected by one’s wellness commitments include self-responsibility, exercise and fitness, nutrition, stress management, critical thinking, meaning and purpose or spirituality, emotional intelligence, humor and play, and effective relationships.

Health maintenance

Physical fitness, healthy eating, stress management, a healthy environment, enjoyable work, and good human relationship skills are examples of steps to improve one’s health and wellness.

Physical fitness has been shown to reduce the risk of dying prematurely, developing heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and colon cancer. It has also been shown to reduce feelings of anxiety and depression, control weight, and help improve overall psychological well-being.

Healthy eating has been linked to the prevention and treatment of many diseases, especially cancer, heart disease, hypoglycemia, and diabetes. Overall, people with healthy eating habits feel better, keep up strength and energy, manage weight, tolerate treatment-related side effects, decrease the risk of infection, and heal and recover more quickly. Studies have also shown a correlation between persons with a hypoglycemia and crime. For persons with adult onset diabetes, in some cases healthy eating can reduce or eliminate the need for insulin.

Researchers have long known that stress management can help people reduce tension, anxiety, and depression, as well as help people cope with life challenges more effectively. Stress management can also assist persons in having more satisfying human relationships, job satisfaction and a sense of life purpose. Duke University Medical Center researchers have recently found that stress may also provide cardiovascular health as well.

A good environment that has clean and safe drinking water, clean air, is relatively free of toxic elements, and not overcrowded, can increase life expectancy significantly. Environmental Health is becoming an increasingly important consideration for causes of premature death.

Wellness workplace programs are recognized by an increasingly large number of companies for their value in improving health and well-being of their employees, and increasing morale, loyalty, and productivity at work. A company may provide a gym with exercise equipment, start smoking cessation programs, and provide nutrition, weight, or stress management training. Other programs may include health risk assessments, safety and accident prevention, and health screenings. Some workplaces are working together to promote entire healthy communities. One example is through the Wellness Council of America. [1]

Environmental health

Environmental health comprises those aspects of human health, including quality of life, that are determined by physical, chemical, biological, social, and psychosocial factors in the environment. It also refers to the theory and practice of assessing, correcting, controlling, and preventing those factors in the environment that can potentially affect adversely the health of present and future generations [2]

Environmental health, as used by the WHO Regional Office for Europe, includes both the direct pathological effects of chemicals, radiation, and some biological agents, and the effects (often indirect) on health and wellbeing of the broad physical, psychological, social, and aesthetic environment, which includes housing, urban development, land use, and transport.

Nutrition, soil contamination, water pollution, air pollution, light pollution, waste control, and public health are integral aspects of environmental health.

In the United States, the Center for Disease Control Environmental Health programs include: air quality, bioterrorism, environmental hazards and exposure, food safety, hazardous substances, herbicides, hydrocarbons, lead, natural disasters, pesticides, smoking and tobacco use, water quality, and urban planning for healthy places. [3]

While lifestyles have been by far the leading factor in premature deaths, environmental factors is the second leading cause and has been increasing in its importance for health over the past several decades.

Environmental health services are defined by the World Health Organization as:

those services that implement environmental health policies through monitoring and control activities. They also carry out that role by promoting the improvement of environmental parameters and by encouraging the use of environmentally friendly and healthy technologies and behaviors. They also have a leading role in developing and suggesting new policy areas.

The Environmental Health profession had its modern-day roots in the sanitary and public health movement of the United Kingdom. This was epitomized by Sir Edwin Chadwick, who was instrumental in the repeal of the poor laws and was the founding president of the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health.

Mental health

Mental health is a concept that refers to a human individual’s emotional and psychological well-being. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines mental health as «A state of emotional and psychological well-being in which an individual is able to use his or her cognitive and emotional capabilities, function in society, and meet the ordinary demands of everyday life.»

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there is no one «official» definition of mental health:

Mental health has been defined variously by scholars from different cultures. Concepts of mental health include subjective well-being, perceived self-efficacy, autonomy, competence, intergenerational dependence, and self-actualization of one’s intellectual and emotional potential, among others. From a cross-cultural perspective, it is nearly impossible to define mental health comprehensively. It is, however, generally agreed that mental health is broader than a lack of mental disorders. [4]

Cultural differences, subjective assessments, and competing professional theories all affect how «mental health» is defined. In general, most experts agree that «mental health» and «mental illness» are not opposites. In other words, the absence of a recognized mental disorder is not necessarily an indicator of mental health.

One way to think about mental health is by looking at how effectively and successfully a person functions. Feeling capable and competent, being able to handle normal levels of stress, maintaining satisfying relationships, leading an independent life, and being able to «bounce back,» or recover from difficult situations are all signs of mental health.

Mental health, as defined by the U.S. Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health, «refers to the successful performance of mental function, resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with other people, and the ability to adapt to change and cope with adversity.»

Some experts consider mental health as a continuum with the other end of the continuum being mental disorders. Thus, an individual’s mental health may have many different possible values. Mental wellness is generally viewed as a positive attribute, such that a person can reach enhanced levels of mental health, even if they do not have any diagnosable mental illness. This definition of mental health highlights emotional well being as the capacity to live a full and creative life, with the flexibility to deal with life’s inevitable challenges. Some mental health experts and health and wellness promoters are now identifying the capability for critical thinking as a key attribute of mental health as well. Many therapeutic systems and self-help books offer methods and philosophies espousing presumably effective strategies and techniques for further improving the mental wellness of otherwise healthy people.

Population health

Population health is an approach to health that aims to improve the health of an entire population. One major step in achieving this aim is to reduce health inequities among population groups. Population health seeks to step beyond the individual-level focus of mainstream medicine and public health by addressing a broad range of factors that impact health on a population-level, such as environment, social structure, resource distribution, and so forth.

Population health reflects a shift in thinking about health as it is usually defined. Population health recognizes that health is a resource and a potential as opposed to a static state. It includes the potential to pursue one’s goals to acquire skills and education and to grow.

An important theme in population health is importance of social determinants of health and the relatively minor impact that medicine and healthcare have on improving health overall. From a population health perspective, health has been defined not simply as a state free from disease but as «the capacity of people to adapt to, respond to, or control life’s challenges and changes.» [5]

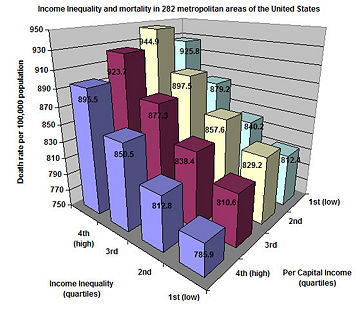

Recently, there has been increasing interest from epidemiologists on the subject of economic inequality and its relation to the health of populations. There is a very robust correlation between socioeconomic status and health. This correlation suggests that it is not only the poor who tend to be sick when everyone else is healthy, but that there is a continual gradient, from the top to the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder, relating status to health. This phenomenon is often called the «SES Gradient.» Lower socioeconomic status has been linked to chronic stress, heart disease, ulcers, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, certain types of cancer, and premature aging.

Population health parameters indicate, for example, that the economic inequality within the United States is a factor that explains why the United States ranks only 30th in life expectancy, right behind Cuba. which is 29th. All 29 countries that rank better than the United States have a much smaller gap of income distribution between their richest and poorest citizens.

Despite the reality of the SES Gradient, there is debate as to its cause. A number of researchers (A. Leigh, C. Jencks, A. Clarkwest) see a definite link between economic status and mortality due to the greater economic resources of the better-off, but they find little correlation due to social status differences. Other researchers (such as R. Wilkinson, J. Lynch, and G. A. Kaplan) have found that socioeconomic status strongly affects health even when controlling for economic resources and access to health care.

Most famous for linking social status with health are the Whitehall studies—a series of studies conducted on civil servants in London. The studies found that, despite the fact that all civil servants in England have the same access to health care, there was a strong correlation between social status and health. The studies found that this relationship stayed strong even when controlling for health-effecting habits such as exercise, smoking, and drinking. Furthermore, it has been noted that no amount of medical attention will help decrease the likelihood of someone getting type 1 diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis—yet both are more common among populations with lower socioeconomic status. Lastly, it has been found that among the wealthiest quarter of countries on earth (a set stretching from Luxembourg to Slovakia), there is no relation between a country’s wealth and general population health, suggesting that past a certain level, absolute levels of wealth have little impact on population health, but relative levels within a country do. [6]

The concept of psychosocial stress attempts to explain how psychosocial phenomenon such as status and social stratification can lead to the many diseases associated with the SES Gradient. Higher levels of economic inequality tend to intensify social hierarchies and generally degrades the quality of social relations, leading to greater levels of stress and stress related diseases. Wilkinson found this to be true not only for the poorest members of society, but also for the wealthiest. Economic inequality is bad for everyone’s health.

Inequality does not affect only the health of human populations. D. H. Abbott at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center found that among many primate species, those with less egalitarian social structures correlated with higher levels of stress hormones among socially subordinate individuals. Research by R. Sapolsky of Stanford University provides similar findings.

Public health

Public health is concerned with threats to the overall health of a community based on population health analysis.

The size of the population in question can be limited to a dozen or less individuals, or, in the case of a pandemic, whole continents. Public health has many sub-fields, but is typically divided into the categories of epidemiology, biostatistics, and health services. Environmental, social and behavioral health, and occupational health are also important fields in public health.

The focus of a public health intervention is to prevent, rather than treat a disease, through surveillance of cases and the promotion of healthy behaviors. In addition to these activities, in many cases treating a disease can be vital to preventing it in others, such as during an outbreak of an infectious disease such as HIV/AIDS. Vaccination programs, distribution of condoms, and promotion of abstinence or fidelity in marriage are examples of public health measures advanced in various countries.

Many countries have their own government agencies, sometimes known as ministries of health, to respond to domestic health issues. In the United States, the frontline of public health initiatives are state and local health departments. The Surgeon General-led United States Public Health Service, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, although based in the United States, are also involved with several international health issues in addition to their national duties.

All of the areas of health, including individual health and wellness, environmental health, mental health, population health, and public health now need to be viewed in a global context. In a global society, the health of every human being is relevant to the health of each one of us. For example, a disease outbreak in one part of the world can quickly travel to other regions and continents, via international travel, creating a global problem.

Global health requires that the world’s citizens collaborate to improve all types of health in all nations, rich or poor, and seek to prevent, reduce, and stop disease outbreaks at their source.

Notes

References

External links

All links retrieved March 18, 2020.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Перевод «the world health organization to» на русский

Всемирной организацией здравоохранения для

Vsemirnoy organizatsiyey zdravookhraneniya dlya

11 примеров, содержащих перевод

Всемирную организацию здравоохранения

Vsemirnuyu organizatsiyu zdravookhraneniya

9 примеров, содержащих перевод

Всемирной организации здравоохранения по

Vsemirnoy organizatsii zdravookhraneniya po

8 примеров, содержащих перевод

Всемирной организацией здравоохранения в целях

Vsemirnoy organizatsiyey zdravookhraneniya v tselyakh

3 примеров, содержащих перевод

что Всемирная организация здравоохранения

chto Vsemirnaya organizatsiya zdravookhraneniya

3 примеров, содержащих перевод

Всемирной организацией здравоохранения в том, что касается

Vsemirnoy organizatsiyey zdravookhraneniya v tom, chto kasayetsya

2 примеров, содержащих перевод

ВОЗ, чтобы

VOZ, chtoby

2 примеров, содержащих перевод

Всемирной организацией здравоохранения с целью

Vsemirnoy organizatsiyey zdravookhraneniya s tsel’yu

2 примеров, содержащих перевод

Всемирной организацией здравоохранения в вопросе

Vsemirnoy organizatsiyey zdravookhraneniya v voprose

What Does the World Health Organization Do?

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) is the UN agency charged with spearheading international public health efforts. Over its nearly seventy-five years, the WHO has logged both successes, such as eradicating smallpox, and perceived failures, such as its delayed response to the Ebola outbreak in 2014.

In response, the WHO has undertaken reforms to improve its ability to fight future epidemics and boost the health of the hundreds of millions of people still living in extreme poverty. However, the WHO is in an uphill battle to loosen its rigid bureaucracy and it faces an increasingly troublesome budget. The COVID-19 pandemic has proved to be another monumental challenge for the health agency, sparking fresh debate over its effectiveness.

Why was the WHO established?

Created in 1948 as part of the United Nations, the WHO has a broad mandate to guide and coordinate international health policy. Its primary activities include developing partnerships with other global health initiatives, conducting research, setting norms, providing technical support, and monitoring health trends around the world. Over the decades, the WHO’s remit has expanded from its original focus on women’s and children’s health, nutrition, sanitation, and fighting malaria and tuberculosis.

What does the WHO do?

A summary of global news developments with CFR analysis delivered to your inbox each morning. Most weekdays.

The World This Week

A weekly digest of the latest from CFR on the biggest foreign policy stories of the week, featuring briefs, opinions, and explainers. Every Friday.

Think Global Health

A curation of original analyses, data visualizations, and commentaries, examining the debates and efforts to improve health worldwide. Weekly.

Today, the WHO monitors and coordinates activities concerning many health-related issues, including genetically modified foods, climate change, tobacco and drug use, and road safety. The WHO is also an arbiter of norms and best practices. Since 1977, the organization has maintained a list of essential medicines it encourages hospitals to stock; it has since made a similar list of diagnostic tests. The agency also provides guidance on priority medical devices, such as ventilators and X-ray and ultrasound machines.

Some of the WHO’s most lauded successes include its child vaccination programs, which contributed to the eradication of smallpox in 1979 and a 99 percent reduction in polio infections in recent decades, and its leadership during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic. The agency has the exclusive authority to declare global health emergencies, which it has done several times since its members granted it the power in 2007. At present, the WHO’s work includes combating the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergencies, as well as promoting refugees’ health.

In its 2019 strategy, the WHO identified three priorities [PDF] for its work over the next five years:

The WHO’s strategic priorities are rooted in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, a set of seventeen objectives for ending poverty by 2030.

How is the WHO governed?

The WHO is headquartered in Geneva and has six regional and 150 country offices. It is controlled by delegates from its 194 member states, who vote on policy and elect the director general. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, previously Ethiopia’s foreign minister, was elected to a five-year term in 2017 and reelected in 2022. He is the WHO’s first leader from Africa, and his election was the first time all WHO countries had an equal vote.

WHO delegates set the agency’s agenda and approve an aspirational budget each year at the World Health Assembly. The director general is responsible for raising the lion’s share of funds from donors.

What is the WHO’s budget?

The WHO has become increasingly dependent on voluntary contributions, which puts pressure on the organization to align its goals with those of its donors.

Some experts argued that the Trump administration’s moves seriously threatened the body’s effectiveness and cited budget cuts as a major factor in the WHO’s slow response to outbreaks. The eradication of polio could also place financial stress on the WHO, whose budget has for decades been bolstered by polio funding, and on lower-income countries that rely on international funding to keep up surveillance and immunization efforts.

How does the WHO fight global health emergencies?

Under the International Health Regulations (IHR), a legally binding framework drawn up in 2005 to prevent and mitigate health emergencies, WHO member states are required to monitor and report potential crises. Countries have historically been hesitant to report outbreaks, often because they’re fearful of economic repercussions. In 2003, for example, China denied for months that it was suffering an outbreak of the infectious disease that was eventually identified as SARS. Before the WHO declared China free of SARS in 2004, the disease killed more than three hundred people. In Ethiopia, Tedros himself was accused of downplaying cholera outbreaks while he was the country’s health minister; he denied these claims.

In an extraordinary crisis, the WHO can declare a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), which it has done six times: during the 2009 swine flu (H1N1) epidemic; in reaction to a reversal of progress in eradicating polio in 2014; amid the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa; during the 2016 Zika virus outbreak in the Americas; once the ongoing Ebola epidemic reached the city of Goma in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2019; and amid the global outbreak of the new coronavirus in 2020.

During a PHEIC, the WHO issues nonbinding guidance to its members on how they should respond to the emergency, including on potential travel and trade restrictions. It seeks to prevent countries in the surrounding region and beyond from overreacting and inflicting undue economic harm on the country in crisis. The WHO has hoped this would encourage affected countries to report outbreaks in a timely manner. However, experts say that, despite the WHO’s guidance, many countries continue to impose damaging travel and trade restrictions, a problem that was laid bare during the Ebola and COVID-19 crises. In an emergency, the WHO also spells out treatment guidelines and acts as a global coordinator, shepherding scientific data and experts to where they are most needed.

Additionally, the WHO provides guidance and coordination for emergencies that don’t rise to the level of a PHEIC. But declaring a PHEIC can help speed up international action and often encourages research on the disease in question, even if there is little risk of a pandemic. This was particularly true for the 2014 declaration for polio. At the same time, PHEIC declarations are contentious, and some argue that they can exacerbate ongoing outbreaks.

How has the WHO responded to COVID-19?

As it has done in past health crises, the WHO has provided medical and technical guidance as its experts investigate the virus, particularly new variants, as well as coordinated with world leaders on their national responses. It has also distributed critical supplies to member states, including millions of diagnostic tests and personal protective equipment for health-care workers. Additionally, it has helped to lead the global vaccination effort: the WHO partnered with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to launch COVAX, a global initiative aimed at providing equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. By mid-2022, COVAX had delivered about 1.5 billion doses, falling short of its goal to distribute 2 billion by the end of 2021.

However, the WHO’s response has been the subject of controversy. Many experts have raised concerns about the agency’s deference to Beijing and increasing Chinese influence over the institution. Among other criticisms, they say WHO officials accepted misinformation from the Chinese government as the outbreak unfolded, waited too long to declare an emergency, and have shunned Taiwan because of bias toward China. Trump was particularly critical of the agency and in May 2020 he announced an end to the U.S. relationship with the WHO. (Biden reversed course on the U.S. exit immediately after taking office.) In January 2021, a delegation of WHO scientists traveled to Wuhan to investigate the virus’s origin, though its findings were inconclusive and critics say Beijing constrained the group’s work. The WHO has since established a new advisory group to continue research on the issue.

What reforms has the WHO made?

Under Tedros, the WHO has tackled another of its most enduring problems: political friction between its headquarters and its six regional offices, which critics say have enjoyed too much autonomy. Some say that tension between Geneva and the WHO’s Africa office, in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, contributed to the agency’s poor response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak. To assert its authority over these regional power bases, the WHO has begun requiring staff to rotate among posts around the world, similar to a policy at UNICEF. While some observers paint this and other changes as merely cosmetic, others have applauded the reforms. “There is much greater cooperation than there was in the past,” global health expert Ilona Kickbusch said at a 2020 CFR meeting.

More recently, the COVID-19 crisis has prompted calls for major reforms. In a rare special session of the WHO’s World Health Assembly in 2021, delegates initiated the drafting of a global treaty on pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response. The proposal for a pandemic treaty has sparked debate, however, and the deliberation process could take years. At the 2022 assembly, countries agreed on a U.S.-led proposal to strengthen the IHR by increasing member states’ accountability around disease outbreaks, though no changes have been formally approved.

“Pleas for strengthening the WHO have remained prominent,” writes CFR’s David P. Fidler for Think Global Health. “However, this goal faces serious obstacles,” Fidler says, namely resistance from China, Russia’s war in Ukraine, and a lack of strong U.S. support for expanding the body’s authority and funding.

Recommended Resources

On The President’s Inbox podcast, CFR’s Stewart M. Patrick lays out what the WHO can and cannot do.

For Think Global Health, CFR’s David P. Fidler looks at the World Health Assembly’s slow steps toward global health reforms.

This CFR Independent Task Force report argues that the WHO has an important leadership role in public health emergencies but lacks the geopolitical heft to address their broader implications.

In Foreign Affairs, Laurie Garrett examines the WHO’s mishandling of the 2014 Ebola outbreak.

Plagues and the Paradox of Progress, a 2018 book by CFR’s Thomas J. Bollyky, discusses the WHO’s attempts to improve itself after the Ebola crisis.

This CFR Backgrounder describes ongoing global efforts to eradicate polio.

World Health Organization

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Read a brief summary of this topic

World Health Organization (WHO), French Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) established in 1948 to further international cooperation for improved public health conditions. Although it inherited specific tasks relating to epidemic control, quarantine measures, and drug standardization from the Health Organization of the League of Nations (set up in 1923) and the International Office of Public Health at Paris (established in 1907), WHO was given a broad mandate under its constitution to promote the attainment of “the highest possible level of health” by all peoples. WHO defines health positively as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Each year WHO celebrates its date of establishment, April 7, 1948, as World Health Day.

With administrative headquarters in Geneva, governance of WHO operates through the World Health Assembly, which meets annually as the general policy-making body, and through an Executive Board of health specialists elected for three-year terms by the assembly. The WHO Secretariat, which carries out routine operations and helps implement strategies, consists of experts, staff, and field workers who have appointments at the central headquarters or at one of the six regional WHO offices or other offices located in countries around the world. The agency is led by a director general nominated by the Executive Board and appointed by the World Health Assembly. The director general is supported by a deputy director general and multiple assistant directors general, each of whom specializes in a specific area within the WHO framework, such as family, women’s, and children’s health or health systems and innovation. The agency is financed primarily from annual contributions made by member governments on the basis of relative ability to pay. In addition, after 1951 WHO was allocated substantial resources from the expanded technical-assistance program of the UN.

WHO officials periodically review and update the agency’s leadership priorities. Over the period 2014–19, WHO’s leadership priorities were aimed at:

1. Assisting countries that seek progress toward universal health coverage

2. Helping countries establish their capacity to adhere to International Health Regulations

3. Increasing access to essential and high-quality medical products

4. Addressing the role of social, economic, and environmental factors in public health

5. Coordinating responses to noncommunicable disease

6. Promoting public health and well-being in keeping with the Sustainable Development Goals, set forth by the UN.

The work encompassed by those priorities is spread across a number of health-related areas. For example, WHO has established a codified set of international sanitary regulations designed to standardize quarantine measures without interfering unnecessarily with trade and air travel across national boundaries. WHO also keeps member countries informed of the latest developments in cancer research, drug development, disease prevention, control of drug addiction, vaccine use, and health hazards of chemicals and other substances.

WHO sponsors measures for the control of epidemic and endemic disease by promoting mass campaigns involving nationwide vaccination programs, instruction in the use of antibiotics and insecticides, the improvement of laboratory and clinical facilities for early diagnosis and prevention, assistance in providing pure-water supplies and sanitation systems, and health education for people living in rural communities. These campaigns have had some success against AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and a variety of other diseases. In May 1980 smallpox was globally eradicated, a feat largely because of the efforts of WHO. In March 2020 WHO declared the global outbreak of COVID-19, a severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus that first appeared in Wuhan, China, in late 2019, to be a pandemic. The agency acted as a worldwide information centre on the illness, providing regular situation reports and media briefings on its spread and mortality rates; dispensing technical guidance and practical advice for governments, public health authorities, health care workers, and the public; and issuing updates of ongoing scientific research. As pandemic-related infections and deaths continued to mount in the United States, Pres. Donald J. Trump accused WHO of having conspired with China to conceal the spread of the novel coronavirus in that country in the early stages of the outbreak. In July 2020 the Trump administration formally notified the UN that the United States would withdraw from the agency in July 2021. The U.S. withdrawal was halted by Trump’s successor, Pres. Joe Biden, on the latter’s first day in office in January 2021.

In its regular activities WHO encourages the strengthening and expansion of the public health administrations of member nations, provides technical advice to governments in the preparation of long-term national health plans, sends out international teams of experts to conduct field surveys and demonstration projects, helps set up local health centres, and offers aid in the development of national training institutions for medical and nursing personnel. Through various education support programs, WHO is able to provide fellowship awards for doctors, public-health administrators, nurses, sanitary inspectors, researchers, and laboratory technicians.

World Health Organization’s Ranking of the World’s Health Systems

Some people fancy all health care debates to be a case of Canadian Health Care vs. American. Not so. According to the World Health Organization’s ranking of the world’s health systems, neither Canada nor the USA ranks in the top 25.

Improving the Canadian Healthcare System does not mean we must emulate the American system, but it may mean that perhaps we can learn from countries that rank better than both Canada and the USA at keeping their citizens healthy.

World Health Organization Ranking; The World’s Health Systems

| 1 France 2 Italy 3 San Marino 4 Andorra 5 Malta 6 Singapore 7 Spain 8 Oman 9 Austria 10 Japan 11 Norway 12 Portugal 13 Monaco 14 Greece 15 Iceland 16 Luxembourg 17 Netherlands 18 United Kingdom 19 Ireland 20 Switzerland 21 Belgium 22 Colombia 23 Sweden 24 Cyprus 25 Germany 26 Saudi Arabia 27 United Arab Emirates 28 Israel 29 Morocco 30 Canada 31 Finland 32 Australia 33 Chile 34 Denmark 35 Dominica 36 Costa Rica 37 USA 38 Slovenia 39 Cuba 40 Brunei 41 New Zealand 42 Bahrain 43 Croatia 44 Qatar 45 Kuwait 46 Barbados 47 Thailand 48 Czech Republic 49 Malaysia 50 Poland 51 Dominican Republic 52 Tunisia 53 Jamaica 54 Venezuela 55 Albania 56 Seychelles 57 Paraguay 58 South Korea 59 Senegal 60 Philippines 61 Mexico 62 Slovakia 63 Egypt 64 Kazakhstan | 65 Uruguay 66 Hungary 67 Trinidad and Tobago 68 Saint Lucia 69 Belize 70 Turkey 71 Nicaragua 72 Belarus 73 Lithuania 74 Saint Vincent and the Grenadines 75 Argentina 76 Sri Lanka 77 Estonia 78 Guatemala 79 Ukraine 80 Solomon Islands 81 Algeria 82 Palau 83 Jordan 84 Mauritius 85 Grenada 86 Antigua and Barbuda 87 Libya 88 Bangladesh 89 Macedonia 90 Bosnia-Herzegovina 91 Lebanon 92 Indonesia 93 Iran 94 Bahamas 95 Panama 96 Fiji 97 Benin 98 Nauru 99 Romania 100 Saint Kitts and Nevis 101 Moldova 102 Bulgaria 103 Iraq 104 Armenia 105 Latvia 106 Yugoslavia 107 Cook Islands 108 Syria 109 Azerbaijan 110 Suriname 111 Ecuador 112 India 113 Cape Verde 114 Georgia 115 El Salvador 116 Tonga 117 Uzbekistan 118 Comoros 119 Samoa 120 Yemen 121 Niue 122 Pakistan 123 Micronesia 124 Bhutan 125 Brazil 126 Bolivia 127 Vanuatu | 128 Guyana 129 Peru 130 Russia 131 Honduras 132 Burkina Faso 133 Sao Tome and Principe 134 Sudan 135 Ghana 136 Tuvalu 137 Ivory Coast 138 Haiti 139 Gabon 140 Kenya 141 Marshall Islands 142 Kiribati 143 Burundi 144 China 145 Mongolia 146 Gambia 147 Maldives 148 Papua New Guinea 149 Uganda 150 Nepal 151 Kyrgystan 152 Togo 153 Turkmenistan 154 Tajikistan 155 Zimbabwe 156 Tanzania 157 Djibouti 158 Eritrea 159 Madagascar 160 Vietnam 161 Guinea 162 Mauritania 163 Mali 164 Cameroon 165 Laos 166 Congo 167 North Korea 168 Namibia 169 Botswana 170 Niger 171 Equatorial Guinea 172 Rwanda 173 Afghanistan 174 Cambodia 175 South Africa 176 Guinea-Bissau 177 Swaziland 178 Chad 179 Somalia 180 Ethiopia 181 Angola 182 Zambia 183 Lesotho 184 Mozambique 185 Malawi 186 Liberia 187 Nigeria 188 Democratic Republic of the Congo 189 Central African Republic 190 Myanmar |

125 Comments

France’s excellence in health care delivery is probably due to two major factors: 1) it is extraordinarily open and communicative with patients and families which reaps significant patient safety benefits; and 2) it has far more doctors per capita so physicians want patients and patients get a choice.

I lived in France and you can go to a pharmacist and be diagnosed for common ailments and walk out with an Rx in 15 mins. Bad ass!

French have a real Universal Healthcare System and unlike we Americans are not stupid to call it Socialistic Healthcare System. As much as military industrial complex for its own benefits unjustly frightened us from Socialism, Private Insurance Industry for same goal, with using same tactic an same word, frightening us from Universal Healthcare System, and as much as we were stupid in believing MIC bull shits, we are stupid in believing PII bull shits. Of course a corrupt and criminal party like Republican Party in harmony with a do nothing but talk too much, but as much corrupt party like Democratic Party helping them as much as they can, but main factor is our own absolute ignorance and stupidity.

Universal health care is socialized medicine.

And why exactly is that bad? Sorry, when the US is ranked so low, despite the highest health expenditure in the world, maybe you need to let go of ideology and actually look at some evidence.

Under socialized medicine population health and minimizing public health care costs always trump what’s best for individual patients. It’s one thing for a person to voluntarily give up their freedom to a health care collective promising free health care for all. But it’s a whole different thing if that person or group of persons summons the power of government to forcibly remove the freedom of others.

I totally disagree with Heather… The evidence is apparent in the rankings…. Private healthcare is far more frightening than socialized and far less effective: when health has a profit making motive, you will never reap the benefits of excellent healthcare. The only problem you have with socialized healthcare is that it fully depends on the motivations of your government and how apathetic the population are when it comes to legislative changes that curb things that were previously considered rights. Im from the UK and i can say that the NHS was fantastic though it has declined since tony blair first started to cut its funding… This has been exacerbated under david ham head cameron! But i would much rather have the NHS than an american style alternative… Nixon even said that the US healthcare system had a profit making motive, i do worry that we, in the UK are heading in the same way…. I have much empathy for americans who have suffered or lost prople as a result of that system. Everyone should have the right to healthcare.

Helen,

The profit motive helps drive innovation and excellence in health care.

People from countries around the world travel to the US for health care.

It’s wrong to force citizens to depend on the motivations of their government for access to health care. Everyone should have the freedom to spend their own money on their own health care in their own country.

Heather,

no the profit motive does not inspire innovation, if that be the case with the way we spend and go for profit we would have the number one health system, with a much lower negative outcomes, and way better access to care. To profit off of illness is a sick sad, and disgusting way to run a system. If the government is to make decisions on how healthcare is run then that would work best in a country with no parliament and direct voting. if we use the democratic processes we founded this country on (in Ideology) then the government would have to run it the way the people want it.

What’s wrong with the profit motive? Every employee in a public health care system personally benefits from the profit motive. The only difference under a public health care system is that the government controls the profit motive and decides which groups and corporations will benefit the most. Democracy works best with a limited government otherwise the biggest groups end up calling the shots for the rest of us.

Heather: Private healthcare DOES NOT “drive innovation and excellence in health care” – it makes doctors over-prescribe (for commission on medicine) and request useless tests that are not needed, just because it will make the hospital more money.

About 6 months later I moved to Spain (public health service) – went to hospital and found out I have a malignant tumor and needed an operation urgently to remove it.

Private healthcare also demands that the doctors can charge whatever they like and if you don’t like/can’t afford then you don’t get treatment.

There should always be the choice of public and private, but it should be the right of every citizen to have access to basic healthcare.

Robert,

A free market offering choice, competition, and price transparency does drive innovation and excellence by increasing quality and reducing price. Misdiagnosis can happen in private or public health care. Doctors who place profits ahead of providing high quality medical services to their patients can be found practicing in private and public health care systems (i.e. fraudulent Medicare claims). In a free market these doctors would soon find themselves out of business, but here in Saskatchewan doctors are paid by Medicare regardless of the quality of care provided.

Public health care demands that doctors help ration care to save the system money. Here in Saskatchewan the regional health authorities allocate money to diagnostic tests and surgeries. If your regional health authority can’t afford it then you don’t get treatment which is why we have government-mandated waiting lists.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms doesn’t guarantee a right to benefits from a government program like Medicare – nor should it. What is unjust in a free and democratic society is that a government monopoly on health care not only infringes on our legal “…right to life, liberty and security of the person…” but leaves no option for escaping the harms caused by this infringement.

Is there a rubric to the rankings. If you look at patents on medicinal items, Israel is first, and American is 2nd. If the rubric has 20% of its value on being affordable (whatever that means), and 20% on survival rates, then I disagree. I’d rather be alive and broke than dead with money. If there is a high percentage on low costs, but no reference to innovative discoveries, I also disagree. In short, without the rubric for judging systems, this “ranking” is meaningless.

It’s strange how Americans trust private profit driven organisation’s over their own government. When we use the private sector in the UK it’s very rarely has a good outcome. You’re government tries to do the best by its people or we vote them out. In the UK you can still have private healthcare and pay insurance and about 11% of people do. This is choice in the US if you get cancer the chances you will go bankrupt. In the European countries all your treatment is paid for, prescriptions are often free for a number of years after diagnosis. In most European countries the life expectancy is higher than the US and we spend much less than the US. People need too look at the facts and move away from their suspicions of socialised. Trust me if I’m ill I don’t worry about money I just go to the doctor, no it’s not perfect but it’s better than going bankrupt.

These comparisons are for the most part meaningless, yet we keep trudging them out as if there was some gem to be revealed. All of the data comes from self-reporting entities. There’s no standardization and there’s very little commonality. That’s why you’ll see similar national health care systems have significantly different rankings. If outcomes were measured consistently, we’d see consistency in the rankings. (no one every explains why we don’t because that wouldn’t further an agenda) I’ve seen one “study” ranking UK as #1, which this ranking has them quite a bit further down the list. So why the disparity? I don’t suppose it would be that there are certain incentives that certain providers receive based on certain data? (Naw that would harken to much back to the days of the USSR.) The US usually ranks lower in these studies because there is less incentive to hide data-sets or pad stats on outcomes. Do we not see some correlation between the incentives provided by governments as part of reimbursement and the outcomes that get reported? Is there any disincentive in those very same countries for skewing self-reported data? I know people will want to believe what they want to believe, but to rely on these data sets as being meaningful for policy positions is to build your house out of a deck of cards. (remember My Cousin Vinny? seems like P.T. Barnum is alive and well.)

It’s bad because our government says it’s bad (for profit). A society of sheep that think they are individuals.

No true… these are just political terms… the question and debate is deeper than politics. notably, is healthcare a basic human “right” or a “privilege?” I’m an american living in France and can tell you the french system works because the french see healthcare as a human rights issue. Right or wrong, good or bad, this is the french mentality. This debate in the US will only be resolved when we can answer this question. Free market capitalism favors healthcare as privilege and its in the blood of every American (republican, democrat, etc.) Like it or not, this is who we are… This is how our society was built. The french see paying taxes to support their healthcare system as totally reasonable. Taxes are an anathema to almost every American.

‘Taxes are anathema to almost every American’? Please. It’s the ridiculously low tax rates of the 1% and the hugely unequal business taxes that favor large corporations that are anathema to any American with a brain, including not a few of the 1%.

Government is an essential component of Democracy. Taxes are like dues to be a member of the democracy. Do I want my life run by huge corporations? No, I want a government that can control those corporations whose only duty is their executives and their largest shareholders. Your outlook is strictly a Republican outlook. It may be shared by some Democrats, but not many. I’m 66. I grew up with an anesthisiologist at each and of the dinner table. I was for National Health Care then and I am for it now, even more so. My sister-in-law is a Harvard MS family doc who is extremely discourage with the devolution of US healthcare into the mess that it now is. To whatever degree the ACA struggles it is largely due to 60 yrs+ of Republican intransigence and the disfunctional system that very few Europeans would sacrifice their access to their system to be part of ours. Relatively few Canadians live in Seattle and very few Europeans. Healthcare is one of the reasons. I know now what an extortionary, corrupt system we have created by pretending that free market’s are good to begin with and that we ever had a free market in US healthcare. Free markets do not exist where pricing is not transparent. Healthcare is the most expensive thing in most Americans lives but nobody, including the doctors knows the price of any medical service. So if you wanted to compare prices from one place to the other, or given the extreme costs in the US, send out your procedure for bids. I don’t think so.

Once again this is a system that has been completely taken over by huge corporations.

Secondly when you restrict the number of physicians both internally and externally (from outside the US) it is absolutely NOT a free market. This has been going on since I was a kid in the 50s at least. France has 50% more physicians/capita than the US.

Heather isn’t thinking. There are many thing wrong with her story. Most basically, whereas she reveres competition as a trait of capitalism as most of its defenders do, every capitalist from day one strives and struggles to eliminate competition, and by eliminating competition they have brought us to a place of less choice due to 6 major Big Banks, 5 manufacturers of household appliances, a handful of major health insurance companies, and on and on. And the profits that she praises and defends mean health insurance companies, to increase profits, are motivated to find innovative ways to pay out less in benefits while charging more for premiums.

No, it is not. You should learn vocabulary.

Heather, you and people like you are the problem. The GOP has you buffaloed with their scare tactics.

What scare tactics? This is real life.

real world – a great society cannot be borne of the elderly and infirmed. People are made to suffer to what end?

Wrong. Bismark model in Germany is completely privatized and there is universal coverage.

of course, only a Republican would dig their heels in to protect the WORST health system in the developed world. The American “your-money-or-your-life” health non-system consistently ranks DEAD (no pun intended) LAST or next to last in all positive measures (quality, accessibility, affordability, outcomes, healthy lives) but it makes a FEW VERY RICH to deny other access to affordable care – so, to Republicans, it’s the “best” system in the world and must be protected!

Call it what you want but it does work better than our current system

And that seems to be a very good thing in this case. In America, we are made by the government to have insurance on our cars, our public schools are paid for by taxes, our public libraries, too. The list is rather long, and we haven’t all been put in chains. Time to recognize the new world, folks. Universal coverage just sounds better to those who are so paranoid about socialism. It’s just a word.

Socialism is not just a word in Venezuela.

Fast forward to today August 3rd 2017………..now tell that to the UK baby, the hospital held that baby hostage……….WOULDN’T ALLOW IT TO COME TO THE US, FOR TREATMENT, EVEN THOU THE PARENTS HAD RAISED MONEY TO COME, SO YOU SOCIALIST CAN TAKE YOUR UNIVERSAL CARE AND SHOVE IT WHERE THE SUN DON’T SHINE.

Medicare is socialized medicine. Medicaid is socialized medicine. Healthcare for vets is socialized medicine. As someone on medicare I can attest to the fact that it’s a great system, though it certainly has problems. I had far more problems, however, when I was dependent upon profit-motivated companies to provide me with health insurance. I have absolutely nothing against profit-motivated companies, especially as I’m a business owner myself. They just aren’t a very good solution to providing coverage when the demand for healthcare has a very low level of elasticity. We need to stop thinking in terms that create knee-jerk reactions and start thinking about what works best.

Road construction and maintenance, railroad systems, law enforcement, fire protection and many. many other services are socialism, too. So is the U.S. system of tax exempting religious institutions so far as providing fire, police and other public services is concerned. I don’t hear “socialism” opponents protesting that.

“Socialized” medicine is a term only used in the USA. It’s meaningless elsewhere. The USA has an army, a navy, and an airforce, but doesn’t describe these as ‘socialized defence’. We recognise threats to our nation’s health as a threat to our nation. But doctors, drugs companies, medical equipment manufacturers, continue to operate privately and for profit. The UK’s NHS is not socialized. It was ‘nationalised’ during the war when our cities were being bombed. It’s just like defence.

The UK, like most European countries have a degree of private practice – which performs less well than the NHS. The example lower down of a UK patient refused an operation in the US, was a patient expecting the UK to fund care from taxation. There are plenty of examples of US patients refused care by their insurer.

Just curious why we want to place more financial responsibility in the hands of a government that continues to go in debt and can’t guarantee the taxes paid towards Medicare social security will every be available to anyone under the age of 40? To expand government control over already government regulated areas seems insane. Balance budget and reduce national debt before adding more responsibility and money to a incompetent government, regardless of party. If this doesn’t seem sensible, please send me your money and I’ll take care of your money as well as government is now.

The World Health Organization said that Columbia has one of the worst health care systems in the world yet, they ranked them #22 because they had equal access to that terrible system. The USA was ranked number 1 in quality but was ranked #37 because quality only counts 10% toward the rating. Typical of liberal think.

I think you misread that a bit. The US system is ranked 24th, so it’s pretty good but definitely not ranked #1. When you combine that with the fact that we are the most expensive and rank horribly in the accessibility categories, I think 37 is almost generous.

The US health care system is so screwed up it makes it impossible for most people to retire because of the high cost of insurance–even the new Obama care is unaffordable. Third world countries have better health care systems than us. I can only attribute it to the greed of the people who run this country. As said earlier, our government treats health care as a privilege for those who can afford it. Why should we have to “shop” for an insurance that is “best” for us? Why aren’t all of the plans the same, so that no matter what you need to see a doctor for, whether a cold or cancer, the overall cost you pay per month for this service is the same for everyone! That is equality! That is the way health care should be! And don’t give me that socialist crap!

you nailed it Beth. I am a healthcare practitioner and most of my constituients share the exact sediments …kudos

“Third world countries have ‘better’ health care systems than us.” Alright Beth, I challenge you to go have your heart transplant in a third world country if you ever need one.

The WHO rankings are completely devoid of any common sense. Ranking third world countries higher than the US is completely ridiculous. Don’t just believe any biased statistics you hear. Look more closely. Use your brains people.

Why in the world should it be the same across the board? Why should a group of nuns have to pay for birth control/child birth expenses? There is a case going on right now where a nunnary is being charged tens of millions over that. Why should a single (or not) male be responsible for mammograms and other female care? Why should a woman be responsible for a man’s prostate trouble? And why in the world should I be responsible for a smoker’s lung problems or an addict’s treatment?

I extremely disagree with the push for privitisation in my home country of Australia. Many years have gone past where I have had no need for the medical system. The barely noticable standard amount deducted from my income tax to contribute to our countries healthcare is something I’m more than happy to do for my fellow countrymen, regardless of personal usage. Take care of the people around you, simple! I don’t buy into the ploy of ‘I didn’t use this, I don’t do that, so therefor..’ game. In my opinion it has been cunningly exploited by privitisation advocates as justification to leave their brothers and sisters out in the cold. A business has a primary goal to make more money than it did the year before! that and caring for people in need don’t mix too well. The motivations behind systems of care, governance and infrastructure right across the board in most places need to be addressed. Everyone pays their percentage, one that is adequate for research too. By that system the need for profit is taken out of the equation, reducing cost. Medical advancements made in reserched tech. advancements can then also be implemented at cost. With patients not needing insurance approval or lump sums of cash to get what they need to survive or have quality of life, the knock on effects to society and the way we think about caring for others is a step in the right direction we all need.

I’ve been to 77 different countries, experienced (through my work) healthcare offered in at least 20, France, russia, iceland, denmark, australia to name a few, the USA has (b4 obamacare) the absolute, hands down – no completion, most advanced healthcare to offer to it’s poorest citizens. obama care has created what was once a classless system into a class system of healthcare- wait in line, panel decides your procedure to be performed by fewer docs/specialists.

WE’VE BEEN RIPPED OFF

Many doctors are now opting out of socialized medicine in the USA and offering fee for service directly to their patients. This is the only way to save the doctor/patient relationship and the practice of medicine.

The USA does NOT have SOCIALIZED medicine, but according to the rankings the countries that do HAVE socialized medicine are at the top of the list and the US is #37. Where do you live.

Hi Diane,

Socialized medicine is known as Medicare in Canada and Medicare and Medicaid in the United States.

I don’t understand your comment that the government decides the quantity and quality of your healthcare. You are free to go to any doctor you want, as many times as you want. The quality is somewhat regulated – there are very few medical education systems in the world that Canada will accept doctors from without requiring further medical education.

Some provinces restrict how many patients a doctor can see in a day to try to improve care.

So you don’t think that quality should be weighted by access?? So what if a country of 1000 people had all of the worlds best doctors and only 500 people had access to them. 200 people. 5 people!? The others would just die, or go bankrupt getting the proper care.. Access is clearly a HUGELY important variable in the equation – and each country has vastly different rates.

The capitalist approach certainly does stimulate research, but not necessarily for effective cures. Often times it creates marketing for ineffective cures, that the company holds patents on and has the means to promote. Other times it creates ailments and syndromes to fit products it has on the shelf. The mere fact that Cuba,an impoverished nation, ranks very near to the US in effective healthcare, belies the capitalist argument. Politicizing healthcare is it’s biggest impediment.

I think it breaks down to health care for profit. The motivation will always be to improve the bottom line. So the underline story is to supply cheaper healthcare but in reality, it’s simply less coverage.and victims are simply chronic complainers

Genetics should make health care better yet for insurance companies they regard this as a new cash tool. Your genetics will help identify the possible probability of your future health care failure and you will be assessed on these risk also.

Canada’s health care is not perfect but at about 11% of GDP compared to the US at over 18%, better longevity(close to 3 years) and a lot fewer birth deaths. It seems simple decision with just those few stats “longer life, lower cost”

But it is painfully evident to me that the two party system with it’s inability to purge the deadwood has contributed to the polarity we now see.

It is not what is required but simply what is politically feasible or possible. What can be done that will appease the electorate without negatively affecting our fund raising for the next election which is always two years away.

Bad power and mostly greed are killing my southern friends and for the most part, all we can do is watch. If I can make but one humble suggestion in planning the future for next generation: If you want to make America great again consider giving the same reverence to health care and education as you do the second amendment and gun control. And if you don’t believe that look at America after WW2 with the VA, the GI Bill, and the Marshall plan.

Do you have a source of this ranking? Thanks.

Paolla,

This information is available on the World Health Organization’s website at http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/

The ranking is contained in Annex Table 10 available here http://www.who.int/whr/2000/annex/en/index.html

Admin – This is not the source for the data you cite. On the “Annex 10 Table” Canada ranks 30th and the United States is 72nd. There are a variety of tables in the WHO report which rank the countries on different criteria, thus moving the order around. Which table are you citing here, as it is not the “Over All Performance” table. Thanks.

April,

The citation is correct. Perhaps you read the table too quickly.

Hi Admin,

How the HELL is NZ behind America? NZ has GREAT healthcare. We don’t require insurance and we have free care paid for by taxes in emergency situations, or if you need an operation. The only drawback is the waiting time for surgeries but, beyond that, at least we don’t have to pay insurance companies a cent.

America, on the other hand, are slaves to the healthcare system(although I’m looking forward to see what the ACA does).

Looking forward to learning something new,

– Adam

The World Health Organization said that Columbia has one of the worst health care systems in the world yet, they ranked them #22 because they had equal access to that terrible system. The USA was ranked number 1 in quality but was ranked #37 because quality only counts 10% toward the rating. Typical of liberal think.

Andy1555, where do you get your info. The WHO did not say Columbia has one of the worst!! In fact, they have one of the best. I know people from the US that go there specifically for their healthcare. You know little about this, based on your last comment you must be a conservative that falsely believes that the US has the best of everything. Open your eyes, get off your mother’s couch and experience the world.

This is from the year 2000. Anything a little more ‘current’?

Why? Has our system, or any other, changed much? ( dont say ours has, ACa isnt active yet.)

Oh yes it is…..just wait until the employer mandate kicks in January 2015. Talk about all hell breaking loose. Then you will understand that the ACA has very little to do with health care.

Of course everyone thinks they are as or more important than the next guy. We are a fast food society which expects everything now, regardless of how hungry you are. As someone who has experienced both health care systems (the US and Canada) first hand I can tell you, the wait times are not much different. However, in the US if you have private insurance, you will be greeted with open arms like your checking into the Hyatt Regency. In Canada you are greeted with disdain and told to sit down. In the US the floors are shinny buffed with an expensive machine daily using some kind of toxic cleaner and wax. In Canada the floors are dull but clean having been cleaned with some environmentally safe cleaner but without the special polymer based coating. Canadians are mostly treated like cattle. The quality of health care is not much different depending on your condition. The US has centers of excellence which do advanced research and are well funded. In Canada there is advanced research on a much smaller scale. In the US if you don’t have insurance you avoid seeing the doctor unless your on your death bed, in Canada people fill Emergency rooms with relatively minor complaints, or you see you GP on a regular basis. The treatments in Canada are more standard and well tested and endorsed by Health Canada, even stricter then the FDA. As for the so called rationing, it’s not really rationing, it’s prioritizing based on the urgency for treatment, if it can wait it will while the resources are committed to the people who can’t wait. in the US resources are committed to the people who can pay others are directed to free clinics.

This is all true – but only for the wealthy Americans. I’ve been to free clinics, and they are nothing like what you describe here. In Canada, at least everyone has a fair and equal chance to seek treatment. You don’t have to be nobility or a lottery winner to get health care like you do in the U.S.

I have lived in both countries. Received and had relatives receive treatment in both countries. I prefer USA. You pay for treatment there, true. But we pay for it here, too. In taxes.

http://www.fraserinstitute.org/research-news/display.aspx?id=18858

I was neither a lottery winner, nor nobility. I’m just a blue-collar stiff.

When Canadian politicians and bureaucrats leave the country to seek medical care they go to the United States.

When politicians and bureaucrats in the USA seek medical care, they go to the best facilities and doctor’s available. One has to be a very wealthy Canadian to seek care in the USA. Those who have no health insurance in the USA go to ER when they are often in dire situation and would never get a knee replacement if needed. No one in Canada goes without health care.. Everyone gets what they need though elective requires wait.

Mary,

When Canadian politicians leave the country to access free market medicine they go to the USA. Many Canadian patients, who are not wealthy, are forced to leave Canada to access medical care in the USA. Everyone in Canada has government health insurance but not access to medical care. Right now close to 20,000 patients in Saskatchewan are being forced to wait on lists for medically necessary surgery.

Am Canadian and knowthe system … I know people who have needed surgery and did not get it (so they continue in pain) … know people who are suffering while waiting MONTHS just to get an appointment with a specialist … know people who have been on a gurney for days in emergency because there were no rooms available (not exagerated by the way, 3 nights in emergency in the hall way) … People in Canada go without the health care they need all the time! I believe it´s different from province to province … Now living in Mexico, and – based on personal experience – Mexico should be ranked high in the medical facilities and doctors.

This report was published in 2000 with source data from 1997, so the data is now 14 years old. I wonder when they will publish more current rankings and how/if they will differ?

I had a look and see that there has been another World Health Report, published in 2010, but I did not find any world-wide rankings for health systems.

Andrea,

Each of the WHO’s reports covers a specific subject. Their 2010 report is about the financing of health systems. Their next report will cover health research. I’m not sure if or when they will revisit health system performance but you’re right it would be interesting to see how current rankings would compare. Let me know if you come across any current studies or reports covering health system performance.

Will do. Thanks for your response.

Well I say that I had bad experience in Canada or Ontario with the healthcare, it’s free but I have to say it’s not the best. I had to get stiches done and I had to wait for 13 hours to get myself treated by a doctor, and the nurses basically ignored me during that time and told me to sit down. And I basically waited for 13 hours by the doctor. Once I got thru the doctor, he was rude, same as the nurse that was standing by him. Well I got my sitches, but I had to pay for the medication and cruches. Finally I can’t find any family doctor, that I can go reguarly the once a year thing, or if I have some illness I can’t have a family doctor.

Now I’ve been living in Brazil for 3 years now, and we have here two systems the private and public. Now I went thru both, the private I say was excellent no wait times nothing. Doctor treated me with respect and looked after me. Now for the public which people complained about it, well I had a biking accident nothing serious, but had to get also stiches. I was actuall closer to a public place than a private, so I went there. Didn’t have to have any ID just showed up, and as soon as I got there the nurse told me to go to the doctor’s office. I waited there for 2 minutes and the nurse showed up and looked at my knee, well he cleaned it up, and said the doctor will come and see you shortly, 10 minutes later the doctor showed up, and said well we have to give you anesthetic to your knee so we can remove all the small debrees in it, then also stich it up. Well he did it, and after stiching me up he bandaged my knee, and said to go to the other room to get a tetanus shot. He was really friendly, and told me some jokes. Finally on the other room the nurse showed up right away and gave me the shot. And told me to come back tommorow to change the bandage, and I went there for 7 days, to change it and after the 10th day they removed the stiches. I say I was impressed, and I don’t know why people complained about it, and I even told the doctor how it was in Canada, and he just chuckled. Well I know now where I can go and where I don’t have to spend a dime on medicines shots and doctors consultation.

Bruno,

It’s interesting to note that Brazil has both a private and public health care system. Public health care, whether it’s in Canada or Brazil, is not free. At least in Brazil you can exercise your freedom of choice in health care and pay to access medical services in the private system. Thanks for sharing your experiences.

Reverse comparisons, with the US being slow, inattentive and rude but Canada being prompt cheerful and efficient are easily found. This is why statistics matter.

this information is dead wrong… Brazil is on 125 place? How come? They have socialized universal health care and Brazilians never had any problem reaching for doctors or treatment of any kind without being charged for… USA should the on the very bottom of the list, since besides being awfully expensive, they have all the technology but no experience or touch.

I am Brazilian and I have to say you people had great experiences with our health care that do not correspond to the true thing. Indeed we have a universal health care system that is amazing in theory, but does not work how it should.

This list is somewhat BS…….but aside from that….lol……I dont have healthcare, and I live in the U.S.A. …..I go to Canada…….I have healthcare. …….Any questions?……. Something is better than nothing at all.

Taiwan is not a part of the United Nations. The W.H.O. (World Health Organization) only rated members of the U.N.

if saudi arabia is better than jordan, y are all saudis coming to jordan when they can be treated in their country for free.

“Improving the Canadian Healthcare System does not mean we must emulate the American system” thank you for saying this. Canadians have a tendancy to obsessively make comparisons with the U.S., especially on the topic of healthcare. both systems have their flaws, no doubt, but what bothers mw the most about the Canadian system is that you have NO CHOICE in how you are treated. You only have what the government is offering, and it’s often mediocre at best. Canada is supposedly of free country, we have the freedom to purchase whatever house, car, etc we want, but we have NO CHOICE on how our health will be managed. This essentially means that the government owns our bodies and decides how we will be cared for, this is exactly how the soviet union healthcare system was managed. To my knowledge there are only 3 countries in the world where you have no private options of health care: Cuba, North Korea, and Canada!

It is problematic that we are talking about the “Canadian Health Care” system, when in fact there is no such thing. With notable exceptions where health care pertains to First Nations treaty guarantees, the federal government has a very limited involvement in health care.