The meaning of life

The meaning of life

Перевод песни The meaning of life (Offspring, the)

The meaning of life

Смысл жизни

On the way

Trying to get where I’d like to stay

I’m always feeling steered away

By someone trying to tell me

What to say and do.

I don’t want it.

I gotta go find my own way.

I gotta go make my own mistakes.

Sorry man for feeling,

Feeling the way I do.

Oh yeah, oh yeah.

Open wide and they’ll shove in

Their meaning of life.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

But not for me. I’ll do it on my own.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

Open wide and swallow their meaning of life.

I can’t make it work your way.

Thanks but no thanks.

By the way,

I know your path has been tried and so

It may seem like the way to go.

Me, I’d rather be found

Trying something new.

And the bottom line

In all of this seems to say

There’s no right and no wrong way.

Sorry if I don’t feel like

Living the way you do.

Oh yeah, oh yeah.

Open wide and they’ll shove in

Their meaning of life.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

But not for me. I’ll do it on my own.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

Open wide and swallow their meaning of life.

I can’t make it work your way.

Thanks but no thanks.

Oh yeah, oh yeah.

Open wide and they’ll shove in

Their meaning of life.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

But not for me. I’ll do it on my own.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

Open wide and swallow their meaning of life.

I can’t make it work your way.

Thanks but no thanks.

На пути

Пытаясь попасть туда, куда хочу

Я всегда чувствую, что мне пытаются навязать своё мнение

И кто-то пытается сказать мне

Что говорить и делать.

Я не хочу этого

Я хочу найти мой собственный путь.

Хочу совершать мои собственные ошибки.

Извини, парень, за чувство,

Но я это чувствую именно так.

О, да, о, да.

Открой рот пошире и они впихнут тебе

Их смысл жизни.

О, да, о, да

Но не мне. У меня есть свой.

О, да, о, да

Открой рот пошире и проглоти их смысл жизни.

Я не буду делать по-вашему.

Спасибо, но нет, спасибо.

Между прочим

Я знаю, твой путь проверенный и

Он может показаться, как правильный.

Но меня можно застать

За попытками найти что-то новое.

Подводя итог,

Я, наверное, скажу

Тут нет ни правильного ни неправильного пути.

Извини, если мне не нравится

Жить, как ты живешь.

О, да, о, да.

Открой рот пошире и они впихнут тебе

Их смысл жизни.

О, да, о, да

Но не мне. У меня есть свой.

О, да, о, да

Открой рот пошире и проглоти их смысл жизни.

Я не буду делать по-вашему.

Спасибо, но нет, спасибо.

О, да, о, да.

Открой рот пошире и они впихнут тебе

Их смысл жизни.

О, да, о, да

Но не мне. У меня есть свой.

О, да, о, да

Открой рот пошире и проглоти их смысл жизни.

Я не буду делать по-вашему.

Спасибо, но нет, спасибо.

What Is the Meaning of Life? A Guide to Living With Meaning

A wellness advocate who writes about the psychology behind confidence, happiness and well-being. Read full profile

Since the dawn of time, the question, “what is the meaning of life” has captivated humanity’s finest minds. The ultimate goal appears to be to live a meaningful life with purpose.

As diverse as the questions are, the origins of our existence, the reasons humans were “made,” the drive for personal growth, and, of course, religion, are all explored.

There is no shortage of ideas on what the “good life” is all about, what makes us happy and content, and what we can do to achieve it.

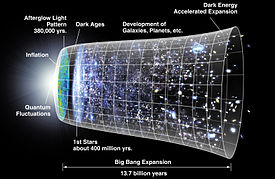

The Big Bang, the beginnings of the cosmos, and the evolution of the species to where we are today will likely be discussed by a researcher if you inquire about the purpose of our existence.

We don’t really need evolution to motivate us and keep us going in the face of adversity, do we? Much more is going on than this. It is our intellect, our self-awareness, and our aspirations, objectives, and aspirations that define who we are as people.

So, if you want to know what life is all about, study Viktor Frankl and Albert Camus, and consider your ideals, progress, community, family, and yes, reproduction, when attempting to answer this question.

Table of Contents

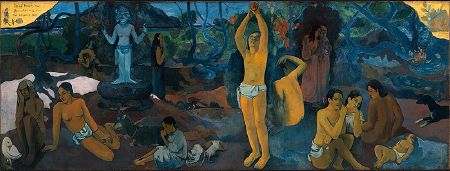

What Is the Meaning of Life — Historical Perspectives

Let’s take a step back and observe what great men throughout history thought a life of purpose to be before we dissect these parts of significance.

The Greeks

Eudaimonia, which means “happiness,” “good life,” or “welfare,” was a belief held by the ancient Greeks. A life lived in eudaimonia was considered the ideal by all of the great Greek philosophers, including Socrates, Thales, Plato, and Aristotle.

“The most difficult thing in life is to know yourself.” – Thales

Self-discovery is the most difficult task in life. In other words, Thales

The meaning of this sentence has been interpreted in a variety of ways. Some people used to believe that gaining virtues was the only way to find meaning in life (such as self-control, courage, wisdom) [1]

According to Aristotle, eudaimonia requires more than a good character; it requires action and excellence. Epicurus, a well-known Greek philosopher, believed that human life should be a time of pleasure and freedom from pain and sorrow.

The Bhagwad Geeta

Ancient India’s texts were written with extraordinary intellectual acumen. The Bhagavad Gita is the most researched, analyzed, and interpreted of all the scriptures. [2]

Our separated material energies are comprised of eight elements: earth, water, fire, air, ether, mind, intellect, and ego.

An ancient Indian text known as the Bhagavad Gita, it is regarded as one of the most important works of Hindu philosophy in both literature and philosophy. Lord or ‘manifested one’: Bhagavad Gita is known as “the song of the Lord or the Lord Himself.”

Mahabharata (the longest Indian epic) incorporated the Bhagavad Gita as a subplot, but it is usually edited separately. The Bhagavad Gita is a section of the Mahabharata that spans 18 short chapters and approximately 700 verses.

Questions like “what is the meaning of life” are at the heart of the Bhagavad Gita. It focuses on how can one lead a spiritually meaningful life without renouncing society. What can a person do to live a moral life if they don’t want to give up their ties to friends and family?

According to popular belief, only ascetics and monks can achieve a perfect spiritual life through renunciation. The Gita, on the other hand, argues that anyone can achieve a perfect spiritual life through active devotion.

Cynicism

Cynicism was founded by Diogenes of Sinope around 380 BC as a way of life and thinking that emphasized virtue and harmony with nature, much like Stoicism later on.

Human reason, according to both schools, is capable of discerning nature’s will; however, their conclusions about what constitutes natural law differed.

The Cynics had a much more primitive view of nature, and so they lived a more solitary life as a result.

While Cynicism sees human institutions like laws and customs as artificial, Stoicism considers them to be part of the fabric of life itself and urges its adherents to uphold them. [3]

When it comes to morality, a Cynic is the antithesis of the idealist.

Diogenes, the founder of Cynicism, is one of the most intriguing characters in all of philosophy. Diogenes lived in a tub and had very little.

To him, human life should be as simple as possible, and he detested much of what “civilization” purports to provide us. A typical quote from him: “Mankind has complicated every simple gift from the gods.”

Rather, people should undergo rigorous training and live in way that is most natural to them. [4]

Stoicism

The Stoic school of thought, founded by Zeno of Citium around 300 B.C., considered the good life to be “living in agreement with nature.” [5]

At that time, people’s principal priority was to avoid a bad life. As a result, they were more likely to structure their thoughts, choices, and actions in a way that enhanced their sense of well-being.

It’s critical to remember that people didn’t always think that acquiring wealth, fame, or other aesthetically pleasing items would bring them happiness. Many people were eager to learn how to cultivate a fine soul.

The Stoics, one of the most well-known schools of thought at the time, presented persuasive answers to problematic concerns like “What do I want out of life?” through their Stoic philosophy. The Stoics proposed a way of life that dealt with the difficulties of being human.

Finally, they said: “I desire enduring enjoyment and peace of mind, which come from being a good person.” This was their ultimate response to all of these difficulties.

As an example, a person can cultivate virtues of character by prioritizing their acts over their words. In other words, if you’re doing things right, you’ll have a better life. And, yes, as you would have suspected, unpleasant behavior led to a more difficult situation.

In essence, Stoicism advocates separating good and evil and doing good while staying calm, focusing on what’s important and under our control, not wasting thoughts on what we can’t change.

Theism

Theists believed in the presence of a deity, or God, who was responsible for the creation of the cosmos. Our lives’ purpose is therefore connected with God’s goal in creating the cosmos, and it is God who gives meaning, purpose, and values to our existence.

This relates to modern-day religious studies and how and why we search for meaning beyond what is readily seen or understood. If you still want to find out answer to the query, what is the true meaning of life? then a deeper understanding of Theism would help.

According to Britannica, Theism is the belief that God is beyond human comprehension, perfect and self-sustaining, but also unusually concerned in the world and its events.

Theists use reasonable reasoning and personal experience to support their belief in God.

Theists often use one of four main kinds of evidence to support their belief in the existence of God: cosmological, ontological, teleological, or moral. The existence of evil must be reconciled with God’s omnipotence and perfection, which are core concepts of theism.

Existentialism

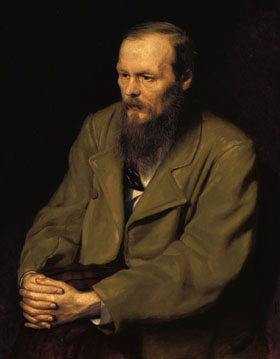

Philosophers like Sren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and Jean-Paul Sartre advocated for this idea of free will in the twentieth century.

“The intuition of free will gives us the truth.” – Corliss Lamont

Rather than relying on society or religion, it is believed that each person creates their own meaning in their own life. Everyone’s reason for being is based on their own circumstances and knowledge. [6]

To put it another way, the meaning of your life is entirely up to you. Simply put, your life’s meaning is what you decide it to be.

What Creates Meaning of Your Life?

Based on the foregoing brief historical tour, it appears that the interpretation of what gives our existence value and purpose changes depending on the historical period and school of thought.

However, there are some unmistakable similarities and repeating themes. Our motivation for assuming a role larger than ourselves, such as serving God’s will or making a contribution to society. At the same time, it’s all nuanced because it’s filtered through our particular prisms, hampered by our historians’ or intellectuals’ beliefs.

Still, there are a few basic types of items that could be ideal candidates for meaning-creators in our lives:

Social

We have an innate urge to connect with others, to be a part of a group, to feel like we belong, and that someone cares about us since we are social creatures.

So, what’s the meaning of life?

Our friendships aren’t the only thing that makes life worthwhile. It’s our parents, siblings, and children. It’s all the people for whom we have feelings of love and affection and who, in turn, have feelings for us.

Achievement

Although pinning our worth only on the results of our efforts can lead to a shaky feeling of self-worth, we nevertheless want our triumphs to outnumber our failures. We want to feel like we’re making progress and achieving our objectives.

“Life is like riding a bicycle, to keep your balance, you must keep moving.” – Albert Einstein

Studies have found that achievements bring greater meaning to our everyday lives. [8]

The pull of the limelight or the desire for accolades will not be enough to justify our existence. What counts is that our efforts be acknowledged, appreciated, and acknowledged. To put it another way, we want our efforts to be meaningful and impactful.

In this podcast from The Lifehack Show, you’ll get a straightforward solution to the question of what personal success looks like:

Competence, Knowledge, and Expertise

The concept of achievement is directly tied to these purpose drivers.

“Life itself is a process of acquiring knowledge.”

Today’s self-improvement movement emphasizes becoming the best at what we do. The Japanese concepts of kaizen and shokunin are among the most well-known examples.

Kaizen is a continuous improvement process that involves learning and building experience in order to improve oneself as a way of life.

Shokunin is a Japanese word that means “craftsman.” It’s also about being proud of what we do and who we are. It’s the desire to improve on a personal and professional level.

Researched Ways That Have Given Meaning to Life (Living Meaning)

However, there are many more colors and understandings of a life well-lived than the three categories that have been mentioned already.

To help you find your own sense of purpose and fulfillment, here are some more ideas.

1. Be Aware of What Makes You Happy and Gives Your Life Meaning

This encompasses your interests, as well as your drive to interact with others, read, write, travel, and keep in shape. Even if these activities do not provide you with any ‘One’ Meaning in Your Life, they have the ability to make you pleased and joyful.

“Be happy for this moment. This moment is your life.” – Omar Khayyam

They are joyous spurs. You might think of them as mini-meanings that, over time, may help you achieve your larger goals and purposes.

However, they will continue to provide you with something to look forward to, a cause to live.

2. What Does Life Mean if Not Embraced By the Love and Existence of a Family?

In order to assure that human life will continue into the foreseeable future, evolutionary biology provides us with the fundamental cause for our existence. Isn’t it all about the survival and continuation of our families? With loved ones, life has a purpose.

“Family is not an important thing. It’s everything.” –Michael J. Fox

When it comes to what makes life worthwhile, having children and family and living it with them is frequently at or near the top of the list. When we feel like we belong, we feel like we can celebrate our triumphs with others.

3. Desire to Leave a Mark in the World

As we come to grips with the fact that our lives are finite, we naturally feel compelled to leave behind something worthwhile. The first step is to focus on one thing that is important to you and build from there.

For example, you could adopt an abandoned puppy and offer it a better existence. You can also help the environment by donating your time to a local food shelter or by beginning to sort your rubbish.

In the words of Mother Teresa:

“We can’t do anything spectacular, but we can do a lot of tiny things with a lot of heart.”

Caring is the key to a fulfilling existence.

4. Be Compassionate and Care About Yourself

What these suggestions imply is that finding methods to take care of ourselves and do things that make us happy is what brings sunshine into our lives.

You don’t need me to tell you that giving and meditation is good for your physical and mental wellbeing; they are widely documented.

Being kind, empathetic, and helpful to others is, in fact, the best way to live a long, healthy life while also reducing our levels of stress and despair.

5. Helping Others Is The Way to Add Meaning to Life

Research participants were asked about their prosocial behavior, life purpose, and level of relationship satisfaction as a way to test this hypothesis.

Prosocial behavior and meaning in life were linked, and relationship satisfaction—in other words, the quality of people’s relationships—accounted for a portion of that link.

According to this article, when we engage in prosocial actions, we fulfill our basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness when we feel good and capable (feeling close to others).

In one study, participants were given the option of giving money to a study participant of their choice, or the researchers simply told them how much money to give.

As long as participants had the option of deciding how much money they wanted to donate, they were more likely to feel satisfied with their psychological needs.

Moreover, that feeling accounted for the link between giving and well-being, which suggests that giving may improve well-being because it helps us meet our psychological needs. ”

Altruism may be especially important for strengthening our relationships and connecting us with others, according to these two studies when taken together, because it meets basic human needs.

“It comes down to this—what are you DOING that’s making a difference?”

We must participate in acts of usefulness—to help and make people happy, to build something—rather than seeking satisfaction and purpose through worldly items.

“The last thing I want is to be on my deathbed and realize there’s zero evidence that I ever existed.”

6. Connect With the World

Another influencer, Alain de Botton, the founder of the famous blog The School of Life, believes that the meaning of life comes down to three activities: [13]

“Some of our most meaningful moments are to do with instances of connection,” he writes, be it to a person, song, or a book, for instance. It takes us out of our isolation. Understanding is our ability to make sense of the world, and service is to work on improving others’ lives.

7. Use the PURE Model

Finally, Peter Wong—a Canadian existential psychologist, has proposed a model known as PURE for individuals to discover meaning in their lives. [14]

There are several options available to you that can provide you with a feeling of purpose. True, you may sometimes feel as if your acts are insignificant as if you are too insignificant to make a difference.

However, this is not the case.

It’s all about bringing out the best in you and doing good for yourself and others when it comes to meaning. As corny as it may seem, if we all commit to the objective of bettering ourselves and the world we live in, a single drop may turn into a wave.

Final Thoughts

Every action we take is influenced by our search for significance in our life. It’s the underlying cause of all of them. There’s no clear answer to the question, either.

There are several ways to establish your purpose, including forming a tribe, striving to be a better version of yourself, helping and serving others, and setting and achieving goals.

Because it’s such a broad term, defining what “purpose” really means might be difficult. It might mean a variety of things to different people.

It’s possible that, in the end, there’s no single, overarching purpose to existence. It’s possible that a mosaic approach to understanding our meaning and purpose is preferable.

Each aspect of our lives—family, friends, accomplishments, recognition—is a piece. To know if you’re satisfied with the picture you’ve created, you have to look at it as a whole.

Or, as Sadhuguru has put it,

“What is life?” I am reminding you that you are life!”

Or, perhaps, it is as Viktor Frankl said:

“The meaning of life is to give life meaning.”

And we are all free to decide for ourselves what, when, and how significant life is.

Перевод песни The meaning of life (Offspring, the)

The meaning of life

Смысл жизни

On the way

Trying to get where I’d like to stay

I’m always feeling steered away

By someone trying to tell me

What to say and do.

I don’t want it.

I gotta go find my own way.

I gotta go make my own mistakes.

Sorry man for feeling,

Feeling the way I do.

Oh yeah, oh yeah.

Open wide and they’ll shove in

Their meaning of life.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

But not for me. I’ll do it on my own.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

Open wide and swallow their meaning of life.

I can’t make it work your way.

Thanks but no thanks.

By the way,

I know your path has been tried and so

It may seem like the way to go.

Me, I’d rather be found

Trying something new.

And the bottom line

In all of this seems to say

There’s no right and no wrong way.

Sorry if I don’t feel like

Living the way you do.

Oh yeah, oh yeah.

Open wide and they’ll shove in

Their meaning of life.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

But not for me. I’ll do it on my own.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

Open wide and swallow their meaning of life.

I can’t make it work your way.

Thanks but no thanks.

Oh yeah, oh yeah.

Open wide and they’ll shove in

Their meaning of life.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

But not for me. I’ll do it on my own.

Oh yeah, oh yeah

Open wide and swallow their meaning of life.

I can’t make it work your way.

Thanks but no thanks.

На пути

Пытаясь попасть туда, куда хочу

Я всегда чувствую, что мне пытаются навязать своё мнение

И кто-то пытается сказать мне

Что говорить и делать.

Я не хочу этого

Я хочу найти мой собственный путь.

Хочу совершать мои собственные ошибки.

Извини, парень, за чувство,

Но я это чувствую именно так.

О, да, о, да.

Открой рот пошире и они впихнут тебе

Их смысл жизни.

О, да, о, да

Но не мне. У меня есть свой.

О, да, о, да

Открой рот пошире и проглоти их смысл жизни.

Я не буду делать по-вашему.

Спасибо, но нет, спасибо.

Между прочим

Я знаю, твой путь проверенный и

Он может показаться, как правильный.

Но меня можно застать

За попытками найти что-то новое.

Подводя итог,

Я, наверное, скажу

Тут нет ни правильного ни неправильного пути.

Извини, если мне не нравится

Жить, как ты живешь.

О, да, о, да.

Открой рот пошире и они впихнут тебе

Их смысл жизни.

О, да, о, да

Но не мне. У меня есть свой.

О, да, о, да

Открой рот пошире и проглоти их смысл жизни.

Я не буду делать по-вашему.

Спасибо, но нет, спасибо.

О, да, о, да.

Открой рот пошире и они впихнут тебе

Их смысл жизни.

О, да, о, да

Но не мне. У меня есть свой.

О, да, о, да

Открой рот пошире и проглоти их смысл жизни.

Я не буду делать по-вашему.

Спасибо, но нет, спасибо.

Meaning of life

The question of the meaning of life is perhaps the most fundamental «why?» in human existence. It relates to the purpose, use, value, and reason for individual existence and that of the universe.

This question has resulted in a wide range of competing answers and explanations, from scientific to philosophical and religious explanations, to explorations in literature. Science, while providing theories about the How and What of life, has been of limited value in answering questions of meaning—the Why of human existence. Philosophy and religion have been of greater relevance, as has literature. Diverse philosophical positions include essentialist, existentialist, skeptic, nihilist, pragmatist, humanist, and atheist. The essentialist position, which states that a purpose is given to our life, usually by a supreme being, closely resembles the viewpoint of the Abrahamic religions.

Contents

While philosophy approaches the question of meaning by reason and reflection, religions approach the question from the perspectives of revelation, enlightenment, and doctrine. Generally, religions have in common two most important teachings regarding the meaning of life: 1) the ethic of the reciprocity of love among fellow humans for the purpose of uniting with a Supreme Being, the provider of that ethic; and 2) spiritual formation towards an afterlife or eternal life as a continuation of physical life.

Scientific Approaches to the Meaning of Life

Science cannot possibly give a direct answer to the question of meaning. There are, strictly speaking, no scientific views on the meaning of biological life other than its observable biological function: to continue. Like a judge confronted with a conflict of interests, the honest scientist will always make the difference between his personal opinions or feelings and the extent to which science can support or undermine these beliefs. That extent is limited to the discovery of ways in which things (including human life) came into being and objectively given, observable laws and patterns that might hint at a certain origin and/or purpose forming the ground for possible meaning.

What is the origin of life?

The question «What is the origin of life?» is addressed in the sciences in the areas of cosmogeny (for the origins of the universe) and abiogenesis (for the origins of biological life). Both of these areas are quite hypothetical—cosmogeny, because no existing physical model can accurately describe the very early universe (the instant of the Big Bang), and abiogenesis, because the environment of the young earth is not known, and because the conditions and chemical processes that may have taken billions of years to produce life cannot (as of yet) be reproduced in a laboratory. It is therefore not surprising that scientists have been tempted to use available data both to support and to oppose the notion that there is a given purpose to the emergence of the cosmos.

What is the nature of life?

Toward answering «What is the nature of life (and of the universe in which we live)?,» scientists have proposed various theories or worldviews over the centuries. They include, but are not limited to, the heliocentric view by Copernicus and Galileo, through the mechanistic clockwork universe of René Descartes and Isaac Newton, to Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, to the quantum mechanics of Heisenberg and Schrödinger in an effort to understand the universe in which we live.

Near the end of the twentieth century, equipped with insights from the gene-centered view of evolution, biologists began to suggest that in so far as there may be a primary function to life, it is the survival of genes. In this approach, success isn’t measured in terms of the survival of species, but one level deeper, in terms of the successful replication of genes over the eons, from one species to the next, and so on. Such positions do not and cannot address the issue of the presence or absence of a purposeful origin, hence meaning.

What is valuable in life?

Science may not be able to tell us what is most valuable in life in a philosophical sense, but some studies bear on related questions. Researchers in positive psychology study factors that lead to life satisfaction (and before them less rigorously in humanistic psychology), in social psychology factors that lead to infants thriving or failing to thrive, and in other areas of psychology questions of motivation, preference, and what people value. Economists have learned a great deal about what is valued in the marketplace; and sociologists examine value at a social level using theoretical constructs such as value theory, norms, anomie, etc.

What is the purpose of, or in, (one’s) life?

Natural scientists look for the purpose of life within the structure and function of life itself. This question also falls upon social scientists to answer. They attempt to do so by studying and explaining the behaviors and interactions of human beings (and every other type of animal as well). Again, science is limited to the search for elements that promote the purpose of a specific life form (individuals and societies), but these findings can only be suggestive when it comes to the overall purpose and meaning.

Analysis of teleology based on science

Teleology is a philosophical and theological study of purpose in nature. Traditional philosophy and Christian theology in particular have always had a strong tendency to affirm teleological positions, based on observation and belief. Since David Hume’s skepticism and Immanuel Kant’s agnostic conclusions in the eighteenth century, the use of teleological considerations to prove the existence of a purpose, hence a purposeful creator of the universe, has been seriously challenged. Purpose-oriented thinking is a natural human tendency which Kant already acknowledged, but that does not make it legitimate as a scientific explanation of things. In other words, teleology can be accused of amounting to wishful thinking.

The alleged «debunking» of teleology in science received a fresh impetus from advances in biological knowledge such as the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (i.e., natural selection). Best-selling author and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins puts forward his explanation based on such findings. Ironically, it is also science that has recently given a new impetus to teleological thinking by providing data strongly suggesting the impossibility of random development in the creation of the universe and the appearance of life (e.g., the «anthropic principle»).

Philosophy of the Meaning of Life

While scientific approaches to the meaning of life aim to describe relevant empirical facts about human existence, philosophers are concerned about the relationship between ideas such as the proper interpretation of empirical data. Philosophers have considered such questions as: «Is the question ‘What is the meaning of life?’ a meaningful question?»; «What does it really mean?»; and «If there are no objective values, then is life meaningless?» Some philosophical disciplines have also aimed to develop an understanding of life that explains, regardless of how we came to be here, what we should do, now that we are here.

Since the question about life’s meaning inevitably leads to the question of a possible divine origin to life, philosophy and theology are inextricably linked on this issue. Whether the answer to the question about a divine creator is yes, no, or «not applicable,» the question will come up. Nevertheless, philosophy and religion significantly differ in much of their approach to the question. Hence, they will be treated separately.

Essentialist views

Essentialist views generally start with the assumption that there is a common essence in human beings, human nature, and that this nature is the starting point for any evaluation of the meaning of life. In classic philosophy, from Plato’s idealism to Descartes’ rationalism, humans have been seen as rational beings or «rational animals.» Conforming to that inborn quality is then seen as the aim of life.

Reason, in that context, also has a strong value-oriented and ethical connotation. Philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, and many others had views about what sort of life is best (and hence most meaningful). Aristotle believed that the pursuit of happiness is the Highest Good, and that such is achievable through our uniquely human capacity to reason. The notion of the highest good as the rational aim in life can still be found in later thinkers like Kant. A strong ethical connotation can be found in the Ancient Stoics, while Epicureanism saw the meaning of life in the search for the highest pleasure or happiness.

All these views have in common the assumption that it is possible to discover, and then practice, whatever is seen as the highest good through rational insight, hence the term «philosophy»—the love of wisdom. With Plato, the wisdom to discover the true meaning of life is found in connection with the notion of the immortal soul that completes its course in earthly life once it liberates itself from the futile earthly goals. In this, Plato prefigures a theme that would be essential in Christianity, that of God-given eternal life, as well as the notion that the soul is good and the flesh evil or at least a hindrance to the fulfillment of one’s true goal. At the same time, the concept that one has to rise above deceptive appearances to reach a proper understanding of life’s meaning has links to Eastern and Far Eastern traditions.

In medieval and modern philosophy, the Platonic and Aristotelian views were incorporated in a worldview centered on the theistic concept of the Will of God as the determinant factor for the meaning of our life, which was then seen as achieving moral perfection in ways pleasing to God. Modern philosophy came to experience considerable struggle in its attempt to make this view compatible with the rational discourse of a philosophy free of any prejudice. With Kant, the given of a God and his will fell away as a possible rational certainty. Certainty concerning purpose and meaning were moved from God to the immediacy of consciousness and conscience, as epitomized in Kant’s teaching of the categorical imperative. This development would gradually lead to the later supremacy of an existentialist discussion of the meaning of life, since such a position starts with the self and its choices, rather than with a purpose given «from above.»

The emphasis on meaning as destiny, rather than choice, would one more time flourish in the early nineteenth century’s German Idealism, notably in the philosophy of Hegel where the overall purpose of history is seen as the embodiment of the Absolute Spirit in human society.

Existentialist views

Existentialist views concerning the meaning of life are based on the idea that it is only personal choices and commitments that can give any meaning to life since, for an individual, life can only be his or her life, and not an abstractly given entity. By going this route, existentialist thinkers seek to avoid the trappings of dogmatism and pursue a more genuine route. That road, however, is inevitably filled with doubt and hesitation. With the refusal of committing oneself to an externally given ideal comes the limitation of certainty to that alone which one chooses.

Presenting essentialism and existentialism as strictly divided currents would undoubtedly amount to a caricature, hence such a distinction can only be seen as defining a general trend. It is very clear, however, that philosophical thought from the mid-nineteenth century on has been strongly marked by the influence of existentialism. At the same time, the motives of dread, loss, uncertainty, and anguish in the face of an existence that needs to be constructed “out of nothing” have become predominant. These developments also need to be studied in the context of modern and contemporary historical events leading to the World Wars.

A universal existential contact with the question of meaning is found in situations of extreme distress, where all expected goals and purposes are shattered, including one’s most cherished hopes and convictions. The individual is then left with the burning question whether there still remains an even more fundamental, self-transcending meaning to existence. In many instances, such existential crises have been the starting point for a qualitative transformation of one’s perceptions.

Søren Kierkegaard invented the term «leap of faith» and argued that life is full of absurdity and the individual must make his or her own values in an indifferent world. For Kierkegaard, an individual can have a meaningful life (or at least one free of despair) if the individual relates the self in an unconditional commitment despite the inherent vulnerability of doing so in the midst our doubt. Genuine meaning is thus possible once the individual reaches the third, or religious, stage of life. Kirkegaard’s sincere commitment, far remote from any ivory tower philosophy, brings him into close contact with religious-philosophical approaches in the Far East, such as that of Buddhism, where the attainment of true meaning in life is only possible when the individual passes through several stages before reaching enlightenment that is fulfillment in itself, without any guarantee given from the outside (such as the certainty of salvation).

Although not generally categorized as an existentialist philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer offered his own bleak answer to «what is the meaning of life?» by determining one’s visible life as the reflection of one’s will and the Will (and thus life) as being an aimless, irrational, and painful drive. The essence of reality is thus seen by Schopenhauer as totally negative, the only promise of salvation, deliverance, or at least escape from suffering being found in world-denying existential attitudes such as aesthetic contemplation, sympathy for others, and asceticism.

Twentieth-century thinkers like Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre are representative of a more extreme form of existentialism where the existential approach takes place within the framework of atheism, rather than Christianity. Gabriel Marcel, on the other hand, is an example of Christian existentialism. For Paul Tillich, the meaning of life is given by one’s inevitable pursuit of some ultimate concern, whether it takes on the traditional form of religion or not. Existentialism is thus an orientation of the mind that can be filled with the greatest variety of content, leading to vastly different conclusions.

Skeptical and nihilist views

Skepticism has always been a strong undercurrent in the history of thought, as uncertainty about meaning and purpose has always existed even in the context of the strongest commitment to a certain view. Skepticism can also be called an everyday existential reality for every human being, alongside whatever commitments or certainties there may be. To some, it takes on the role of doubt to be overcome or endured. To others, it leads to a negative conclusion concerning our possibility of making any credible claim about the meaning of our life.

Skepticism in philosophy has existed since antiquity where it formed several schools of thought in Greece and in Rome. Until recent times, however, overt skepticism has remained a minority position. With the collapse of traditional certainties, skepticism has become increasingly prominent in social and cultural life. Ironically, because of its very nature of denying the possibility of certain knowledge, it is not a position that has produced major thinkers, at least not in its pure form.

The philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein and logical positivism, as well as the whole tradition of analytical philosophy represent a particular form of skepticism in that they challenge the very meaningfulness of questions like «the meaning of life,» questions that do not involve verifiable statements.

Whereas skepticism denies the possibility of certain knowledge and thus rejects any affirmative statement about the meaning of life, nihilism amounts to a flat denial of such meaning or value. Friedrich Nietzsche characterized nihilism as emptying the world and especially human existence of meaning, purpose, comprehensible truth, or essential value. The term nihilism itself comes from the Latin nihil, which means «nothing.»

Nihilism thus explores the notion of existence without meaning. Though nihilism tends toward defeatism, one can find strength and reason for celebration in the varied and unique human relationships it explores. From a nihilist point of view, morals are valueless and only hold a place in society as false ideals created by various forces. The characteristic that distinguishes nihilism from other skeptical or relativist philosophies is that, rather than merely insisting that values are subjective or even unwarranted, nihilism declares that nothing is of value, as the name implies.

Pragmatist views

Pragmatic philosophers suggest that rather than a truth about life, we should seek a useful understanding of life. William James argued that truth could be made but not sought. Thus, the meaning of life is a belief about the purpose of life that does not contradict one’s experience of a purposeful life. Roughly, this could be applied as: «The meaning of life is those purposes which cause you to value it.» To a pragmatist, the meaning of life, your life, can be discovered only through experience.

Pragmatism is a school of philosophy which originated in the United States in the late 1800s. Pragmatism is characterized by the insistence on consequences, utility and practicality as vital components of truth. Pragmatism objects to the view that human concepts and intellect represent reality, and therefore stands in opposition to both formalist and rationalist schools of philosophy. Rather, pragmatism holds that it is only in the struggle of intelligent organisms with the surrounding environment that theories and data acquire significance. Pragmatism does not hold, however, that just anything that is useful or practical should be regarded as true, or anything that helps us to survive merely in the short-term; pragmatists argue that what should be taken as true is that which most contributes to the most human good over the longest course. In practice, this means that for pragmatists, theoretical claims should be tied to verification practices—i.e., that one should be able to make predictions and test them—and that ultimately the needs of humankind should guide the path of human inquiry.

Humanistic views

Human purpose is determined by humans, completely without supernatural influence. Nor does knowledge come from supernatural sources, it flows from human observation, experimentation, and rational analysis preferably utilizing the scientific method: the nature of the universe is what we discern it to be. As are ethical values, which are derived from human needs and interests as tested by experience.

Enlightened self-interest is at the core of humanism. The most significant thing in life is the human being, and by extension, the human race and the environment in which we live. The happiness of the individual is inextricably linked to the well-being of humanity as a whole, in part because we are social animals which find meaning in relationships, and because cultural progress benefits everybody who lives in that culture.

When the world improves, life in general improves, so, while the individual desires to live well and fully, humanists feel it is important to do so in a way that will enhance the well-being of all. While the evolution of the human species is still (for the most part) a function of nature, the evolution of humanity is in our hands and it is our responsibility to progress it toward its highest ideals. In the same way, humanism itself is evolving, because humanists recognize that values and ideals, and therefore the meaning of life, are subject to change as our understanding improves.

The doctrine of humanism is set forth in the «Humanist Manifesto» and «A Secular Humanist Declaration.»

Atheistic views

Atheism in its strictest sense means the belief that no God or Supreme Being (of any type or number) exists, and by extension that neither the universe nor its inhabitants were created by such a Being. Because atheists reject supernatural explanations for the existence of life, lacking a deistic source, they commonly point to blind abiogenesis as the most likely source for the origin of life. As for the purpose of life, there is no one particular atheistic view. Some atheists argue that since there are no gods to tell us what to value, we are left to decide for ourselves. Other atheists argue that some sort of meaning can be intrinsic to life itself, so the existence or non-existence of God is irrelevant to the question (a version of Socrates’ Euthyphro dilemma). Some believe that life is nothing more than a byproduct of insensate natural forces and has no underlying meaning or grand purpose. Other atheists are indifferent towards the question, believing that talking about meaning without specifying «meaning to whom» is an incoherent or incomplete thought (this can also fit with the idea of choosing the meaning of life for oneself).

Religious Approaches to the Meaning of Life

The religious traditions of the world have offered their own doctrinal responses to the question about life’s meaning. These answers also remain independently as core statements based on the claim to be the product of revelation or enlightenment, rather than human reflection.

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

Judaism regards life as a precious gift from God; precious not only because it is a gift from God, but because, for humans, there is a uniqueness attached to that gift. Of all the creatures on Earth, humans are created in the image of God. Our lives are sacred and precious because we carry within us the divine image, and with it, unlimited potential.

While Judaism teaches about elevating yourself in spirituality, connecting to God, it also teaches that you are to love your neighbor: «Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against one of your people, but love your neighbor as yourself» (Leviticus 19:18). We are to practice it in this world Olam Hazeh to prepare ourselves for Olam Haba (the world to come).

Kabbalah takes it one step further. The Zohar states that the reason for life is to better one’s soul. The soul descends to this world and endures the trials of this life, so that it can reach a higher spiritual state upon its return to the source.

Christianity

Christians draw many of their beliefs from the Bible, and believe that loving God and one’s neighbor is the meaning of life. In order to achieve this, one would ask God for the forgiveness of one’s own sins, and one would also forgive the sins of one’s fellow humans. By forgiving and loving one’s neighbor, one can receive God into one’s heart: «But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. Then your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, because he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked» (Luke 6:35). Christianity believes in an eternal afterlife, and declares that it is an unearned gift from God through the love of Jesus Christ, which is to be received or forfeited by faith (Ephesians 2:8-9; Romans 6:23; John 3:16-21; 3:36).

Christians believe they are being tested and purified so that they may have a place of responsibility with Jesus in the eternal Kingdom to come. What the Christian does in this life will determine his place of responsibility with Jesus in the eternal Kingdom to come. Jesus encouraged Christians to be overcomers, so that they might share in the glorious reign with him in the life to come: «To him who overcomes, I will give the right to sit with me on my throne, just as I overcame and sat down with my Father on his throne» (Revelation 3:21).

The Bible states that it is God «in whom we live and move and have our being» (Acts 17:28), and that to fear God is the beginning of wisdom, and to depart from evil is the beginning of understanding (Job 28:28). The Bible also says, «Whether therefore ye eat, or drink, or whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God» (1 Corinthians 10:31).

Islam

In Islam the ultimate objective of man is to seek the pleasure of Allah by living in accordance with the divine guidelines as stated in the Qur’an and the tradition of the Prophet. The Qur’an clearly states that the whole purpose behind the creation of man is for glorifying and worshipping Allah: «I only created jinn and man to worship Me» (Qur’an 51:56). Worshiping in Islam means to testify to the oneness of God in his lordship, names and attributes. Part of the divine guidelines, however, is almsgiving (zakat), one of the Five Pillars of Islam. Also regarding the ethic of reciprocity among fellow humans, the Prophet teaches that «None of you [truly] believes until he wishes for his brother what he wishes for himself.» [1] To Muslims, life was created as a test, and how well one performs on this test will determine whether one finds a final home in Jannah (Heaven) or Jahannam (Hell).

The esoteric Muslim view, generally held by Sufis, the universe exists only for God’s pleasure.

South Asian religions

Hinduism

For Hindus, the purpose of life is described by the purusharthas, the four ends of human life. These goals are, from lowest to highest importance: Kāma (sensual pleasure or love), Artha (wealth), Dharma (righteousness or morality) and Moksha (liberation from the cycle of reincarnation). Dharma connotes general moral and ethical ideas such as honesty, responsibility, respect, and care for others, which people fulfill in the course of life as a householder and contributing member of society. Those who renounce home and career practice a life of meditation and austerities to reach Moksha.

Hinduism is an extremely diverse religion. Most Hindus believe that the spirit or soul—the true «self» of every person, called the ātman—is eternal. According to the monistic/pantheistic theologies of Hinduism (such as the Advaita Vedanta school), the ātman is ultimately indistinct from Brahman, the supreme spirit. Brahman is described as «The One Without a Second»; hence these schools are called «non-dualist.» The goal of life according to the Advaita school is to realize that one’s ātman (soul) is identical to Brahman, the supreme soul. The Upanishads state that whoever becomes fully aware of the ātman as the innermost core of one’s own self, realizes their identity with Brahman and thereby reaches Moksha (liberation or freedom). [2]

Other Hindu schools, such as the dualist Dvaita Vedanta and other bhakti schools, understand Brahman as a Supreme Being who possesses personality. On these conceptions, the ātman is dependent on Brahman, and the meaning of life is to achieve Moksha through love towards God and on God’s grace.

Whether non-dualist (Advaita) or dualist (Dvaita), the bottom line is the idea that all humans are deeply interconnected with one another through the unity of the ātman and Brahman, and therefore, that they are not to injure one another but to care for one another.

Jainism

Jainism teaches that every human is responsible for his or her actions. The Jain view of karma is that every action, every word, every thought produces, besides its visible, an invisible, transcendental effect on the soul. The ethical system of Jainism promotes self-discipline above all else. By following the ascetic teachings of the Tirthankara or Jina, the 24 enlightened spiritual masters, a human can reach a point of enlightenment, where he or she attains infinite knowledge and is delivered from the cycle of reincarnation beyond the yoke of karma. That state is called Siddhashila. Although Jainism does not teach the existence of God(s), the ascetic teachings of the Tirthankara are highly developed regarding right faith, right knowledge, and right conduct. The meaning of life consists in achievement of complete enlightenment and bliss in Siddhashila by practicing them.

Jains also believe that all living beings have an eternal soul, jīva, and that all souls are equal because they all possess the potential of being liberated. So, Jainism includes strict adherence to ahimsa (or ahinsā), a form of nonviolence that goes far beyond vegetarianism. Food obtained with unnecessary cruelty is refused. Hence the universal ethic of reciprocity in Jainism: «Just as pain is not agreeable to you, it is so with others. Knowing this principle of equality treat other with respect and compassion» (Saman Suttam 150).

Buddhism

One of the central views in Buddhism is a nondual worldview, in which subject and object are the same, and the sense of doer-ship is illusionary. On this account, the meaning of life is to become enlightened as to the nature and oneness of the universe. According to the scriptures, the Buddha taught that in life there exists dukkha, which is in essence sorrow/suffering, that is caused by desire and it can be brought to cessation by following the Noble Eightfold Path. This teaching is called the Catvāry Āryasatyāni (Pali: Cattāri Ariyasaccāni ), or the «Four Noble Truths»:

Theravada Buddhism promotes the concept of Vibhajjavada (literally, «teaching of analysis»). This doctrine says that insight must come from the aspirant’s experience, critical investigation, and reasoning instead of by blind faith; however, the scriptures of the Theravadin tradition also emphasize heeding the advice of the wise, considering such advice and evaluation of one’s own experiences to be the two tests by which practices should be judged. The Theravadin goal is liberation (or freedom) from suffering, according to the Four Noble Truths. This is attained in the achievement of Nirvana, which also ends the repeated cycle of birth, old age, sickness and death.

Mahayana Buddhist schools de-emphasize the traditional Theravada ideal of the release from individual suffering (dukkha) and attainment of awakening (Nirvana). In Mahayana, the Buddha is seen as an eternal, immutable, inconceivable, omnipresent being. The fundamental principles of Mahayana doctrine are based around the possibility of universal liberation from suffering for all beings, and the existence of the transcendent Buddha-nature, which is the eternal Buddha essence present, but hidden and unrecognized, in all living beings. Important part of the Buddha-nature is compassion.

Buddha himself talks about the ethic of reciprocity: «One who, while himself seeking happiness, oppresses with violence other beings who also desire happiness, will not attain happiness hereafter.» (Dhammapada 10:131). [3]

Sikhism

Sikhism sees life as an opportunity to understand God the Creator as well as to discover the divinity which lies in each individual. God is omnipresent (sarav viāpak) in all creation and visible everywhere to the spiritually awakened. Guru Nanak Dev stresses that God must be seen from «the inward eye,» or the «heart,» of a human being: devotees must meditate to progress towards enlightenment. In this context of the omnipresence of God, humans are to love one another, and they are not enemies to one another.

East Asian religions

Confucianism

Confucianism places the meaning of life in the context of human relationships. People’s character is formed in the given relationships to their parents, siblings, spouse, friends and social roles. There is need for discipline and education to learn the ways of harmony and success within these social contexts. The purpose of life, then, is to fulfill one’s role in society, by showing honesty, propriety, politeness, filial piety, loyalty, humaneness, benevolence, etc. in accordance with the order in the cosmos manifested by Tian (Heaven).

Confucianism deemphasizes afterlife. Even after humans pass away, they are connected with their descendants in this world through rituals deeply rooted in the virtue of filial piety that closely links different generations. The emphasis is on normal living in this world, according to the contemporary scholar of Confucianism Wei-Ming Tu, «We can realize the ultimate meaning of life in ordinary human existence.» [4]

Daoism

The Daoist cosmogony emphasizes the need for all humans and all sentient beings to return to the primordial or to rejoin with the Oneness of the Universe by way of self-correction and self realization. It is the objective for all adherents to understand and be in tune with the Dao (Way) of nature’s ebb and flow.

Within the theology of Daoism, originally all humans were beings called yuanling («original spirits») from Taiji and Tao, and the meaning in life for the adherents is to realize the temporal nature of their existence, and all adherents are expected to practice, hone and conduct their mortal lives by way of Xiuzhen (practice of the truth) and Xiushen (betterment of the self), as a preparation for spiritual transcendence here and hereafter.

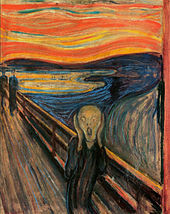

The Meaning of Life in Literature

Insight into the meaning of life has been a central preoccupation of literature from ancient times. Beginning with Homer through such twentieth-century writers as Franz Kafka, authors have explored ultimate meaning through usually indirect, «representative» depictions of life. For the ancients, human life appeared within the matrix of a cosmological order. In the dramatic saga of war in Homer’s Illiad, or the great human tragedies of Greek playwrights such as Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides, inexorable Fate and the machinations of the Gods are seen as overmastering the feeble means of mortals to direct their destiny.

In the Middle Ages, Dante grounded his epic Divine Comedy in an explicitly Christian context, with meaning derived from moral discernment based on the immutable laws of God. The Renaissance humanists Miguel de Cervantes and William Shakespeare influenced much later literature by more realistically portraying human life and beginning an enduring literary tradition of elevating human experience as the grounds upon which meaning may be discerned. With notable exceptions—such as satirists such as François-Marie Voltaire and Jonathan Swift, and explicitly Christian writers such as John Milton—Western literature began to examine human experience for clues to ultimate meaning. Literature became a methodology to explore meaning and to represent truth by holding up a mirror to human life.

In the nineteenth century Honoré de Balzac, considered one of the founders of literary realism, explored French society and studied human psychology in a massive series of novels and plays he collectively titled The Human Comedy. Gustave Flaubert, like Balzac, sought to realistically analyze French life and manners without imposing preconceived values upon his object of study.

Novelist Herman Melville used the quest for the White Whale in Moby-Dick not only as an explicit symbol of his quest for the truth but as a device to discover that truth. The literary method became for Melville a process of philosophic inquiry into meaning. Henry James made explicit this important role in «The Art of Fiction» when he compared the novel to fine art and insisted that the novelist’s role was exactly analogous to that of the artist or philosopher:

Realistic novelists such as Leo Tolstoy and especially Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote «novels of ideas,» recreating Russian society of the late nineteenth century with exacting verisimilitude, but also introducing characters who articulated essential questions concerning the meaning of life. These questions merged into the dramatic plot line in such novels as Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov. In the twentieth century Thomas Mann labored to grasp the calamity of the First World War in his philosophical novel The Magic Mountain. Franz Kafka, Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Samuel Beckett, and other existential writers explored in literature a world where tradition, faith, and moral certitude had collapsed, leaving a void. Existential writers preeminently addressed questions of the meaning of life through studying the pain, anomie, and psychological dislocation of their fictional protagonists. In Kafka’s Metamorphosis, to take a well known example, an office functionary wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a giant cockroach, a new fact he industriously labors to incorporate into his routine affairs.

The concept of life having a meaning has been both parodied and promulgated, usually indirectly, in popular culture as well. For example, at the end of Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life, a character is handed an envelope wherein the meaning of life is spelled out: «Well, it’s nothing very special. Uh, try to be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try to live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations.» Such tongue-in-cheek representations of meaning are less common than film and television presentations that locate the meaning of life in the subjective experience of the individual. This popular post-modern notion generally enables the individual to discover meaning to suit his or her inclinations, marginalizing what are presumed to be dated values, while somewhat inconsistently incorporating the notion of the relativity of values into an absolute principle.

Assessment

Probably the most universal teachings concerning the meaning of life, to be followed in virtually all religions in spite of much diversity of their traditions and positions, are: 1) the ethic of reciprocity among fellow humans, the «Golden Rule,» derived from an ultimate being, called God, Allah, Brahman, Taiji, or Tian; and 2) the spiritual dimension of life including an afterlife or eternal life, based on the requirement not to indulge in the external and material aspect of life. Usually, the connection of the two is that the ethic of reciprocity is a preparation in this world for the elevation of spirituality and for afterlife. It is important to note that these two constitutive elements of any religious view of meaning are common to all religious and spiritual traditions, although Jainism’s ethical teachings may not be based on any ultimate divine being and the Confucianist theory of the continual existence of ancestors together with descendants may not consider afterlife in the sense of being the other world. These two universal elements of religions are acceptable also to religious literature, the essentialist position in philosophy, and in some way to some of the existentialist position.

Scientific theories can be used to support these two elements, depending upon whether one’s perspective is religious or not. For example, the biological function of survival and continuation can be used in support of the religious doctrine of eternal life, and modern physics can be considered not to preclude some spiritual dimension of the universe. Also, when science observes the reciprocity of orderly relatedness, rather than random development, in the universe, it can support the ethic of reciprocity in the Golden Rule. Of course, if one’s perspective is not religious, then science may not be considered to support religion. Recently, however, the use of science in support of religious claims has greatly increased, and it is evidenced by the publication of many books and articles on the relationship of science and religion. The importance of scientific investigations on the origin and nature of life, and of the universe in which we live, has been increasingly recognized, because the question on the meaning of life has been acknowledged to need more than religious answers, which, without scientific support, are feared to sound irrelevant and obsolete in the age of science and technology. Thus, religion is being forced to take into account the data and systematic answers provided by science. Conversely, the role of religion has become that of offering a meaningful explanation of possible solutions suggested by science.

It is interesting to observe that humanists, who usually deny the existence of God and of afterlife, believe that it is important for all humans to love and respect one another: «Humanists acknowledge human interdependence, the need for mutual respect and the kinship of all humanity.» [6] Also, much of secular literature, even without imposing preconceived values, describes the beauty of love and respect in the midst of hatred and chaos in human life. Also, even a common sense discussion on the meaning of life can argue for the existence of eternal life, for the notion of self-destruction at one’s death would appear to make the meaning of life destroyed along with life itself. Thus, the two universal elements of religions seem not to be totally alien to us.

Christian theologian Millard J. Erickson sees God’s blessing for humans to be fruitful, multiply, and have dominion over the earth (Genesis 1:28) as «the purpose or reason for the creation of humankind.» [7] This biblical account seems to refer to the ethical aspect of the meaning of life, which is the reciprocal relationship of love involving multiplied humanity and all creation centering on God, although, seen with secular eyes, it might be rather difficult to accept the ideal of such a God-given purpose or meaning of life based on simple observation of the world situation.

Notes

References

External links

All links retrieved June 28, 2021.

General Philosophy Sources

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

The Meaning of Life

Many major historical figures in philosophy have provided an answer to the question of what, if anything, makes life meaningful, although they typically have not put it in these terms (with such talk having arisen only in the past 250 years or so, on which see Landau 1997). Consider, for instance, Aristotle on the human function, Aquinas on the beatific vision, and Kant on the highest good. Relatedly, think about Koheleth, the presumed author of the Biblical book Ecclesiastes, describing life as “futility” and akin to “the pursuit of wind,” Nietzsche on nihilism, as well as Schopenhauer when he remarks that whenever we reach a goal we have longed for we discover “how vain and empty it is.” While these concepts have some bearing on happiness and virtue (and their opposites), they are straightforwardly construed (roughly) as accounts of which higher-order final ends, if any, a person ought to realize that would make her life significant.

Despite the venerable pedigree, it is only since the 1980s or so that a distinct field of the meaning of life has been established in Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy, on which this survey focuses, and it is only in the past 20 years that debate with real depth and intricacy has appeared. Two decades ago analytic reflection on life’s meaning was described as a “backwater” compared to that on well-being or good character, and it was possible to cite nearly all the literature in a given critical discussion of the field (Metz 2002). Neither is true any longer. Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy of life’s meaning has become vibrant, such that there is now way too much literature to be able to cite comprehensively in this survey. To obtain focus, it tends to discuss books, influential essays, and more recent works, and it leaves aside contributions from other philosophical traditions (such as the Continental or African) and from non-philosophical fields (e.g., psychology or literature). This survey’s central aim is to acquaint the reader with current analytic approaches to life’s meaning, sketching major debates and pointing out neglected topics that merit further consideration.

When the topic of the meaning of life comes up, people tend to pose one of three questions: “What are you talking about?”, “What is the meaning of life?”, and “Is life in fact meaningful?”. The analytic literature can be usefully organized according to which question it seeks to answer. This survey starts off with recent work that addresses the first, abstract (or “meta”) question regarding the sense of talk of “life’s meaning,” i.e., that aims to clarify what we have in mind when inquiring into the meaning of life (section 1). Afterward, it considers texts that provide answers to the more substantive question about the nature of meaningfulness (sections 2–3). There is in the making a sub-field of applied meaning that parallels applied ethics, in which meaningfulness is considered in the context of particular cases or specific themes. Examples include downshifting (Levy 2005), implementing genetic enhancements (Agar 2013), making achievements (Bradford 2015), getting an education (Schinkel et al. 2015), interacting with research participants (Olson 2016), automating labor (Danaher 2017), and creating children (Ferracioli 2018). In contrast, this survey focuses nearly exclusively on contemporary normative-theoretical approaches to life’s meanining, that is, attempts to capture in a single, general principle all the variegated conditions that could confer meaning on life. Finally, this survey examines fresh arguments for the nihilist view that the conditions necessary for a meaningful life do not obtain for any of us, i.e., that all our lives are meaningless (section 4).

1. The Meaning of “Meaning”

One part of philosophy of life’s meaning consists of the systematic attempt to identify what people have in mind when they think about the topic or what they mean by talk of “life’s meaning.” For many in the field, terms such as “importance” and “significance” are synonyms of “meaningfulness” and so are insufficiently revealing, but there are those who draw a distinction between meaningfulness and significance (Singer 1996, 112–18; Belliotti 2019, 145–50, 186). There is also debate about how the concept of a meaningless life relates to the ideas of a life that is absurd (Nagel 1970, 1986, 214–23; Feinberg 1980; Belliotti 2019), futile (Trisel 2002), and not worth living (Landau 2017, 12–15; Matheson 2017).

A useful way to begin to get clear about what thinking about life’s meaning involves is to specify the bearer. Which life does the inquirer have in mind? A standard distinction to draw is between the meaning “in” life, where a human person is what can exhibit meaning, and the meaning “of” life in a narrow sense, where the human species as a whole is what can be meaningful or not. There has also been a bit of recent consideration of whether animals or human infants can have meaning in their lives, with most rejecting that possibility (e.g., Wong 2008, 131, 147; Fischer 2019, 1–24), but a handful of others beginning to make a case for it (Purves and Delon 2018; Thomas 2018). Also under-explored is the issue of whether groups, such as a people or an organization, can be bearers of meaning, and, if so, under what conditions.

Most analytic philosophers have been interested in meaning in life, that is, in the meaningfulness that a person’s life could exhibit, with comparatively few these days addressing the meaning of life in the narrow sense. Even those who believe that God is or would be central to life’s meaning have lately addressed how an individual’s life might be meaningful in virtue of God more often than how the human race might be. Although some have argued that the meaningfulness of human life as such merits inquiry to no less a degree (if not more) than the meaning in a life (Seachris 2013; Tartaglia 2015; cf. Trisel 2016), a large majority of the field has instead been interested in whether their lives as individual persons (and the lives of those they care about) are meaningful and how they could become more so.

Focusing on meaning in life, it is quite common to maintain that it is conceptually something good for its own sake or, relatedly, something that provides a basic reason for action (on which see Visak 2017). There are a few who have recently suggested otherwise, maintaining that there can be neutral or even undesirable kinds of meaning in a person’s life (e.g., Mawson 2016, 90, 193; Thomas 2018, 291, 294). However, these are outliers, with most analytic philosophers, and presumably laypeople, instead wanting to know when an individual’s life exhibits a certain kind of final value (or non-instrumental reason for action).

Another claim about which there is substantial consensus is that meaningfulness is not all or nothing and instead comes in degrees, such that some periods of life are more meaningful than others and that some lives as a whole are more meaningful than others. Note that one can coherently hold the view that some people’s lives are less meaningful (or even in a certain sense less “important”) than others, or are even meaningless (unimportant), and still maintain that people have an equal standing from a moral point of view. Consider a consequentialist moral principle according to which each individual counts for one in virtue of having a capacity for a meaningful life, or a Kantian approach according to which all people have a dignity in virtue of their capacity for autonomous decision-making, where meaning is a function of the exercise of this capacity. For both moral outlooks, we could be required to help people with relatively meaningless lives.

Yet another relatively uncontroversial element of the concept of meaningfulness in respect of individual persons is that it is conceptually distinct from happiness or rightness (emphasized in Wolf 2010, 2016). First, to ask whether someone’s life is meaningful is not one and the same as asking whether her life is pleasant or she is subjectively well off. A life in an experience machine or virtual reality device would surely be a happy one, but very few take it to be a prima facie candidate for meaningfulness (Nozick 1974: 42–45). Indeed, a number would say that one’s life logically could become meaningful precisely by sacrificing one’s well-being, e.g., by helping others at the expense of one’s self-interest. Second, asking whether a person’s existence over time is meaningful is not identical to considering whether she has been morally upright; there are intuitively ways to enhance meaning that have nothing to do with right action or moral virtue, such as making a scientific discovery or becoming an excellent dancer. Now, one might argue that a life would be meaningless if, or even because, it were unhappy or immoral, but that would be to posit a synthetic, substantive relationship between the concepts, far from indicating that speaking of “meaningfulness” is analytically a matter of connoting ideas regarding happiness or rightness. The question of what (if anything) makes a person’s life meaningful is conceptually distinct from the questions of what makes a life happy or moral, although it could turn out that the best answer to the former question appeals to an answer to one of the latter questions.

Supposing, then, that talk of “meaning in life” connotes something good for its own sake that can come in degrees and that is not analytically equivalent to happiness or rightness, what else does it involve? What more can we say about this final value, by definition? Most contemporary analytic philosophers would say that the relevant value is absent from spending time in an experience machine (but see Goetz 2012 for a different view) or living akin to Sisyphus, the mythic figure doomed by the Greek gods to roll a stone up a hill for eternity (famously discussed by Albert Camus and Taylor 1970). In addition, many would say that the relevant value is typified by the classic triad of “the good, the true, and the beautiful” (or would be under certain conditions). These terms are not to be taken literally, but instead are rough catchwords for beneficent relationships (love, collegiality, morality), intellectual reflection (wisdom, education, discoveries), and creativity (particularly the arts, but also potentially things like humor or gardening).

Pressing further, is there something that the values of the good, the true, the beautiful, and any other logically possible sources of meaning involve? There is as yet no consensus in the field. One salient view is that the concept of meaning in life is a cluster or amalgam of overlapping ideas, such as fulfilling higher-order purposes, meriting substantial esteem or admiration, having a noteworthy impact, transcending one’s animal nature, making sense, or exhibiting a compelling life-story (Markus 2003; Thomson 2003; Metz 2013, 24–35; Seachris 2013, 3–4; Mawson 2016). However, there are philosophers who maintain that something much more monistic is true of the concept, so that (nearly) all thought about meaningfulness in a person’s life is essentially about a single property. Suggestions include being devoted to or in awe of qualitatively superior goods (Taylor 1989, 3–24), transcending one’s limits (Levy 2005), or making a contribution (Martela 2016).

Recently there has been something of an “interpretive turn” in the field, one instance of which is the strong view that meaning-talk is logically about whether and how a life is intelligible within a wider frame of reference (Goldman 2018, 116–29; Seachris 2019; Thomas 2019; cf. Repp 2018). According to this approach, inquiring into life’s meaning is nothing other than seeking out sense-making information, perhaps a narrative about life or an explanation of its source and destiny. This analysis has the advantage of promising to unify a wide array of uses of the term “meaning.” However, it has the disadvantages of being unable to capture the intuitions that meaning in life is essentially good for its own sake (Landau 2017, 12–15), that it is not logically contradictory to maintain that an ineffable condition is what confers meaning on life (as per Cooper 2003, 126–42; Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014), and that often human actions themselves (as distinct from an interpretation of them), such as rescuing a child from a burning building, are what bear meaning.