Life satisfaction index a lsia

Life satisfaction index a lsia

Рейтинг стран мира по Индексу удовлетворённости жизнью

Информация об исследовании

Общество Изучение социальных процессов.

Рейтинг качества жизни в странах мира

Индекс удовлетворённости жизнью в странах мира (Satisfaction with Life Index) — комбинированный показатель, который измеряет уровень субъективного благополучия людей в странах мира. Индекс и методология исследования разработаны в 2006 году Эдрианом Уайтом (Adrian G. White), социальным психологом из Университета Лечестера, Великобритания.

В настоящее время считается, что понятие счастья или удовлетворённости жизнью — одно из наиболее важных направлений исследований в области социологии, психологии, экономики и государственного управления. Показатели удовлетворённости жизнью стали особенностью нынешнего политического дискурса и часто рассматриваются в качестве определённой альтернативы показателям экономического роста, так как в целом имеют больше общего с жизнью реальных людей, чем абстрактные экономические теории.

Индекс удовлетворённости жизнью позиционируется как глобальная проекция субъективного благополучия людей на планете и основывается на статистическом анализе данных метаисследования различных опросов, индексов и других показателей по уровню счастья граждан соответствующих стран. В ходе исследования проанализированы данные, опубликованные специализированными учреждениями Организации Объединённых Наций, Всемирного банка, Организации Экономического сотрудничества и развития, Всемирной Торговой организации, Gallup, Economist Intelligence Unit, New Economics Foundation, других международных организаций и национальных институтов — всего более 100 различных исследований по всему миру. Полученные данные также проанализированы в отношении здоровья, экономического благосостояния и доступа к образованию. Подробное описание методологии формирования Индекса и источников данных для него приводится в работе «A Global Projection of Subjective Well-being: A Challenge To Positive Psychology?»

Результаты исследования

В этом разделе представлен актуальный (периодически обновляемый в соответствии с последними результатами исследования) список стран мира, упорядоченных по Индексу удовлетворённости жизнью их жителей. Текущее исследование охватывает 178 государств (данные опубликованы в 2006 году).

Life Satisfaction

The Life Satisfaction Index-version A (LSIA)51 is a 20-item questionnaire providing a cumulative score acknowledged as a valid index of quality of life.

Related terms:

Life Satisfaction

Focus of Life Satisfaction Research

Life satisfaction is one of the oldest research issues in the social scientific study of aging. Initially, this research focused on pathology and coping, but later the issue became perceptions of quality of life. Life satisfaction and other subjective well-being measures have been of considerable importance in gerontology. Researchers and policy makers are attempting to better understand the impact on quality of life of disability, changes in health status, caregiving, bereavement, retirement, role transitions and loss, diminishing social networks, modifications in activity involvement, and personality development over the life course.

Two issues have dominated research on subjective well-being in the field of gerontology. The first concerns how best to conceptualize and measure subjective well-being. Life satisfaction is only one of several competing subjective well-being constructs, and researchers continue to work at developing appropriate measures. The second issue involves the identification of those factors in people’s lives that influence their subjective well-being. A substantial amount of research focusing on this issue and using the life satisfaction construct has been reported. The impact on life satisfaction of various interventions, programs, and policies directed at older adults has also been of recent interest.

Measures of Life Satisfaction Across the Lifespan

Convergent/Concurrent

The LSITA scores correlate positively with the Salamon-Conte Life Satisfaction in the Elderly Scale (SCLSES; Salamon & Conte, 1984 ). For example, Barrett and Murk (2006) reported a correlation of r=.78 between the total scores of the LSITA and SCLSES. The corresponding domain scores showed correlations between r=.56 (LSITA congruence of goals – SCLSES goals) and r=.75 (LSITA zest vs. apathy – SCLSES daily activities). The correlation between the LSITA and the SWLS ( Diener et al., 1985 ) also exceeded r=.50 ( Barrett & Murk, 2006 ).

Successful Aging in Women

The Life Satisfaction Inventory

The Life Satisfaction Index-version A (LSIA) 51 is a 20-item questionnaire providing a cumulative score acknowledged as a valid index of quality of life. Dimensions of the scale include zest for life; resolution and fortitude; congruence between desired and achieved goals; high physical, psychological, and social self-concept; and a happy, optimistic mood. Participants agree or disagree with the statements and a total scale score is based on number of agreements such that higher scores indicate better life satisfaction. Specific test items include questions such as: ‘as I grow older, things seem better than I thought they would be’ and ‘as I look back on my life, I am fairly well satisfied’. It is a widely used instrument and has prior evidence of an inter-rater reliability of 0.78 and validity based on relationships with other measures of life satisfaction. 51

Well-being (Subjective), Psychology of

5 Cultural Differences in SWB

Certain variables predict life satisfaction in some cultures, but not in others (Diener and Suh 2000 ). For example, self-esteem is a strong correlate of satisfaction in highly westernized, individualistic cultures, but not in collectivistic societies where the group is more important in defining who one is. Similarly, consistency and acting in congruence with the self are stronger predictors of SWB in individualistic than in collectivistic cultures. Also, individualists on average heavily use their own emotional feelings to judge their life satisfaction, whereas collectivists are more likely to weight normative prescriptions for happiness, and the views of others. For collectivists, SWB must include the belief that significant others evaluate one’s life well. The explanation for these differences between nations is that various cultures emphasize different values and goals, and therefore tend to make certain information chronically salient so that it is used when people judge their lives.

Not only are there cultural differences in the correlates of SWB, but average SWB levels differ across nations as well. For instance, high levels of SWB are currently reported in northern European nations, whereas much lower levels are reported in eastern European countries. Several factors seem to account for the differences between nations in SWB: wealth versus poverty, political stability versus instability and social disruption, and culture. In terms of culture, some societies seem to emphasize a positive approach to life, and the desirability of happiness. In these ‘positivity cultures’ there are higher levels of satisfaction than are predicted based on wealth or objective factors alone.

Set Point Theory and Public Policy

Data and Methods

As mentioned, the SWB data are for April–May 2007, a date prior to the onset of the Great Recession. Public policies for the unemployed may be temporarily expanded in the face of rising unemployment, and such actions may distort basic policy differences among countries due to differences in the severity of a recession and the policy responses thereto. For virtually all of the countries included here, however, unemployment rates were declining prior to the date when SWB was observed; hence, the policy measures should be indicative of fundamental differences in policy. NRR and ALMP measure policies as of the year 2006; the strictness measure is for 2011, the only year for which an estimate has been made.

Three macroeconomic variables that are typically found to be significantly related to SWB are also included in the analysis. The first is GDP per capita in the year 2006, measured in 2005 dollars of purchasing power ( Heston, Summers, & Aton, 2012 ). The second is the inflation rate, the percentage change in the level of prices from 2005 to 2006. The third is the unemployment rate for April–May 2007, the month in which life satisfaction was surveyed.

Note that the unemployment rate may itself be viewed as a labor market policy variable. Differences among countries in the unemployment rate may reflect, in part, differences in fiscal and monetary policies aimed at achieving full employment. But unemployment differences may also be due to nonpolicy factors underlying aggregate demand and supply.

The net replacement rate and benefit strictness indicator are measures based on legislation in each country establishing the policies relating to each. The active labor market policies variable, however, is based on spending on such policies, and may not be an accurate indicator of actual policy differences among countries. Two countries may have the same policies, but if one has a higher unemployment rate, this will induce more ALMP expenditure and lead to the impression of a policy difference on ALMP. Hence, in assessing ALMP differences across countries, it is desirable to control for unemployment, as is done in the multivariate regressions described in the following sections.

One would expect that life satisfaction would vary directly with the net replacement rate and active labor market policies, and inversely with the strictness indicator. Higher NRR and ALMP contribute to maintaining one’s income, whereas strict eligibility requirements operate in the opposite direction. With respect to the macroeconomic variables, the expectation is that life satisfaction would vary directly with GDP per capita, and inversely with both the unemployment and inflation rates. In what follows, the bivariate OLS regression relationship between life satisfaction and each of the six variables is first examined and then the multivariate relationships.

Improving Participation and Quality of Life through Occupation

Lifestyle Modifications

Work and Hidradenitis Suppurativa

A key part of life satisfaction is derived from pursuing a worthwhile occupation. This can be a challenge for individuals with HS, as they have pain and associated loss of mobility, malodorous drainage, embarrassment, and low self-esteem. Patients often report that, due to flares and pain, they are unable to go to work and may even lose their jobs due to numerous sick days. Just over 58% of patients with HS miss work, and patients missed an average of 33.6 days from work. 59 However, another study showed that patients with HS missed less work days than controls. 60 The unemployment rate of adult HS patients eligible for a job was 25.1%, compared with 6.2% for the general population in Denmark. 61 Unemployed patients more commonly suffer from extensive axillary and mammary involvement and score higher on the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). 62 No data are available on the reason for unemployment; this may be due to pain and psychological impacts or the burden of disease, which may prevent patients from undertaking education, thus diminishing employment options.

Individuals with HS should consider career options carefully, with an understanding of common triggers and the potential need for accommodations in the workplace. Hot, humid work environments should be avoided, as heat and sweat are common HS triggers. Additionally, pressure and occlusion as experienced in many jobs from sitting may be modified with a standing desk/work setting. Appropriate consultation with a career counseling professional is recommended.

Does Happiness Change? Evidence from Longitudinal Studies

Understanding Change through Stability Coefficients

A common approach to studying whether life satisfaction can change is to study stability of individual differences in life satisfaction. This approach can inform us about the extent to which rank-ordering between individuals is preserved over time. For example, if Samantha was happier than Jonathan when they were kids, will she still be happier in adulthood? Traditionally, questions such as this one are studied by examining test–retest correlations of life satisfaction over time. Higher retest correlations would indicate that rank-order was preserved to a greater degree than lower correlations. In turn, these high retest correlations would suggest that happiness does not change much, at least over the time period being studied.

Early studies on stability of individual differences in life satisfaction were almost exclusively based on two-wave designs. Moreover, they generally examined correlations over relatively short retest intervals—weeks, months, at best up to a few years (e.g., Pavot & Diener, 1993 ). Information from these studies can tell us about the extent to which individual differences are preserved over such time periods. However, they do not allow for broad conclusions about stability over time because two-wave retest correlations obscure influences of different factors on life satisfaction, some of which lead to stability and some of which lead to change ( Conley, 1984; Fraley & Roberts, 2005 ). This leads to difficulties in interpreting two-wave retest correlations in the context of stability.

Personality and Life Outcomes

Schimmack et al. assessed personality and life satisfaction in people from two relatively individualist countries (the USA and Germany) and in people from three relatively collectivist countries (Japan, Ghana, and Mexico). Their results showed that within all five countries, people who were higher in Extraversion and Emotional Stability tended to report more satisfaction with life. (This relation was due to the fact that these persons generally experienced positive emotions much more than negative emotions, a situation that usually makes people feel satisfied with their lives.) However, the link between personality and life satisfaction was somewhat stronger in the individualist countries than in the collectivist countries.

National Panel Studies Show Substantial Minorities Recording Long-Term Change in Life Satisfaction

The Dependent/Outcome Variable: Life Satisfaction

In the German and Australian panels, life satisfaction is measured on a 0–10 scale (German mean=7.0, standard deviation=1.8; Australian mean=7.8, SD=1.5). A response of 0 means “totally dissatisfied,” and 10 means “totally satisfied.” In Britain, a 1–7 scale is used (mean=5.2, SD=1.2).

Single-item measures of life satisfaction are plainly not as reliable or valid as multi-item measures, but are widely used in international surveys and have been reviewed as acceptably reliable and valid ( Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Lucas & Donnellan, 2007 ).

life satisfaction index

Recently Published Documents

TOTAL DOCUMENTS

H-INDEX

Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Properties of the Life Satisfaction Index for the Third Age—Short Form (LSITA-SF12) for Use among Ethiopian Elders

Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Properties of the Life Satisfaction Index for the Third Age—Short Form (LSITA-SF12) for Use among Ethiopian Elders

(1) Background: Self-reported measures play a crucial role in research, clinical practice, and health assessment. Instruments used to assess life satisfaction need validation to ensure that they measure what they are intended to detect true variations over time. An adapted instrument measuring life satisfaction for use among Ethiopian elders was lacking; therefore, this study aimed to culturally adapt and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Life Satisfaction Index for the Third Age—Short Form (LSITA-SF12) in Ethiopia. (2) Methods: Elderly people (n = 130) in Metropolitan cities of northwestern Ethiopia answered the LSITA-SF12 in the Amharic language. Selected reliability and validity tests were examined. (3) Result: The scale had an acceptable limit of content validity index, internal consistency, test-retest, inter-rater reliabilities, and concurrent and discriminant validities. (4) Conclusion: The Amharic language version of LSITA-SF12 appeared to be valid and reliable measures and can be recommended for use in research and clinical purposes among Amharic-speaking Ethiopian elders.

The structure of studentsʼ subjective well-being

Introduction. Subjective well-being is one of the indicators of success and a basis of person`s socio-psychological adjustment to uncertain situations and unstable social relations. The complexity of this phenomenon requires clarifying its structure. Aim. To determine the structure of studentsʼ subjective well-being. Methods. Cognitive Features of Subjective Well-Being (KOSB-4) (O. Kaliuk, O. Savchenko), Subjective Well-Being Scale (A. Perrudet-Badoux, G. Mendelsohn, J. Chiche, adapted by M. Sokolova), Life Satisfaction Index A, LSIA (B.L. Neugarten, adapted by N. Panina), Arousability and Optimism Scale, AOS (I.S. Schuller, A.L. Comunian, adapted by N. Vodopyanova). The methodological basis is a structural-functional approach. Factor and correlation analyses were done using «STATISTICA 10.0». Results. Empirical verification of the author’s model of subjective well-being revealed the existence of three independent components in its structure (cognitive-behavioral, emotional, and contrasting). Conclusions. Students’ cognitive and behavioral aspects of well-being are not separated, they form a single factor. There is a polarity in well-being in the form of positive and negative factors.

Psychometric Properties of the Health Literacy Scale Used in the Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Middle-Aged and Older People

Psychometric Properties of the Health Literacy Scale Used in the Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Middle-Aged and Older People

Health literacy, an important factor in public and personal health, is regarded as the core of patient-centered care. Older people with high health literacy are more likely to maintain a healthier lifestyle, with good control and management of chronic diseases, than those lacking or with poor health literacy. Purpose: The present study investigated the validity and reliability of the Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Aging (TLSA) Health Literacy Scale. We also evaluated the health literacy of middle-aged and older Taiwanese adults, and its probable association with health outcomes and life satisfaction. Method: We analyzed the internal consistency reliability of the nine items of the 2015 TLSA Health Literacy Scale, and their relationship with the demographic variables. Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) and the Life Satisfaction Index were used for criterion validity. Moreover, exploratory factor analysis was used to examine the construct validity and to test the known-group validity. Results: The TLSA health literacy scale has good internal consistency reliability. Criterion-related validity was supported by the fact that the health literacy score was significantly correlated with the IADL and Life Satisfaction Index. Factor analysis indicated a three-factor structure. Known-group validity was supported by the results, showing that middle-aged and older people with good self-reported health status had better health literacy. Conclusions: The TLSA health literacy scale is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring health literacy in middle-aged and older people.

Standardization of Elderly Life Satisfaction Index (LSIA)

Standardization of Elderly Life Satisfaction Index (LSIA)

Item-Level Psychometric Properties of the Life Satisfaction Index–Z

Abstract Date Presented Accepted for AOTA INSPIRE 2021 but unable to be presented due to online event limitations. The purpose of this study was to analyze the Life Satisfaction Index–Z (LSI–Z) and provide its item-level psychometric properties. Although the LSI–Z consists of two separate unidimensional and valid subscales, it demonstrated poor precision. Therefore, OT should be aware of this critical measurement issue when using this instrument in their clinical settings and must be interpreted the test scores with some caution. Primary Author and Speaker: Heesu Choi Additional Authors and Speakers: Nam Sanghun, Ickpyo Hong

The Life Satisfaction Index-A (LSI-A): Normative Data for a General Swedish Population Aged 60 to 93 Years

The Life Satisfaction Index-A (LSI-A): Normative Data for a General Swedish Population Aged 60 to 93 Years

Perbedaan Tingkat Kepuasan Hidup Ibu Bekerja dan Ibu Rumah Tangga

Perbedaan Tingkat Kepuasan Hidup Ibu Bekerja dan Ibu Rumah Tangga

Kepuasan hidup dapat dirasakan oleh semua orang, termasuk kaum ibu. Peran seorang ibu dapat dibedakan menjadi ibu bekerja dan ibu rumah tangga. Perbedaan peran tersebut dapat mempengaruhi tingkat kepuasan hidup. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengetahui perbedaan tingkat kepuasan hidup ibu bekerja dan ibu rumah tangga pada Ibu PKK Desa Kaligung Kecamatan Blimbingsari Kabupaten Banyuwangi. Jenis penelitian ini adalah penelitian deskriptif. Sampel yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini yaitu 35 orang. Penelitian ini dilakukan pada Ibu PKK di Desa Kaligung, Banyuwangi. Instrumen yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini yaitu kuesioner Life Satisfaction Index. Berdasarkan hasil penyebaran kuesioner didapatkan hasil bahwa nilai rata-rata ibu bekerja sebesar 1.64 sedangkan nilai rata-rata ibu rumah tangga sebesar 1.67. Artinya, tingkat kepuasan hidup pada kelompok ibu rumah tangga lebih tinggi dibandingkan tingkat kepuasan hidup pada kelompok ibu bekerja. Hasil penelitian ini dapat digunakan sebagai dasar pengambilan keputusan perencanaan program terkait upaya peningkatan dukungan keluarga bagi seorang ibu agar lebih dapat meningkatkan kepuasan hidupnya.

The Satisfaction of Small Russian Cities’ Residents with the Quality of Their Lives: A Case Study of Perm Krai

The Satisfaction of Small Russian Cities’ Residents with the Quality of Their Lives: A Case Study of Perm Krai

The problem of population satisfaction with the quality of life is considered. The subjective perception by a person of the quality of his life is an important internal factor that affects his social well-being, satisfaction with his position, prospects, and individual spheres of society. Improving the quality of life of the population is one of the primary tasks of the authorities. Therefore, the analysis of the population’s assessment of the quality of certain aspects of their lives is important for federal and local authorities to determine priority areas of social policy, develop strategies and work plans of state institutions of various departments, etc. The article presents the results of a comparative study of differences in the subjective perception of various indicators of quality of life and satisfaction with various areas of life of people of different age groups. N.V. Panina’s “Life Satisfaction Index”, I. Karler’s technique to study the degree of satisfaction with one’s functioning in various fields, the Russified version of “MOS SF-36” for assessing the quality of life were used as research tools. The study was conducted in the cities of the Upper Kama region (the north of Perm Krai). The sample size was 600 people. Respondents are representatives of three age groups. Men and women are in equal proportions. Group distribution was carried out on the basis of the age classification proposed by the Institute of Age Physiology of the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences of the USSR: adolescence (17- to 21-year-olds); maturity (middle age (36- to 55-year-olds); elderly age (56-to 75-year-olds). Groups were equalized in quantitative composition. It has been revealed that among the residents of small regional cities, regardless of age, the general level of satisfaction with the quality of life is at an average level, among older people there is a tendency to a lower level. Life satisfaction and quality of life indicators decline with age. There are no statistically significant differences in the general life satisfaction index for people of different age groups. However, some indicators of quality of life revealed significant differences. In each age group, there is a certain resource sphere of life, the successful functioning of which is the basis of satisfaction, stability, and success. It is a marital relationship for the elderly, a professional sphere for middle-aged people, a social sphere for young people. The data obtained can help to define the priorities of social policy in regions, can be used in the development of socially-oriented technologies and programs aimed at improving of the living conditions of people.

Manifestations of the viability (resilience) of parents raising children with disabilities

Manifestations of the viability (resilience) of parents raising children with disabilities

The paper presents the results of an empirical study of the viability, hardiness and life satisfaction index of parents raising children with disabilities in Khabarovsk city, Russian Federation. According to the results of the study, parents who raise children with disabilities show deteriorated performance on all tests. As a result of the analysis on the viability tests and the “life satisfaction index”, statistically significant differences were revealed between the two groups of the sample; on the hardiness test, such differences were shown only on one of the scales. It was found that viability for parents of children with disabilities is not a full resource. The study confirmed the key role of the indicator “meaningfulness of life” as a “vertical” factor of viability. According to the data obtained using the “Life satisfaction index” test, the most powerful influence on the value of the life satisfaction index of parents raising children with disabilities is provided by indicators of consistency between goals set and achieved and the general mood background. In addition, these indicators also strongly correlate with each other. The results of the study showed that both groups of parents who participated in the study demonstrated sufficient ability to withstand a stressful situation. Parents raising children with disabilities have a low value of the indicator “control” as an emotional and volitional element of the scale.

Multifactorial Model Of Attitudes Towards Appearance: Empirical Investigations

Multifactorial Model Of Attitudes Towards Appearance: Empirical Investigations

This study is focusing on interrelations between attitudes towards Appearance (AP), value functional significance of AP, and life satisfaction. The study is aimed at gaining a theoretical foundation of the developed Multifactorial Model of Attitudes towards AP as well as at empirical testing of the interrelations between the single factors of the model and their combined influence on life satisfaction. It is hypothesised that a different combination of the single factors of the Multifactorial Model of Attitudes towards AP has a different impact on life satisfaction. The participants were 86 females and 86 males aged between 17 and 25 years. The inventory “Diagnostics of Real Structure of Personality Value Orientations” (Bubnova, 1999) the questionnaires “Significance of AP in Various Life Situations” (Labunskaya & Serikov, 2018), Attitudes towards AP, Satisfaction and Concern” (Labunskaya & Kapitanova, 2016), the AP Perfectionism Scale (APPS) (Srivastava, 2009) and the Life Satisfaction Index developed by Neugarten and adopted by N. V. Panina (1993) were administered. The factorial analysis revealed two types of interrelations that relate to different components of the developed Multifactorial Model of Attitudes towards AP. The results showed that considering AP as a value, attributing of higher significance to AP in various interaction contexts as well as higher AP perfectionism lead to lower life satisfaction.

Services

Support

Links

The ScienceGate team tries to make research easier by managing and providing several unique services gathered in a web platform

Comparative Study of the Effects of Tai Chi and Square Dance on Immune Function, Physical Health, and Life Satisfaction in Urban Empty-Nest Older Adults

Objective: To compare the effects of Tai Chi and Square dance on immune function, physical health, and life satisfaction in urban, empty-nest older adults.

Methods: This cross-sectional study included 249 older adults (60–69 years) who were categorized into Tai Chi (n = 81), Square dance (n = 90), and control groups (n = 78). We evaluated immunoglobulin G (IgG) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity by MTT assay, physical health indices by physical fitness levels, and life satisfaction by Life Satisfaction Index A (LSIA) scores.

Results: Immune function, physical health, and life satisfaction in older adults in the Tai Chi and Square dance groups were significantly better than those in the control group (P 0.05). Further, there was a significant correlation between LSIA scores and immune function (r = 0.50, P = 0.00) and physical health (r = 0.64, P = 0.00).

Conclusion: (1) Both Tai Chi and square dance practitioners had better health outcomes, compared with sedentary individuals; (2) Tai Chi practitioners had better physical health and immune function than Square dance practitioners. (3) Tai Chi and Square dance exercises had similar effects on life satisfaction among urban empty-nest older adults.

Suggestions: For urban empty-nest older adults who want to have better physical health and immune function, long-term Tai Chi exercise may be a better choice; however, those who are concerned about life satisfaction can choose either Tai Chi or Square dance exercise.

Introduction

Due to market reform, economic restructuring, the miniaturization of the family structure, and population aging in China, approximately 50% of the older adults in China are currently empty nesters (Zhen, 2016); it is estimated that by 2030, the proportion will reach 90% (Wang G. et al., 2017). Compared with regular older adults, empty nesters constitute a special group of older adults who are prone to suffering from “empty nest syndrome,” which is characterized by a series of psychological disorders, such as feelings of loneliness, emptiness, and depression, which adversely affect their mental health (Guo and Sun, 2018). Mental health not only contributes considerably to life satisfaction but also to immune function. For example, physical and mental health potentially influence life satisfaction in older adults (Pinto et al., 2016; Lombardo et al., 2018), and psychoneuroimmunology studies have indicated that thoughts, emotional patterns, and psychological dynamics are strongly interrelated with immune response (Vasile, 2020). Another research has demonstrated a positive correlation of increased job satisfaction with natural killer (NK) cell number and plasma immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentration (Nakata et al., 2013) as well as a significant relationship between mental resilience, perceived immune function, and health (Van Schrojenstein Lantman et al., 2017).

Hence, life satisfaction is an important psychological factor reflecting the mental health and quality of life of older empty nesters (Zou and Yang, 2017), and it is an abstract and synthetic concept, which involves spiritual, physical, and social factors of individuals in daily life (Holmes and Dickerson, 1987). Since feelings of loneliness, depression, and emptiness, among others, are common in older empty nesters and are associated with adverse health consequences from both mental and immune health perspectives, an intensified focus on introducing more effective intervention strategies targeted at mitigating these feelings, is imperative. It is also important to improve their mental health, immune function, and life satisfaction.

Currently, non-pharmacological strategies, such as exercise, are becoming more popular because of their multifunctional effects and the uncertain efficacy and possible side effects of pharmacological strategies. To date, several kinds of fitness programs, such as Tai Chi and Square dance exercises, have been adopted by the older population in China. Tai Chi exercise is a traditional Chinese physical exercise characterized by meditation and low-to-moderate intensity activity, and it is practiced worldwide by older adults. In addition to improving muscle strength (Manson et al., 2013b; Wehner et al., 2021), balance (Wehner et al., 2021), body mass index (Manson et al., 2013a,b), and systolic blood pressure (SBP) (Manson et al., 2013a), research has also found Tai Chi exercise to have favorable effects on immunity (Yeh et al., 2006; Ho et al., 2013)as well as physical and mental health in older adults (Holly and Helen, 2012; Zheng et al., 2017). Square dance is considered an expansion of line dancing and was introduced in 2004, to China (Li, 2011). Public places where dance sessions are usually conducted consist of music, companions, and leader(s); further, because it is easy to learn and it produces a cheerful atmosphere, Square dance is significantly popular among middle-aged and older Chinese adults, especially among older women. Research has revealed the positive effects of Square dance on depressive symptoms and quality of life-related mental well-being (Wang et al., 2020), physical health and psychological mood (Sun and Wang, 2020), and immunity (Pei et al., 2013) in older adults. To the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have investigated the effectiveness of Square dance, and no study has comparatively evaluated the effects of Tai Chi and Square dance on mental health and immune function in the older population. Research on the differences in effect on mental health and immune function between Tai Chi and Square dance may offer positive guidance to older adults in selecting an appropriate exercise program.

The purpose of this study was to compare the effects of Tai Chi and Square dance exercises on immunity and life satisfaction in empty-nest older adults. We also aimed to evaluate the effects of these exercise on other physical health indicators, including waist-to-hip ratio, SBP, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), vital capacity, resting pulse, and balance. We hypothesized that (1) both Tai Chi and Square dance exercises can have better effect on immunity, physical health, and life satisfaction in empty-nest older adults, (2) Tai Chi exercise has more better effect than Square dance on all the aforementioned indicators in empty-nest older adults, and (3) a significant correlation exists between these indicators.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

In this cross-sectional study, 249 empty-nest older adults aged 60–69 years were recruited and categorized into Tai Chi (n = 81, female/male [F/M] = 61/20), Square dance (n = 90, F/M = 65/25), and control group (n = 78, F/M = 60/18). In the Tai Chi and Square dance groups, empty-nest older adults were recruited by cluster sampling and those in the control group with the help of communities. The inclusion criteria for empty-nest older adults in the Tai Chi and Square dance groups were as follows: (1) empty-nest older adults: those without offspring or whose offspring lived in other places; (2) aged 60–69 years; (3) unlimited by gender; (4) engagement in regular exercise for at least 2 years, no less than 120 min/week, and more than 3 times/week; (5) no obvious diseases, such as neurological, cardiovascular, psychiatric, and/or metabolic disease prior to the exercise. The control participants are sedentary due to our choice, because the subjects in Tai Chi or Square dance group only do regular Tai Chi or Square dance exercise, so subjects are sedentary in control group is one of our inclusion criteria.

A sedentary lifestyle was defined as not having participated in exercise for more than once per week for the last year (Audette et al., 2006). All the eligible literate participants provided written informed consent, and for the illiterate ones, the consent statement was read out and signed by the researcher after obtaining their permission. The study’s protocol was approved by Ethics Committee of Wenzhou University (WZU-083).

Exercise

Tai Chi and Square dance sessions are in the form of a self-organized clubs. Each club has a chief organizer who is responsible for its leadership. Music is being played during exercise. Tai Chi exercises are conducted in the morning (6:00–7:10 a.m.) and Square dance in the evening (7:00–8:10 p.m.), with the exercise venue being a park or square.

Measures

Physical Health

Waist-to-Hip Ratio

Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) is the ratio of the circumference of the waist to that of the hips. We employed measurement methods used by previous researchers (Yang et al., 2017). Waist circumference was measured at a level midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest using a measuring tape, and hip circumference was measured using the same tape at the widest position of the buttocks, with the tape along a plane parallel to the floor and not compressing the skin, after inhalation and exhalation. Waist and hip circumferences were measured three times for each participant and were accurate to the nearest 0.1 cm, with the average of the three measurements being used for further data analysis.

Blood Pressure and Resting Heart Rate

According to the American Heart Association’s standardized protocol (Perloff et al., 1993), we measured SBP, DBP, and resting heart rate (RHR) three times for each participant using an electronic sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM-7071A, Japan), after having them sit for at least 5 min. In cases where there was a difference of more than 5 mmHg or 5 beats/min, the two closest values were adopted (Wang P. et al., 2017). We encouraged participants to avoid alcohol, cigarette smoking, coffee, tea, and excessive exercise for at least 30 min prior to measuring their blood pressure and pulse rate (Wang et al., 2012).

Vital Capacity

Vital capacity (VC) is the maximum volume of air exhaled slowly and completely after trying to inhale, that is, VC (mL) = tidal volume + expiratory reserve volume + inspiratory reserve volume (Liu et al., 2017).

We measured VC using previously described methods (Huang et al., 2019). Briefly, VC was measured using a spirometer (Jianmin, GMCS-III type A, Xinheng Oriental Technology Development Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) according to the National Physical Health Test standard guidelines of China as per the following protocol: (1) in a standing position, take 1–2 deep breaths; (2) hold the Venturi handle (the pressure hose is above the Venturi); (3) shift the head slightly backward; (4) attempt to inhale deeply until one can no longer breathe in; and (5) subsequently exhale steadily into the mouthpiece for as long as possible until there is no air left. The maximum value was recorded after three acceptable maneuver attempts. The average of the three measurements was used for further data analysis.

One-Leg Standing With Eyes Closed

We used the method described in the National Physical Health Test standard guidelines of China. Briefly, upon the assessor’s command, participants were asked to lift the non-dominant leg off the ground and keep their dominant leg vertical; in this position, participants were asked to stand for as long as possible with the time measured to the nearest to 0.01 s using a stopwatch (JinQue, JD-3B, Shanghai Automation Instrument Co., Ltd.). Before the test measurement was conducted, participants practiced 3–5 trials in the same position as that used in the official measurement. The test was stopped when participants were no longer able to maintain the requirements of the test position.

Immune Function

Overnight fasting peripheral venous blood (2 mL) was collected by qualified nurses from all participants at approximately the same time (7:30 a.m.) in a vacuum tube (Cangzhou Yongkang Pharmaceutical Products Co., Ltd., China) for measurement of IgG, Interleukin-2 (IL-2) and NK cell cytotoxicity levels, and forbid exersing, drinking and coffee the night before last.

Immunoglobulin G and Interleukin-2

We measured IgG and IL-2 levels using previously reported methods (Meng et al., 2019). The blood samples were centrifuged at 10,000 r/min for 10 min; thereafter, we collected the serum to measure the concentrations of IgG and IL-2 using the commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was measured using an ELISA reader (Bio-Rad, California, United States).

Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity

We used peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to assess NK cell cytotoxicity. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Hypaque (Tianjin Haoyang Biological Manufacture Co., Ltd., China) according to the manufacturer’s operation manual. We performed the proliferation and cytotoxicity assays using freshly isolated PBMCs.

Natural Killer Cell Isolation and Purification

PBMCs in the middle cloud layer were extracted using density gradient centrifugation and washed twice using phosphate buffer solution (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd.); To every 10 7 cells, 70 μL buffer was added for resuspension, followed by 20 μL CD56 magnetic bead antibody, and subsequently incubated at 2–8°C for 15 min; 1 mL buffer was added for uniform mixing, centrifuged at 300 r/min for 5 min, and subsequently resuspended in 500 μL buffer. The MS separation column was placed in a MiniMACS TM separation magnetic field (Miltenyi Biotec, German), and the column wall was wetted with 500 μL buffer before use; the collecting tube was set in place and the resuspended cells placed on the column, and the column was subsequently washed with 3 × 500 μL buffer. Finally, the separation column was separated from the magnetic field, placed on a new collection tube, and 1 mL buffer was promptly injected to flush down NK cells. NK cells were collected and cultured. A small number of NK cells were labeled with CD56-FITC to verify if the purity exceeded 95%.

Natural Killer Cell Culture

The NK cells’ density was adjusted to 2 × 10 5 /mL. Inoculation was performed in 96-well plates in the RPMI 1640 culture system containing 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum and IL-2 (100 U/mL) and cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Natural Killer Cytotoxicity Measurement

NK cells cultured for 48 h were effector cells (E), and K562 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were target cells (T), with E:T = 20:1. Simultaneously, three parallel multiple pores, namely, the target cell pore, effector cell pore, and medium blank control pore, were set up and cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 12 h. CCK-8 (10 μL; Dojindo, Japan) was added to each well and recultured for 4 h. Absorbance (OD value) was determined using a microplate reader at 450 nm wavelength as previously described (Mehla et al., 2010), and the average value was used for further analysis. Cytotoxicity = (1– [OD value of effector pore of target cell—OD value of effector pore]/OD value of target cell) × 100%.

Life Satisfaction Index A

This scale includes 20 items, and each item has three options, namely, “agree,” “disagree,” and “uncertain.” The total score was the sum of each item, with a score range of 0–20 points; a higher score indicated a higher life satisfaction (Neugarten Bernice et al., 1961).

Data Analysis

Demographic Characteristics

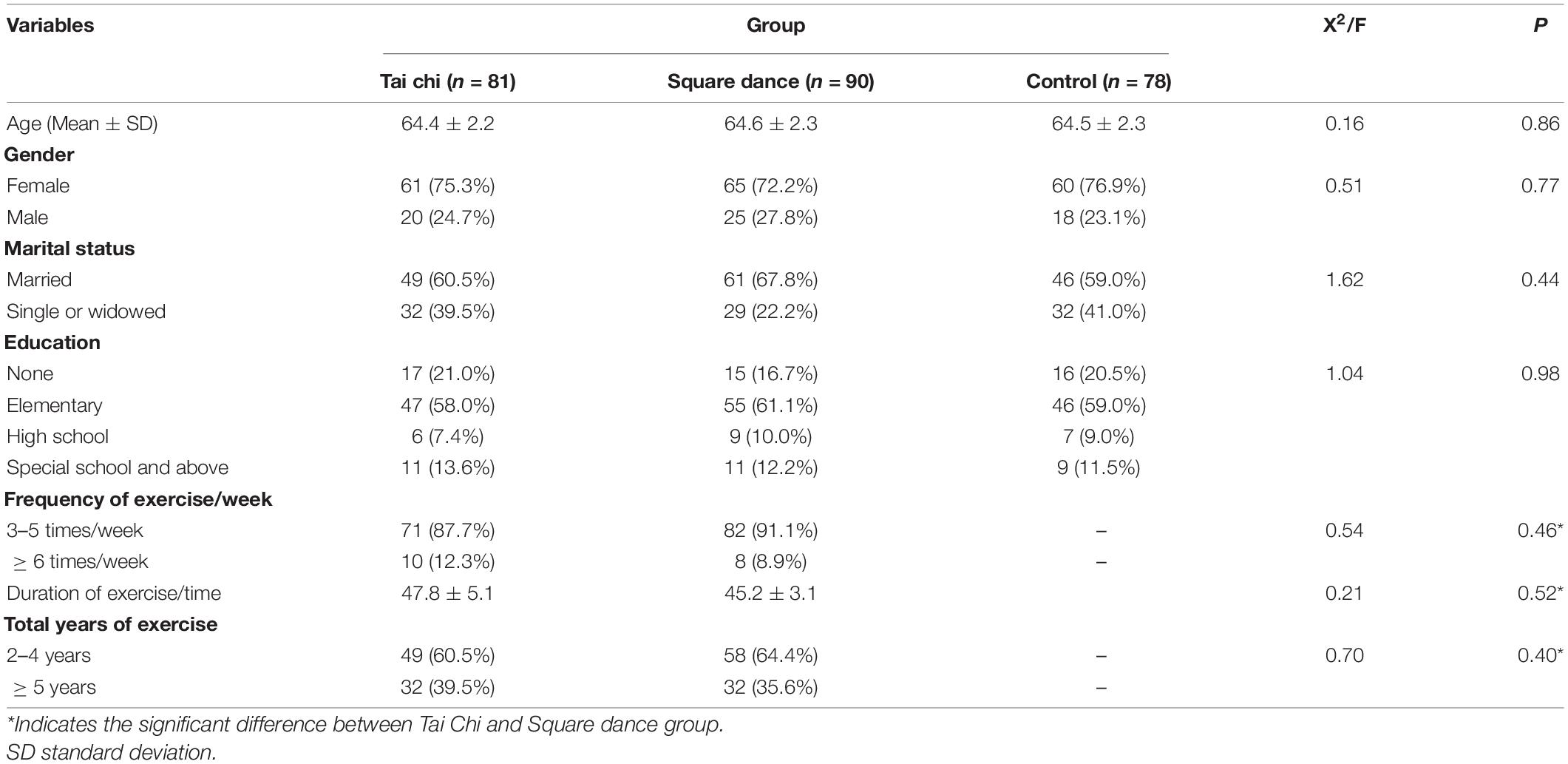

There were 81, 90, and 78 participants in the Tai Chi, Square dance, and control groups, respectively, with average ages of 64.4 ± 2.2, 64.6 ± 2.3, and 64.5 ± 2.3 years, respectively. No significant differences were observed in demographic data across the three group, almost three quarters of the participants in the three groups were women. The majority of the participants in the Tai Chi and Square dance groups reported that they had not participated in other forms of regular exercise, except for occasional walking; the same was reported in the control group. No statistically significant differences in demographic variables were observed across the three groups or between Tai Chi and Square dance group (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics of the participants in the three groups (n = 249).

Immunity of the Participants

Compared with the control group, Tai Chi and Square dance significantly improved IgG, IL-2, and NK cytotoxicity levels (p 0.05). Further, there were significantly different effects on immunity and physical health indicators as well as life satisfaction (p 0.05).

The reason underlying the different effects of the Tai Chi and Square dance exercises may be their unique characteristics. Tai Chi exercise integrates physical, psychosocial, spiritual, and behavioral components to promote mind-body interactions (Wang, 2011). It is a moderate-intensity exercise, as no more than 55% maximal oxygen intake is required (Wang et al., 2004), and it should be practiced in harmony with the Tai Chi philosophy by utilizing and manipulating Qi via Tai Chi exercise (Zheng et al., 2017). Qi is a very important concept in Chinese classical philosophy and medicine. It is not a body organ which can be anatomically identified by its location like the chakras of yoga (Cho et al., 2019). In Tai Chi exercise, it is emphasized that “Qi sinks into Dantian,” “Qi runs all over the body,” and “middle Qi passes through the top,” all of which is important to eliminate diseases and improve human function. Smooth flow of Qi makes the body comfortable, and stagnation makes the body sick. Although a deep understanding of the essence of Qi is still lacking, one can feel the existence of Qi while practicing Tai Chi exercise, as smooth flow of Qi improves fingertip numbness, distension, etc.

Square dance, which integrates Chinese style dancing and music with energetic and similar rhythms (Zhou, 2014), introduced in China around 2004 and considered an expansion of line dancing (Li, 2011), is just a medium-intensity exercise. Research shows that Tai Chi exercise has significantly better effect on cognitive function and emotion in older people than Square dance (Zhang et al., 2014), as well as better effect on enhancing lower extremity strength, balance, and flexibility than brisk walking (Audette et al., 2006). Davidson et al. (2003) directly found that an 8-week clinical training program in mindfulness meditation significantly increases the left-sided anterior activation and immune function, and that activated left-sided anterior of the brain was associated with enhanced NK-cell activity (Kang et al., 1991; Davidson et al., 1999). Irwin et al. (2003) confirmed that Tai Chi potentially increases varicella-zoster virus specific cell-mediated immunity in older adults and potentially improves T-helper cell function (Yeh et al., 2009). Tai Chi exercise, which focuses on producing inner calmness, would have both physical and psychological therapeutic value (Docker, 2006). Therefore, we have reason to believe that the comprehensive nature of Tai Chi exercise rendered it significantly superior to Square dance in improving physical health and immune function.

The mechanism underlying Tai Chi exercise’s ability to significantly increase immune function compared with Square dance may be related to a more pronounced increase in antibody titer, telomerase activity, reverse gene expression, reduced DNA damage, etc. Jacobs et al. (2011) found that meditation training could suppress immune cell aging because meditation can significantly increase immunocyte telomerase activity in normal people. Moreover, Goon et al. (2008) found that practicing Tai Chi exercise for 7 years provided a significantly effective DNA repair mechanism, reduced DNA damage, and increased lymphocyte apoptosis and proliferation in older adults; the upregulated lymphocyte apoptosis and proliferation with Tai Chi exercise may also be beneficial in preventing replicative senescence during aging. Our study also found Tai Chi exercise to be significantly effective in improving WHR (p Keywords : Tai Chi, Square dance, immune function, physical health, life satisfaction, empty nest elderly

Citation: Su Z and Zhao J (2021) Comparative Study of the Effects of Tai Chi and Square Dance on Immune Function, Physical Health, and Life Satisfaction in Urban Empty-Nest Older Adults. Front. Physiol. 12:721758. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.721758

Received: 09 July 2021; Accepted: 14 September 2021;

Published: 05 October 2021.

Mallikarjuna Korivi, Zhejiang Normal University, China

Siew Cheok Ng, University of Malaya, Malaysia

Yuewei Liu, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Copyright © 2021 Su and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: JieXiu Zhao, zhaojiexiu@ciss.cn

This article is part of the Research Topic

Nutritional and Physical Activity Strategies to Boost Immunity, Antioxidant Status and Health, Volume II

Happiness and Life Satisfaction

First published in 2013; substantive revision May 2017.

The French translation of this entry is here: Bonheur et satisfaction

How happy are people today? Were people happier in the past? How satisfied with their lives are people in different societies? And how do our living conditions affect all of this?

These are difficult questions to answer; but they are questions that undoubtedly matter for each of us personally. Indeed, today, life satisfaction and happiness are central research areas in the social sciences, including in ‘mainstream’ economics.

Social scientists often recommend that measures of subjective well-being should augment the usual measures of economic prosperity, such as GDP per capita. 1 But how can happiness be measured? Are there reliable comparisons of happiness across time and space that can give us clues regarding what makes people declare themselves ‘happy’?

In this entry, we discuss the data and empirical evidence that might answer these questions. Our focus here will be on survey-based measures of self-reported happiness and life satisfaction. Here is a preview of what the data reveals.

All our interactive charts on Happiness and Life Satisfaction

Happiness across the world today

The World Happiness Report is a well-known source of cross-country data and research on self-reported life satisfaction. The map here shows, country by country, the ‘happiness scores’ published this report.

The underlying source of the happiness scores in the World Happiness Report is the Gallup World Poll—a set of nationally representative surveys undertaken in more than 160 countries in over 140 languages. The main life evaluation question asked in the poll is: “Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?” (Also known as the “Cantril Ladder”.)

The map plots the average answer that survey-respondents provided to this question in different countries. As with the steps of the ladder, values in the map range from 0 to 10.

There are large differences across countries. According to the most recent figures, European countries top the ranking: Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Switzerland and the Netherlands have the highest scores (all with averages above 7). In the same year, the lowest national scores correspond to Afghanistan, Lebanon, Zimbabwe, Rwanda and Botswana (all with average scores below 3.5).

You can click on any country on the map to plot time-series for specific countries.

As we can see, self-reported life satisfaction correlates with other measures of well-being—richer and healthier countries tend to have higher average happiness scores. (More on this in the section below.)

Click to open interactive version

Happiness over time

Findings from the World Value Survey

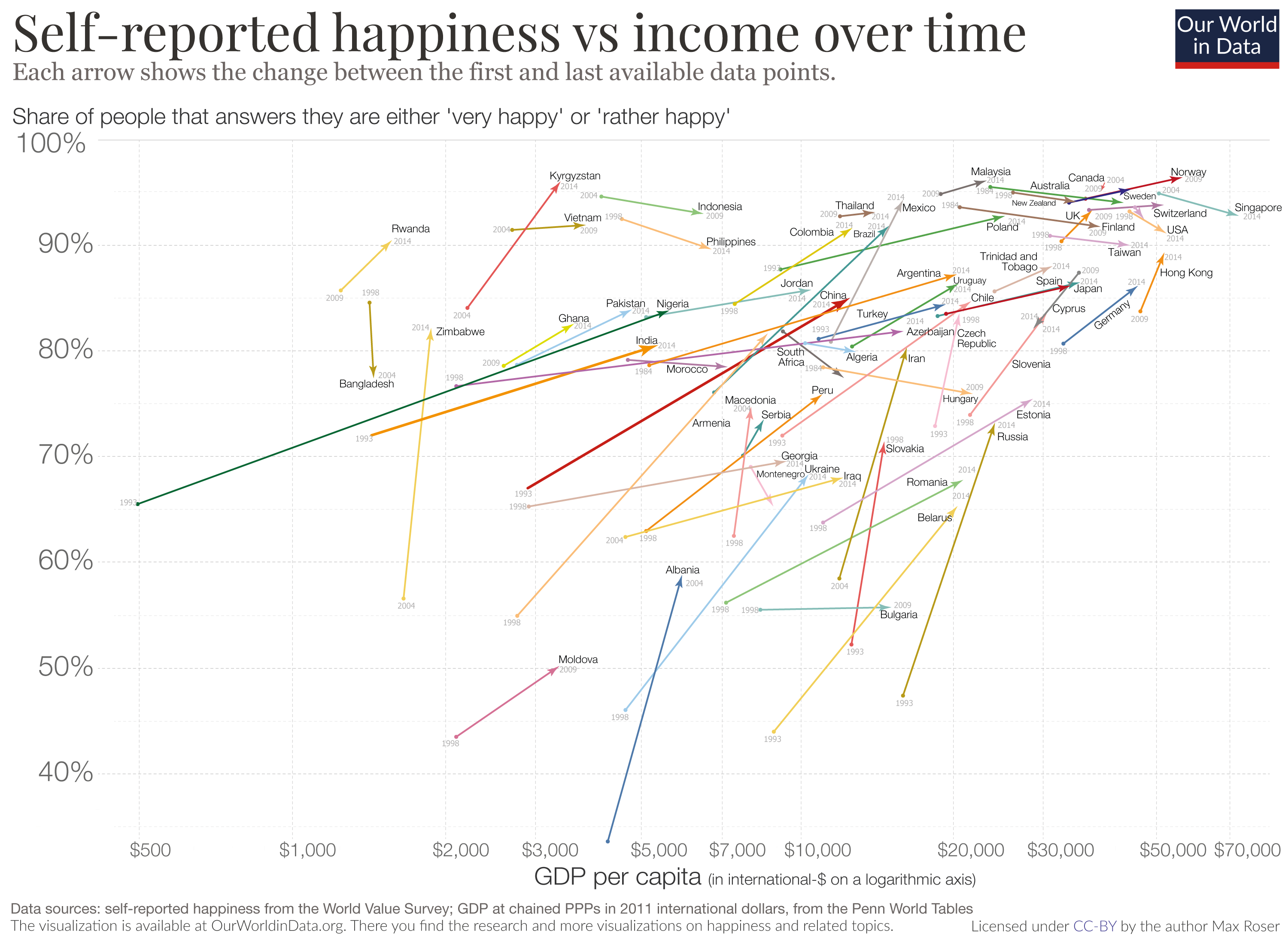

In addition to the Gallup World Poll (discussed above), the World Value Survey also provides cross-country data on self-reported life satisfaction. These are the longest available time series of cross-country happiness estimates that include non-European nations.

The World Value Survey collects data from a series of representative national surveys covering almost 100 countries, with the earliest estimates dating back to 1981. In these surveys, respondents are asked: “Taking all things together, would you say you are (i) Very happy, (ii) Rather happy, (iii) Not very happy or (iv) Not at all happy”. This visualization plots the share of people answering they are Very happy or Rather happy.

As we can see, in the majority of countries the trend is positive: In 49 of the 69 countries with data from two or more surveys, the most recent observation is higher than the earliest. In some cases, the improvement has been very large; in Zimbabwe, for example, the share of people who reported being ‘very happy’ or ‘rather happy’ went from 56.4% in 2004 to 82.1% in 2014.

Click to open interactive version

Findings from Eurobarometer

The Eurobarometer collects data on life satisfaction as part of their public opinion surveys. For several countries, these surveys have been conducted at least annually for more than 40 years. The visualization here shows the share of people who report being ‘very satisfied’ or ‘fairly satisfied’ with their standards of living, according to this source.

Two points are worth emphasizing. First, estimates of life satisfaction often fluctuate around trends. In France, for example, we can see that the overall trend in the period 1974-2016 is positive; yet there is a pattern of ups and downs. And second, despite temporary fluctuations, decade-long trends have been generally positive for most European countries.

In most cases, the share of people who say they are ‘very satisfied’ or ‘fairly satisfied’ with their life has gone up over the full survey period. 2 Yet there are some clear exceptions, of which Greece is the most notable example. Add Greece to the chart and you can see that in 2007, around 67% of the Greeks said they were satisfied with their life; but five years later, after the financial crisis struck, the corresponding figure was down to 32.4%. Despite recent improvements, Greeks today are on average much less satisfied with their lives than before the financial crisis. No other European country in this dataset has gone through a comparable negative shock.

Click to open interactive version

The distribution of life satisfaction

More than averages—the distribution of life satisfaction scores

Most of the studies comparing happiness and life satisfaction among countries focus on averages. However, distributional differences are also important.

Life satisfaction is often reported on a scale from 0 to 10, with 10 representing the highest possible level of satisfaction. This is the so-called ‘Cantril Ladder’. This visualization shows how responses are distributed across steps in this ladder. In each case, the height of bars is proportional to the fraction of answers at each score. Each differently-colored distribution refers to a world region; and for each region, we have overlaid the distribution for the entire world as a reference.

These plots show that in sub-Saharan Africa—the region with the lowest average scores–the distributions are consistently to the left of those in Europe. In economics lingo, we observe that the distribution of scores in European countries stochastically dominates the distribution in sub-Saharan Africa.

This means that the share of people who are ‘happy’ is lower in sub-Saharan Africa than in Western Europe, independently of which score in the ladder we use as a threshold to define ‘happy’. Similar comparisons can be made by contrasting other regions with high average scores (e.g. North America, Australia and New Zealand) against those with low average scores (e.g. South Asia).

Another important point to notice is that the distribution of self-reported life satisfaction in Latin America is high across the board—it is consistently to the right of other regions with roughly comparable income levels, such as Central and Eastern Europe.

This is part of a broader pattern: Latin American countries tend to have a higher subjective well-being than other countries with comparable levels of economic development. As we will see in the section on social environment, culture and history matter for self-reported life satisfaction.

If you are interested in data on country-level distributions of scores, the Pew Global Attitudes Survey provides such figures for more than 40 countries.

(Mis)perceptions about others’ happiness

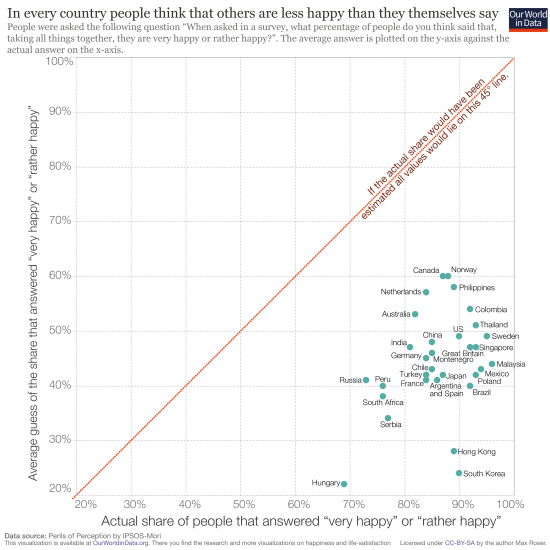

We tend to underestimate the average happiness of people around us. The visualization shown demonstrates this for countries around the world, using data from Ipsos’ Perils of Perception—a cross-country survey asking people to guess what others in their country have answered to the happiness question in the World Value Survey.

The horizontal axis in this chart shows the actual share of people who said they are ‘Very Happy’ or ‘Rather Happy’ in the World Value Survey; the vertical axis shows the average guess of the same number (i.e. the average guess that respondents made of the share of people reporting to be ‘Very Happy’ or ‘Rather Happy’ in their country).

If respondents would have guessed the correct share, all observations would fall on the red 45-degree line. But as we can see, all countries are far below the 45-degree line. In other words, people in every country underestimated the self-reported happiness of others. The most extreme deviations are in Asia—South Koreans think that 24% of people report being happy, when in reality 90% do.

The highest guesses in this sample (Canada and Norway) are 60%—this is lower than the lowest actual value of self-reported happiness in any country in the sample (corresponding to Hungary at 69%).

Why do people get their guesses so wrong? It’s not as simple as brushing aside these numbers by saying they reflect differences in ‘actual’ vs. reported happiness.

One possible explanation is that people tend to misreport their own happiness, therefore the average guesses might be a correct indicator of true life satisfaction (and an incorrect indicator of reported life satisfaction). However, for this to be true, people would have to commonly misreport their own happiness while assuming that others do not misreport theirs.

And people are not bad at judging the well-being of other people who they know: There is substantial evidence showing that ratings of one’s happiness made by friends correlate with one’s happiness, and that people are generally good at evaluating emotions from simply watching facial expressions.

An alternative explanation is that this mismatch is grounded in the well-established fact that people tend to be positive about themselves, but negative about other people they don’t know.It has been observed in other contexts that people can be optimistic about their own future, while at the same time being deeply pessimistic about the future of their nation or the world. We discuss this phenomenon in more detail in our entry on optimism and pessimism, specifically in a section dedicated to individual optimism and social pessimism.

Differences in happiness within countries

East and West Germany

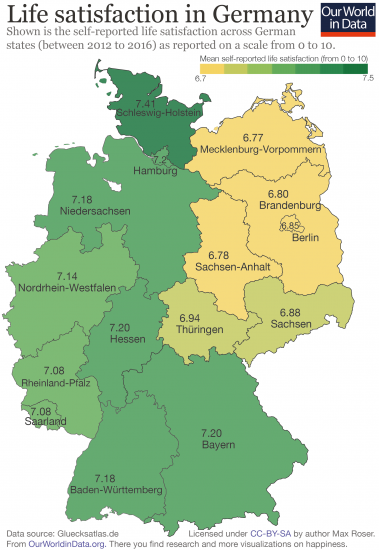

In global surveys of happiness and life satisfaction, Germany usually ranks high. However, these national averages mask large inequalities. In the map shown we focus on regional inequalities—specifically the gap in life satisfaction between West and East Germany.

This map plots self-reported life satisfaction in Germany (using the 0-10 Cantril Ladder question), aggregating averages scores at the level of Federal States. 3 What stands out is a clear divide between the East and the West, along the political division that existed before the reunification of Germany in 1990.

For example, the difference in levels between neighboring Schleswig-Holstein (in West Germany) and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in East Germany) are similar to the difference between Sweden and the US – a considerable contrast in self-reported life satisfaction.

Several academic studies have looked more closely at this ‘happiness gap’ in Germany using data from more detailed surveys, such as the German Socio-Economic Panel (e.g. Petrunyk and Pfeifer 2016). 4 These studies provide two main insights:

First, the gap is partly driven by differences in household income and employment. But this is not the only aspect; even after controlling for socioeconomic and demographic differences, the East-West gap remains significant.

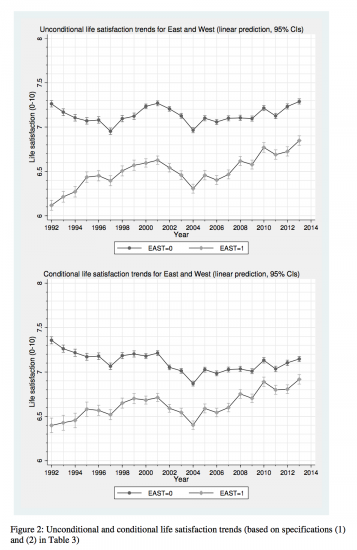

Germany’s happiness gap over time

And second, the gap has been narrowing in recent years, as the chart shows. In fact, the finding that the gap is narrowing is true both for the raw average differences, as well as for the ‘conditional differences’ (i.e. the differences that are estimated after controlling for socioeconomic and demographic characteristics).

The observation that socioeconomic and demographic differences do not fully predict the observed East-West differences in self-reported happiness is related to a broader empirical phenomenon: Culture and history matter for self-reported life satisfaction—and in particular, ex-communist countries tend to have a lower subjective well-being than other countries with comparable levels of economic development.

Trends in life satisfaction for East and West Germany, 1992-2013

Happiness inequality

Happiness inequality in the US and other rich countries

The General Social Survey (GSS) in the US is a survey administered to a nationally representative sample of about 1,500 respondents each year since 1972, and is an important source of information on long-run trends of self-reported life satisfaction in the country. 5

Using this source, Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) 6 show that while the national average has remained broadly constant, inequality in happiness has fallen substantially in the US in recent decades.

The authors further note that this is true both when we think about inequality in terms of the dispersion of answers, and also when we think about inequality in terms of gaps between demographic groups. They note that two-thirds of the black-white happiness gap has been eroded (although today white Americans remain happier on average, even after controlling for differences in education and income), and the gender happiness gap has disappeared entirely (women used to be slightly happier than men, but they are becoming less happy, and today there is no statistical difference once we control for other characteristics). 7

The results from Stevenson and Wolfers are consistent with other studies looking at changes of happiness inequality (or life satisfaction inequality) over time. In particular, researchers have noted that there is a correlation between economic growth and reductions in happiness inequality—even when income inequality is increasing at the same time. The visualization here uses data from Clark, Fleche and Senik (2015) 8 shows this. It plots the evolution of happiness inequality within a selection of rich countries that experienced uninterrupted GDP growth.

In this chart, happiness inequality is measured by the dispersion — specifically the standard deviation — of answers in the World Value Survey. As we can see, there is a broad negative trend. In their paper the authors show that the trend is positive in countries with falling GDP.

Why could it be that happiness inequality falls with rising income inequality?

Clark, Fleche, and Senik argue that part of the reason is that the growth of national income allows for the greater provision of public goods, which in turn tighten the distribution of subjective well-being. This can still be consistent with growing income inequality, since public goods such as better health affect incomes and well-being differently.

Another possibility is that economic growth in rich countries has translated into a more diverse society in terms of cultural expressions (e.g. through the emergence of alternative lifestyles), which has allowed people to converge in happiness even if they diverge in incomes, tastes and consumption. Steven Quartz and Annette Asp explain this hypothesis in a New York Times article, discussing evidence from experimental psychology.

Click to open interactive version

The link between happiness and income

The link across countries

Higher national incomes go together with higher average life satisfaction

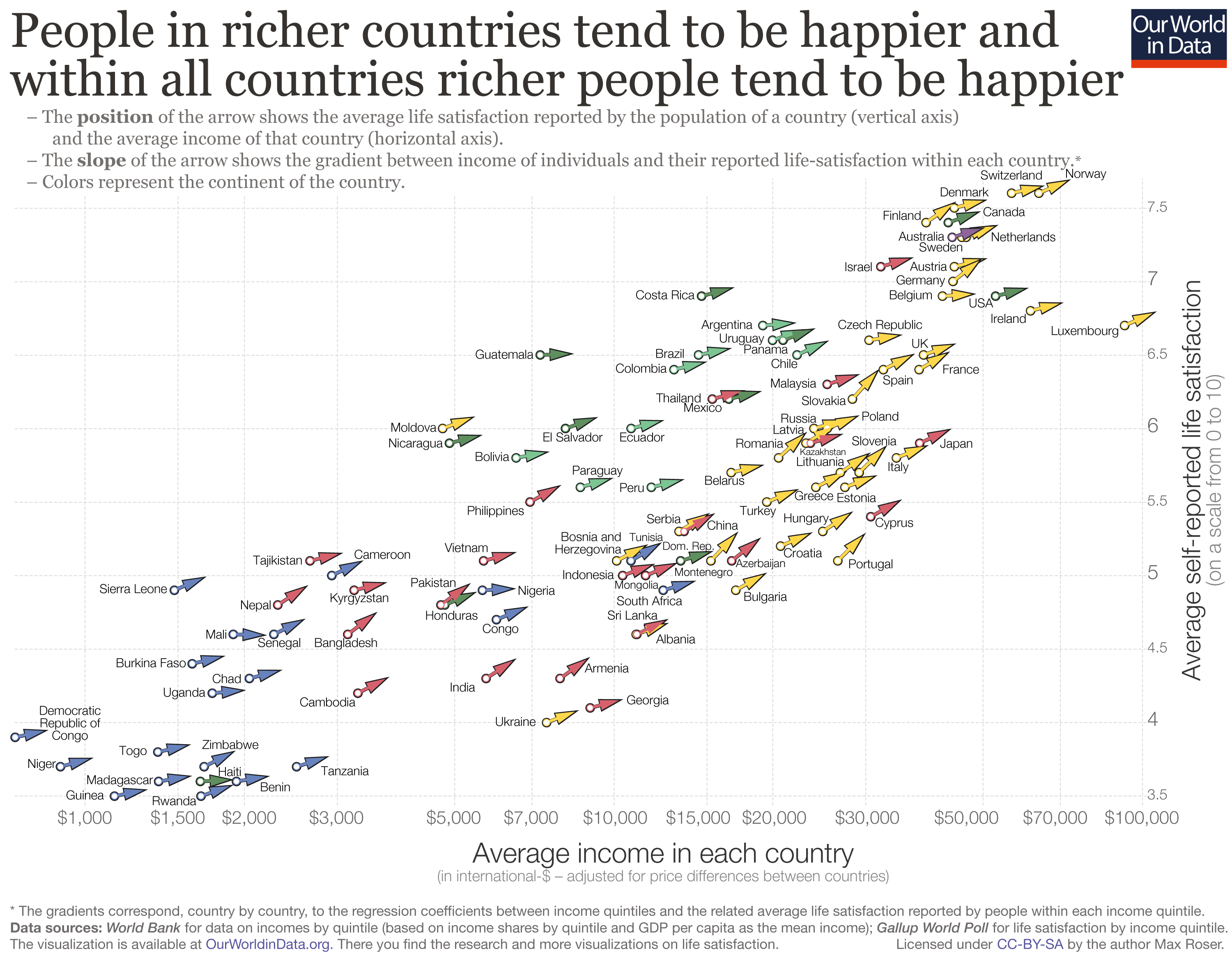

If we compare life satisfaction reports from around the world at any given point in time, we immediately see that countries with higher average national incomes tend to have higher average life satisfaction scores. In other words: People in richer countries tend to report higher life satisfaction than people in poorer countries. The scatter plot here shows this.

Each dot in the visualization represents one country. The vertical position of the dots shows national average self-reported life satisfaction in the Cantril Ladder (a scale ranging from 0-10 where 10 is the highest possible life satisfaction); while the horizontal position shows GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (i.e. GDP per head after adjusting for inflation and cross-country price differences).

This correlation holds even if we control for other factors: Richer countries tend to have higher average self-reported life satisfaction than poorer countries that are comparable in terms of demographics and other measurable characteristics. You can read more about this in the World Happiness Report 2017, specifically the discussion in Chapter 2.

As we show below, income and happiness also tend to go together within countries and across time.

Click to open interactive version

The link within countries

Higher personal incomes go together with higher self-reported life satisfaction

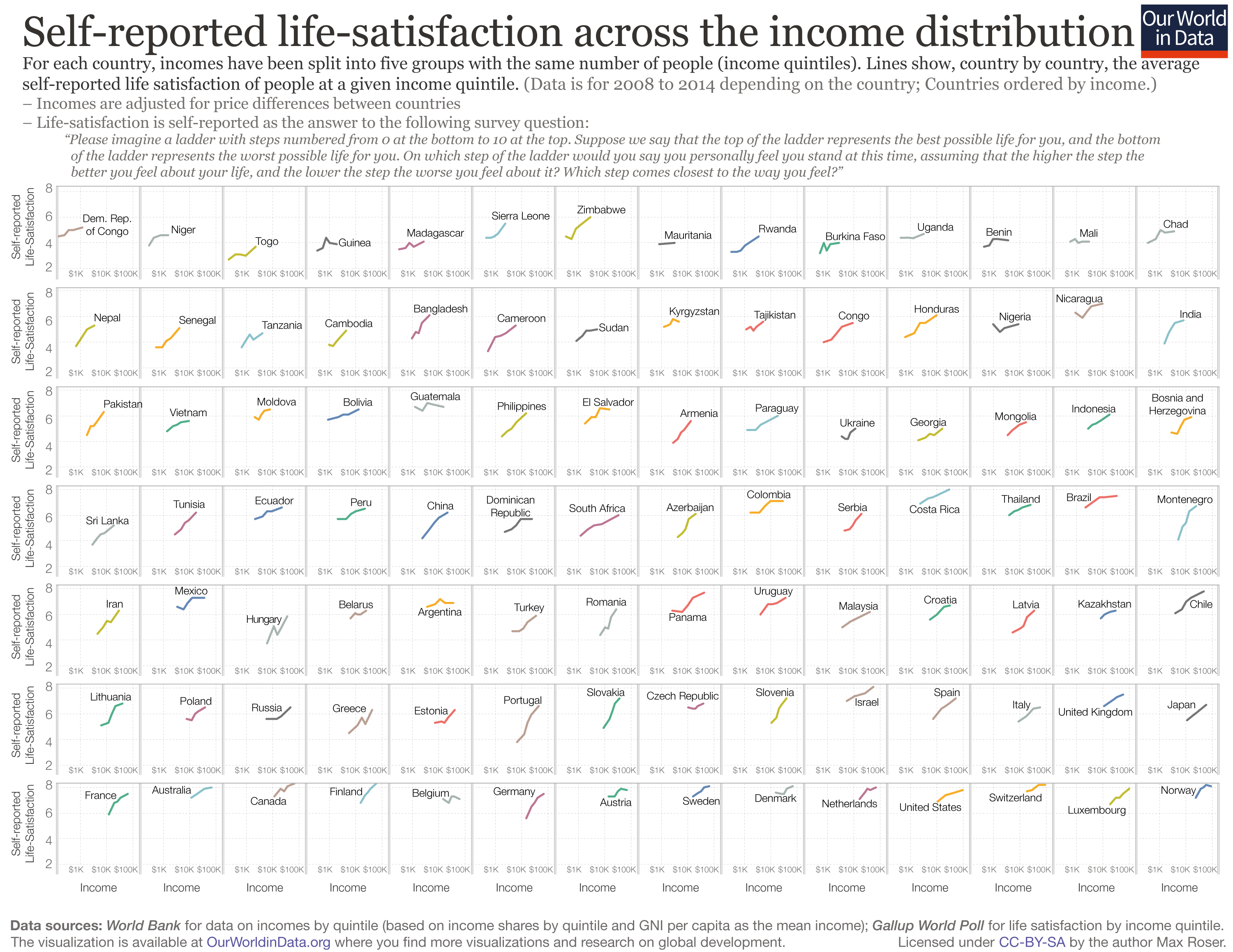

Above we point out that richer countries tend to be happier than poorer countries. Here we show that the same tends to be true within countries: richer people within a country tend to be happier than poorer people in the same country. The visualisations here show us this this by looking at happiness by income quintiles.

Firstly we show each country in individual panels: within each panel is a connected scatter plot for a specific country. This means that for each country, we observe a line joining five points: each point marks the average income within an income quintile (horizontal axis) against the average self-reported life satisfaction of people at that income quintile (vertical axis).

What does this visualization tell us? We see that in all cases lines are upward sloping: people in higher income quintiles tend to have higher average life satisfaction. Yet in some countries the lines are steep and linear (e.g. in Costa Rica richer people are happier than poorer people across the whole income distribution); while in some countries the lines are less steep and non-linear (e.g. the richest group of people in the Dominican Republic is as happy as the second-richest group).

In a second visualization we present the same data, but instead of plotting each country separately, showing all countries in one grid.

The resulting connected scatter plot may be messy, resembling a ‘spaghetti’ chart, but it is helpful to confirm the overall pattern: despite kinks here and there, lines are by and large upward sloping.

Looking across and within countries

A snapshot of the correlation between income and happiness—between and within countries

Do income and happiness tend to go together? The visualization here shows that the answer to this question is yes, both within and across countries.

It may take a minute to wrap your head around this visualization, but once you do, you can see that it handily condenses the key information from the previous three charts into one.

To show the income-happiness correlation across countries, the chart plots the relationship between self-reported life satisfaction on the vertical axis and GDP per capita on the horizontal axis. Each country is an arrow on the grid, and the location of the arrow tells us the corresponding combination of average income and average happiness.

To show the income-happiness correlation within countries, each arrow has a slope corresponding to the correlation between household incomes and self-reported life satisfaction within that country. In other words: the slope of the arrow shows how strong the relationship between income and life satisfaction is within that country. (This chart gives you a visual example of how the arrows were constructed for each country). 9

If an arrow points northeast, that means richer people tend to report higher life satisfaction than poorer people in the same country. If an arrow is flat (i.e. points east), that means rich people are on average just as happy as poorer people in the same country.

As we can see, there is a very clear pattern: richer countries tend to be happier than poorer countries (observations are lined up around an upward-sloping trend), and richer people within countries tend to be happier than poorer people in the same countries (arrows are consistently pointing northeast).

It’s important to note that the horizontal axis is measured in a logarithmic scale. The cross-country relationship we would observe in a linear scale would be different, since at high national income levels, slightly higher national incomes are associated with a smaller increase in average happiness than at low levels of national incomes. In other words, the cross-country relationship between income and happiness is not linear on income (it is ‘log-linear’). We use the logarithmic scale to highlight two key facts: (i) at no point in the global income distribution is the relationship flat; and (ii) a doubling of the average income is associated with roughly the same increase in the reported life-satisfaction, irrespective of the position in the global distribution.

These findings have been explored in more detail in a number of recent academic studies. Importantly, the much-cited paper by Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) 10 shows that these correlations hold even after controlling for various country characteristics such as demographic composition of the population, and are robust to different sources of data and types of subjective well-being measures.

Economic growth and happiness

In the charts above we show that there is robust evidence of a strong correlation between income and happiness across and within countries at fixed points in time. Here we want to show that, while less strong, there is also a correlation between income and happiness across time. Or, put differently, as countries get richer, the population tends to report higher average life satisfaction.

The chart shown here uses data from the World Value Survey to plot the evolution of national average incomes and national average happiness over time. To be specific, this chart shows the share of people who say they are ‘very happy’ or ‘rather happy’ in the World Value Survey (vertical axis), against GDP per head (horizontal axis). Each country is drawn as a line joining first and last available observations across all survey waves. 11

As we can see, countries that experience economic growth also tend to experience happiness growth across waves in the World Value Survey. And this is a correlation that holds after controlling for other factors that also change over time (in this chart from Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) you can see how changes in GDP per capita compare to changes in life satisfaction after accounting for changes in demographic composition and other variables).

An important point to note here is that economic growth and happiness growth tend to go together on average. Some countries in some periods experience economic growth without increasing happiness. The experience of the US in recent decades is a case in point. These instances may seem paradoxical given the evidence—we explore this question in the following section.

The Easterlin Paradox

The observation that economic growth does not always go together with increasing life satisfaction was first made by Richard Easterlin in the 1970s. Since then, there has been much discussion over what came to be known as the ‘Easterlin Paradox’.

At the heart of the paradox was the fact that richer countries tend to have higher self-reported happiness, yet in some countries for which repeated surveys were available over the course of the 1970s, happiness was not increasing with rising national incomes. This combination of empirical findings was paradoxical because the cross-country evidence (countries with higher incomes tended to have higher self-reported happiness) did not, in some cases, fit the evidence over time (countries seemed not to get happier as national incomes increased).

Notably, Easterlin and other researchers relied on data from the US and Japan to support this seemingly perplexing observation. If we look closely at the data underpinning the trends in these two countries, however, these cases are not in fact paradoxical.

Let us begin with the case of Japan. There, the earliest available data on self-reported life satisfaction came from the so-called ‘Life in Nation surveys’, which date back to 1958. At first glance, this source suggests that mean life satisfaction remained flat over a period of spectacular economic growth (see for example this chart from Easterlin and Angelescu 2011). 12 Digging a bit deeper, however, we find that things are more complex.

Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) 13 show that the life satisfaction questions in the ‘Life in Nation surveys’ changed over time, making it difficult—if not impossible—to track changes in happiness over the full period. The visualization here splits the life satisfaction data from the surveys into sub-periods where the questions remained constant. As we can see, the data is not supportive of a paradox: the correlation between GDP and happiness growth in Japan is positive within comparable survey periods. The reason for the alleged paradox is in fact mismeasurement of how happiness changed over time.

In the US, the explanation is different, but can once again be traced to the underlying data. Specifically, if we look more closely at economic growth in the US over the recent decades, one fact looms large: growth has not benefitted the majority of people. Income inequality in the US is exceptionally high and has been on the rise in the last four decades, with incomes for the median household growing much more slowly than incomes for the top 10%. As a result, trends in aggregate life satisfaction should not be seen as paradoxical: the income and standard of living of the typical US citizen has not grown much in the last couple of decades. (You can read more about this in our entry on inequality and incomes across the distribution.)

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Life Satisfaction Index

Abstract

Factor models of the construct of well-being in later life have shown mixed results. Here we evaluated the factor structure of the Life Satisfaction Index A (LSIA), a widely used measure. Confirmatory factor analyses using a sample of community living aged people (N = 187) suggested that a unidimensional model was not appropriate for the scale. Moreover, only two of the 10 models previously proposed for the LSIA was found to fit reasonably well. These models (Bigot, 1974; Hoyt and Creech, 1983) consisted of only eight of the 20 LSIA items. Models which utilized all 20 LSIA items tended to fit poorly, whereas, those based on subsets of items generally showed improved fit. Allowing correlated factors also improved the fit. Throughout, fit indices were computed using the Satorra-Bentler scaled test statistic because the data were not normally distributed. These results highlight the importance of theory and construct development prior to actual scale development in social indicators research.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution.

Оценка жизненной удовлетворенности человека (тест ИЖУ)

Оценка жизненной удовлетворенности человека (тест ИЖУ)

Оценка жизненной удовлетворенности человека (тест ИЖУ)

Навигация (только номера заданий)

0 из 20 заданий окончено

Информация

Опросник «Индекс жизненной удовлетворенности» (Life Satisfaction Index A, LSIA) разработан группой американских ученых в 1961 году, русскоязычная адаптация сделана Н. В. Паниной в 1993 году. Методика предназначена для оценки удовлетворенностью жизнью, интегративного показателя, под которым понимается самое общее представление человека о психологическом комфорте.

Помимо интегрального показателя, опросник позволяет выделить и оценить 5 различных аспектов удовлетворенности жизнью.

Опросник состоит из 20 вопросов.

Примерное время тестирования 5-10 минут.

Вы уже проходили тест ранее. Вы не можете запустить его снова.

Вы должны войти или зарегистрироваться для того, чтобы начать тест.

Вы должны закончить следующие тесты, чтобы начать этот:

Результаты

Вы набрали 0 из 0 баллов ( 0 )

Рубрики

Высокий индекс жизненной удовлетворенности.

Лица с высокими значениями индекса характеризуются низким уровнем эмоциональной напряженности, низким уровнем тревожности, высокой эмоциональной устойчивостью, высоким уровнем удовлетворенности ситуацией и своей ролью в ней.

Дополнительную информацию о том, какие конкретные сферы жизни приносят удовлетворение или недовольство, подскажут набранные баллы по шкалам (рубрикам). Чем выше балл по каждой шкале, тем более выражено это свойство (87.5-100% — высоко, 50-75% — средне, 0-37.5% — низко):

— интерес к жизни. Шкала отражает степень энтузиазма, увлеченного отношения к обычной повседневной жизни;

— общий фон настроения. Шкала показывает степень оптимизма, удовольствия от жизни;