Markdown code block

Markdown code block

Markdown Reference

Overview

Markdown is created by Daring Fireball; the original guideline is here. Its syntax, however, varies between different parsers or editors. Typora try to follow GitHub Flavored Markdown, but may still have small incompatibilities.

Table of Contents

Block Elements

Paragraph and line breaks

A paragraph is simply one or more consecutive lines of text. In markdown source code, paragraphs are separated by two or more blank lines. In Typora, you only need one blank line (press Return once) to create a new paragraph.

Press Shift + Return to create a single line break. Most other markdown parsers will ignore single line breaks, so in order to make other markdown parsers recognize your line break, you can leave two spaces at the end of the line, or insert

.

Headers

Headers use 1-6 hash ( # ) characters at the start of the line, corresponding to header levels 1-6. For example:

In Typora, input ‘#’s followed by title content, and press Return key will create a header. Or type ⌘1 to ⌘6 as a shortcut.

Blockquotes

Markdown uses email-style > characters for block quoting. They are presented as:

In Typora, typing ‘>’ followed by your quote contents will generate a quote block. Typora will insert a proper ‘>’ or line break for you. Nested block quotes (a block quote inside another block quote) by adding additional levels of ‘>’.

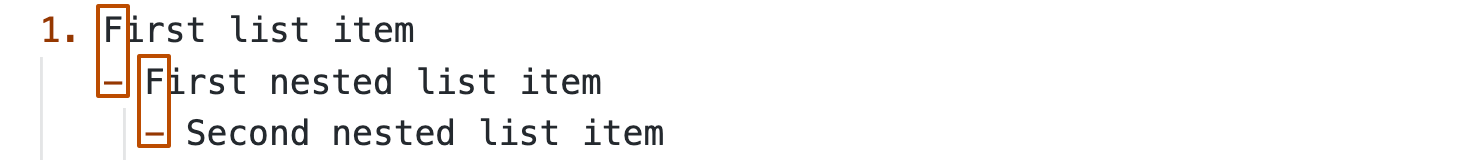

Lists

Typing 1. list item 1 will create an ordered list.

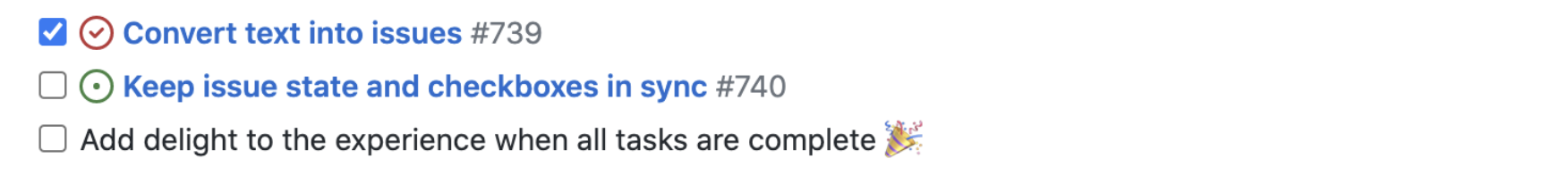

Task List

Task lists are lists with items marked as either [ ] or [x] (incomplete or complete). For example:

You can change the complete/incomplete state by clicking on the checkbox before the item.

(Fenced) Code Blocks

Typora only supports fences in GitHub Flavored Markdown, not the original code block style.

Math Blocks

You can render LaTeX mathematical expressions using MathJax.

In the markdown source file, the math block is a LaTeX expression wrapped by a pair of ‘$$’ marks:

You can find more details here.

Tables

Standard Markdown has been extended in several ways to add table support., including by GFM. Typora supports this with a graphical interface, or writing the source code directly.

Enter | First Header | Second Header | and press the return key. This will create a table with two columns.

After a table is created, placing the focus on that table will open up a toolbar for the table where you can resize, align, or delete the table. You can also use the context menu to copy and add/delete individual columns/rows.

The full syntax for tables is described below, but it is not necessary to know the full syntax in detail as the markdown source code for tables is generated automatically by Typora.

In markdown source code, they look like:

You can also include inline Markdown such as links, bold, italics, or strikethrough in the table.

By including colons ( : ) within the header row, you can set text in that column to be left-aligned, right-aligned, or center-aligned:

A colon on the left-most side indicates a left-aligned column; a colon on the right-most side indicates a right-aligned column; a colon on both sides indicates a center-aligned column.

Footnotes

MultiMarkdown extends standard Markdown to provide two ways to add footnotes.

Hover over the ‘fn1’ or ‘fn2’ superscript to see content of the footnote. You can use whatever unique identified you like as the footnote marker (e.g. “fn1”).

Hover over the footnote superscripts to see content of the footnote.

Horizontal Rules

YAML Front Matter

Table of Contents (TOC)

Enter [toc] and press the Return key to create a “Table of Contents” section. The TOC extracts all headers from the document, and its contents are updated automatically as you add to the document.

Span Elements

Span elements will be parsed and rendered right after typing. Moving the cursor in middle of those span elements will expand those elements into markdown source. Below is an explanation of the syntax for each span element.

Links

Markdown supports two styles of links: inline and reference.

In both styles, the link text is delimited by [square brackets].

Inline Links

To create an inline link, use a set of regular parentheses immediately after the link text’s closing square bracket. Inside the parentheses, put the URL where you want the link to point, along with an optional title for the link, surrounded in quotes. For example:

This is an example inline link. (

This link has no title attribute. (

Internal Links

To create an internal link that creates a ‘bookmark’ that allow you to jump to that section after clicking on it, use the name of the header element as the href. For example:

Reference Links

Reference-style links use a second set of square brackets, inside which you place a label of your choosing to identify the link:

In Typora, they will be rendered like so:

This is an example reference-style link.

The implicit link name shortcut allows you to omit the name of the link, in which case the link text itself is used as the name. Just use an empty set of square brackets — for example, to link the word “Google” to the google.com web site, you could simply write:

In Typora, clicking the link will expand it for editing, and command+click will open the hyperlink in your web browser.

Typora will also automatically link standard URLs (for example: www.google.com) without these brackets.

Images

You are able to use drag and drop to insert an image from an image file or your web browser. You can modify the markdown source code by clicking on the image. A relative path will be used if the image that is added using drag and drop is in same directory or sub-directory as the document you’re currently editing.

Emphasis

Markdown treats asterisks ( * ) and underscores ( _ ) as indicators of emphasis. Text wrapped with one * or _ will be wrapped with an HTML tag. For example:

GFM will ignore underscores in words, which is commonly used in code and names, like this:

To produce a literal asterisk or underscore at a position where it would otherwise be used as an emphasis delimiter, you can backslash escape it with a backslash character:

Typora recommends using the * symbol.

Strong

A double * or _ will cause its enclosed contents to be wrapped with an HTML tag, e.g:

double asterisks

double underscores

Typora recommends using the ** symbol.

To indicate an inline span of code, wrap it with backtick quotes (`). Unlike a pre-formatted code block, a code span indicates code within a normal paragraph. For example:

Use the printf() function.

Strikethrough

GFM adds syntax to create strikethrough text, which is missing from standard Markdown.

becomes Mistaken text.

Emoji :happy:

Inline Math

To trigger inline preview for inline math: input “$”, then press the ESC key, then input a TeX command.

You can find more details here.

Subscript

To use this feature, please enable it first in the Markdown tab of the preference panel. Then, use

to wrap subscript content. For example: H

Superscript

Highlight

You can use HTML to style content what pure Markdown does not support. For example, use this text is red to add text with red color.

Underlines

Underline isn’t specified in Markdown of GFM, but can be produced by using underline HTML tags:

Underline becomes Underline.

Embed Contents

Some websites provide iframe-based embed code which you can also paste into Typora. For example:

Video

You can use the HTML tag to embed videos. For example:

Other HTML Support

You can find more details here.

Here is the text of the first footnote. ↩

Here is the text of the second footnote. ↩

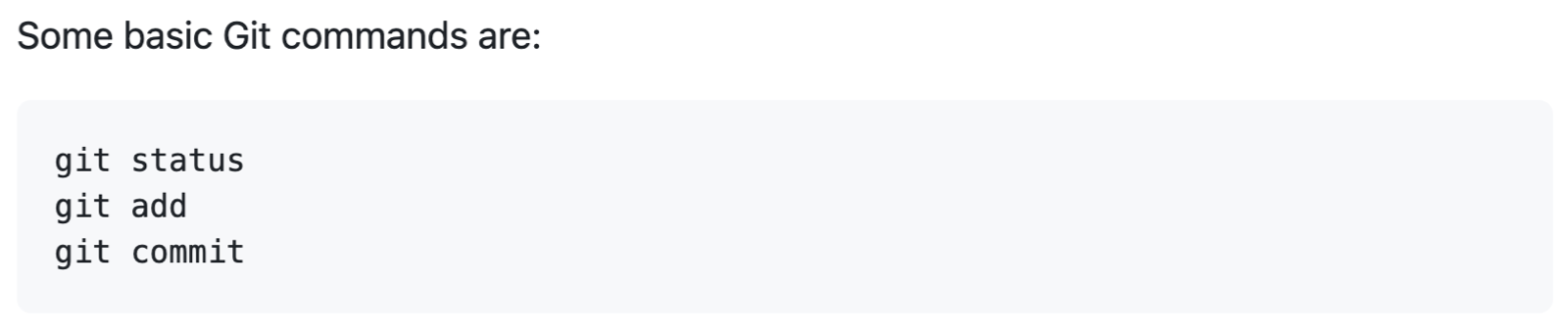

Creating and highlighting code blocks

In this article

Share samples of code with fenced code blocks and enabling syntax highlighting.

Fenced code blocks

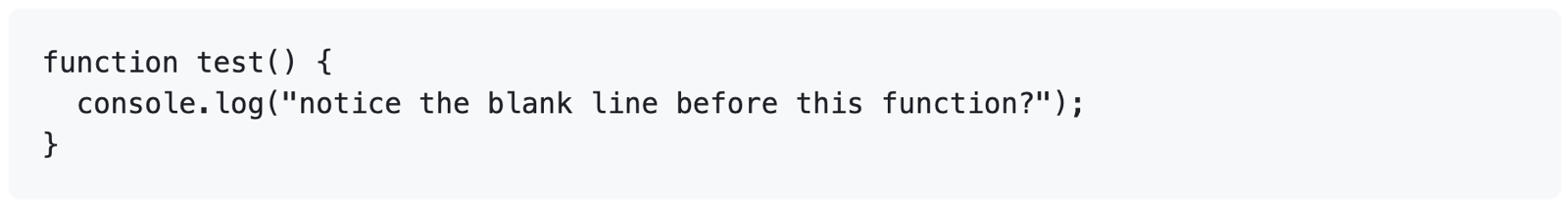

You can create fenced code blocks by placing triple backticks «` before and after the code block. We recommend placing a blank line before and after code blocks to make the raw formatting easier to read.

Tip: To preserve your formatting within a list, make sure to indent non-fenced code blocks by eight spaces.

To display triple backticks in a fenced code block, wrap them inside quadruple backticks.

If you are frequently editing code snippets and tables, you may benefit from enabling a fixed-width font in all comment fields on GitHub. For more information, see «Enabling fixed-width fonts in the editor.»

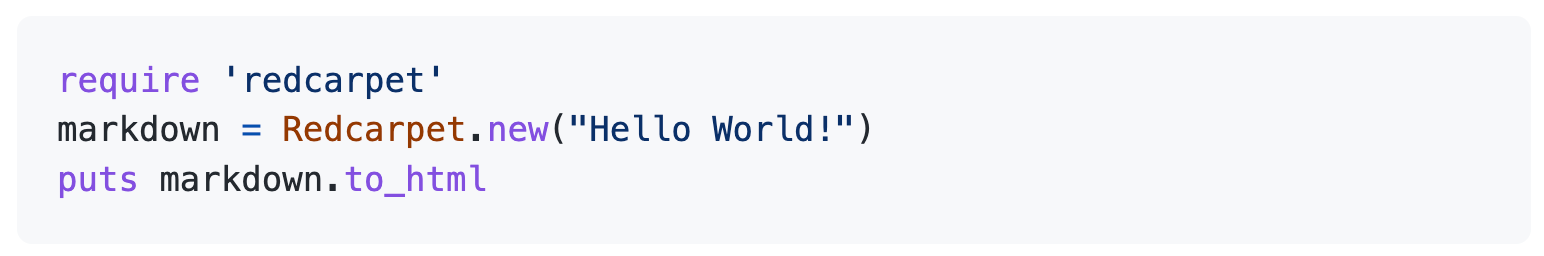

You can add an optional language identifier to enable syntax highlighting in your fenced code block.

For example, to syntax highlight Ruby code:

We use Linguist to perform language detection and to select third-party grammars for syntax highlighting. You can find out which keywords are valid in the languages YAML file.

You can also use code blocks to create diagrams in Markdown. GitHub supports Mermaid, GeoJSON, TopoJSON, and ASCII STL syntax. For more information, see «Creating diagrams.»

Help us make these docs great!

All GitHub docs are open source. See something that’s wrong or unclear? Submit a pull request.

Markdown Syntax

In different locations around Hub, you have the ability to format blocks of text. This formatting is applied using the Markdown markup syntax. Markdown is supported for the following features in Hub:

These widgets use Markdown to format text. These widgets can be placed on dashboards and project overview pages.

The project description that is shown on a project overview page is formatted in Markdown.

The agreement text that is presented to users who are required to accept an information notice to access Hub is formatted in Markdown.

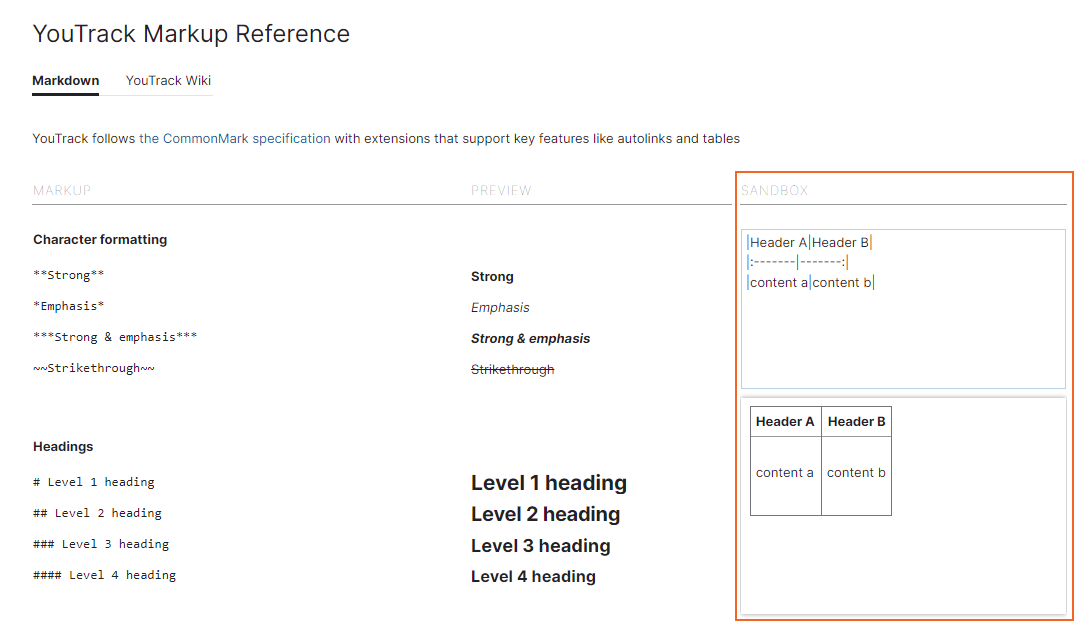

The Markdown implementation in YouTrack follows the CommonMark specification with extensions. These extensions support formatting options that are not included in the formal specification like strikethrough text, tables, and autolinks.

To see any of these formatting options in action, paste the sample block of code into an input field that accepts Markdown.

Character Formatting

You can format inline text with the following Markdown syntax.

Surround text with two asterisks ( ** ) or two underscore characters ( __ ).

Surround text with single asterisks ( * )or underscore characters ( _ ).

Surround text with two tildes (

Surround text with single backquotes ( ` ).

Surround text with single underscore characters or two tildes inside two asterisks. Surround text with three asterisks to apply strong emphasis.

— it wasn’t _that_ important. Let’s try a few `combinations`: **This text is strong,

this text is strong with strikethrough

, and _this text is formatted with strong emphasis_** ***This text is formatted with strong emphasis too.***

Headings

Hub also supports an alternative syntax for heading levels 1 and 2:

For heading level 1, enter one or more = characters on the following line.

Paragraphs and Line Breaks

Contiguous lines of text belong to the same paragraph. Use the following guidelines to structure your content into paragraphs and enter line breaks.

To start a new paragraph, leave a blank line between lines of text.

To start a new line inside a paragraph, enter two trailing spaces at the end of the line of text.

Thematic Breaks

Create sections in your content with horizontal lines. Use any of the following methods to add a horizontal line:

Three underscores ( ___ )

Block Quotes

Use block quotes to call special attention to a quote from another source. You can apply character formatting to inline text inside the quoted block.

To set text as a quote block, start the line with one or more > characters. Follow these characters with a space and enter the quoted text. The number of > signs determines the level of nesting inside the quote block.

If your quote spans multiple paragraphs, each blank line must start with the > character. This ensures that the entire quote block is grouped together.

Indented Code Blocks

You can format blocks of text in a monospaced font to make it easier to identify and read as code.

To format a code block in Markdown, indent every line of the block by at least four spaces. An indented code block cannot interrupt a paragraph, so you must insert at least one blank line between a paragraph the indented code block that follows. The input is processed is as follows:

One level of indentation (four spaces) is removed from each line of the code block.

The contents of the code block are literal text and are not parsed as Markdown.

Any non-blank line with fewer than four leading spaces ends the code block and starts a new paragraph.

Fenced Code Blocks

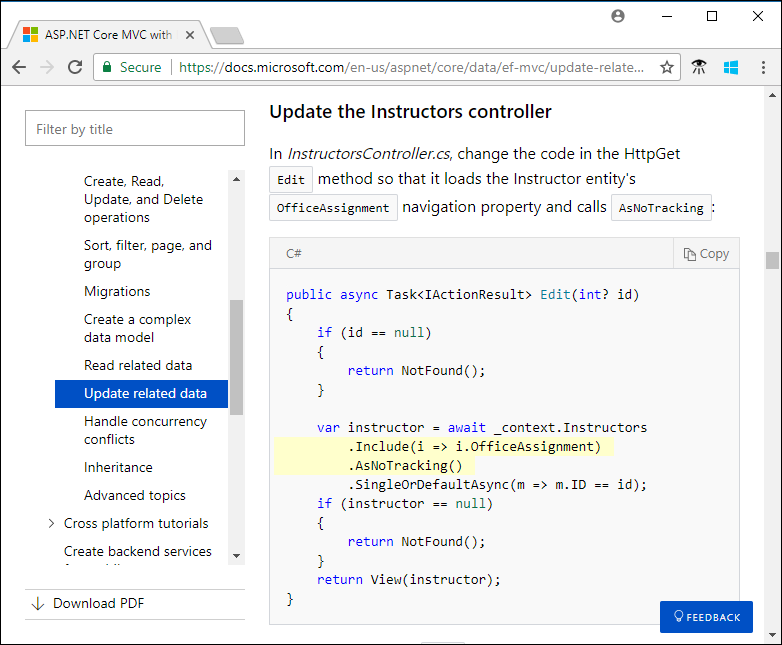

Unlike indented code blocks, fenced code blocks have an info string that lets you specify which language is used for syntax highlighting. Language-specific highlights make the code easier to read.

Syntax highlighting is supported for a range of languages. YouTrack detects and highlights code in C, C++, C#, Java, JavaScript, Perl, Python, Ruby, and SH automatically. To highlight code in other languages, set the language in the info string (the line with the opening code fence). The following languages are supported: apollo (AGC/AEA Assembly Language), basic, clj (Clojure) css, dart, erlang, hs (Haskell), kt (Kotlin), lisp, llvm, lua, matlab, ml, mumps, n (Nemerle), pascal, proto, scala, sql, tcl, tex, vb, vhdl, wiki, xq, and yaml.

To create a fenced code block that spans multiple lines of code, set the text inside three or more backquotes ( «` ) or tildes (

Open and close the block with the same character.

Use the same number of characters to open and close the code fence.

Lists

Use the following syntax to create lists:

To create an ordered list, start the line with a number and a period ( 1. ). Increment subsequent numbers to format each item in the ordered list.

To nest an unordered list inside an unordered or ordered list, indent the line with two spaces. Nesting ordered lists is not supported.

Tables

Tables are a great tool for adding structure to your content. Use the following syntax to create tables:

To create columns, use vertical bars ( | ). The outer bars are optional.

Note that the columns don’t have to line up perfectly in the raw Markdown. You can also add character formatting to text inside the table.

All of the cells are left-justified. The syntax that aligns text to the right or center is not supported.

Links

There are several ways to insert hyperlinks with Markdown.

Inline with tooltip

Use inline formatting and add the tooltip in quotation marks after the URL.

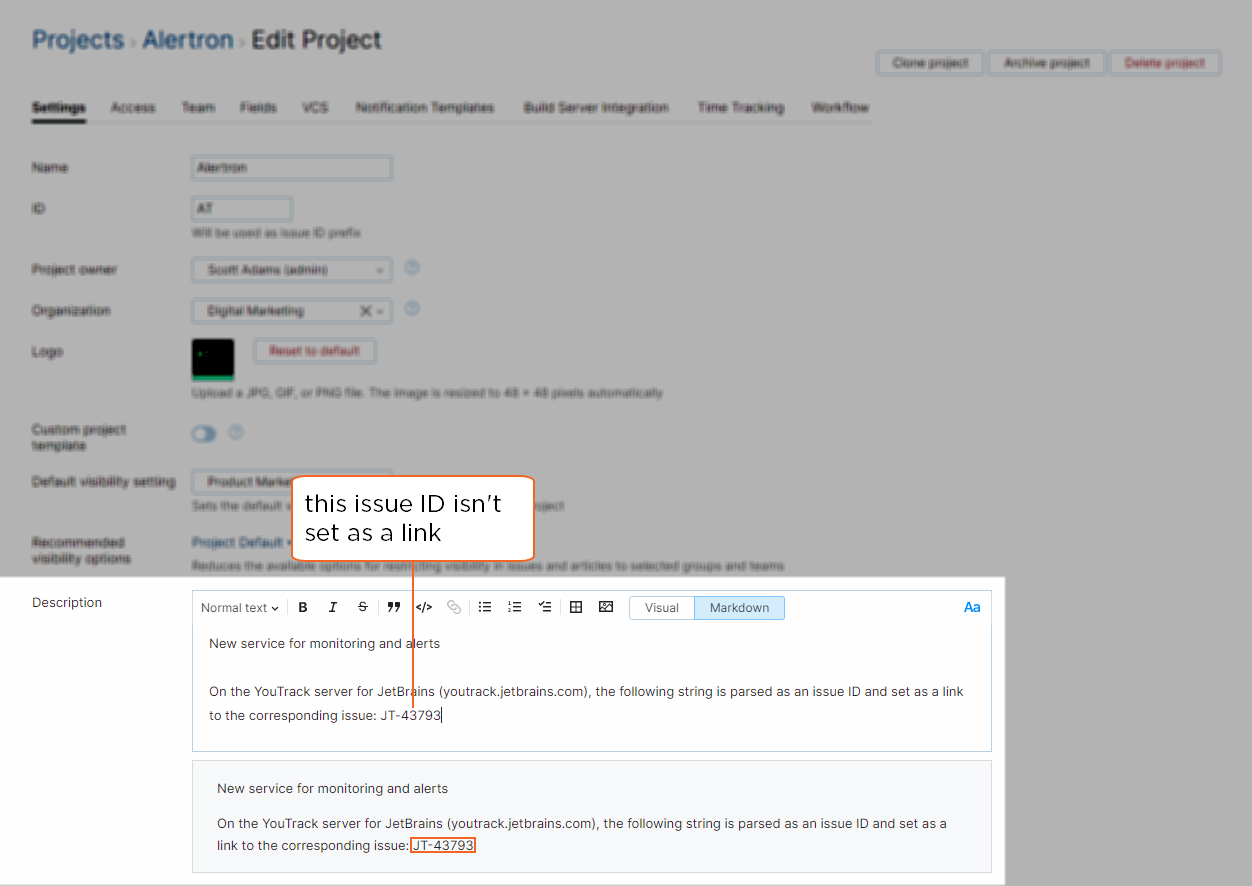

Hub has also extended the standard syntax to include autolinks.

URLs and URLs in angle brackets are automatically converted into hyperlinks. For example:

Autolinks

Autolinks are absolute URIs and email addresses that are set inside angle brackets ( ). They are parsed as links, with the URL or email address as the link label. Unlike links that let you specify link text and tooltips, this syntax simply converts the URL or email address into a clickable link.

Hub supports an extended syntax for URLs. Any string that is parsed as a URL is converted into a clickable link, even without the angle brackets. Email addresses that are not set inside angle brackets are displayed as text.

Images

The syntax for images is similar to the syntax for links. To insert an inline image:

Wrap the alt text with brackets ( [ ] ).

Set the image URL and tooltip in parentheses ( ( ) ).

You can also use the reference style for images. To insert an image reference:

Wrap the alt text with brackets ( [ ] ).

Set the image reference in brackets ( [ ] ).

Backslash Escapes

When you have characters that are parsed as Markdown that you want to show as written, you can escape the character with the backslash ( \ ).

Backslashes before non-markup characters are shown as backslash characters.

Escaped characters are treated as regular characters. Their usual meaning in Markdown syntax is ignored.

Backslash escapes do not work in fenced code blocks, inline code spans, or autolinks.

Markdown has support for code blocks. There are three ways to include A Markdown code block in your document:

In this article, I’ll demonstrate all three ways to include code in a Markdown document.

Markdown inline code block

For starters, Markdown allows you to include inline code in your document. Inline code is surrounded by backticks (`). For example:

Inline code is useful to mention a piece of code in a document. For example, you might want to mention the print function in a document like above. Most of the time, this code won’t be highlighted by the syntax highlighter, however.

Fenced code blocks

A fenced code block is a block of code that is surrounded by three backticks (“`) and an optional language specifier. In the most basic form, you can leave out the language specifier. For example:

Enable syntax highlighting

To enable syntax highlighting for your Markdown code block, you need to specify the language right after the first three backticks, like so:

Both examples above will be rendered as a code block in the document. If a language is specified like in the first example, the syntax highlighter will be enabled for the selected language.

For a list of commonly available languages, see to list at the bottom of this article.

Indented code blocks

If fenced code blocks are an option for your specific Markdown parser, I recommend using them because you can specify the language of the code block.

The most basic markdown syntax for indented code blocks is to start a line with four spaces. This will be rendered as a code block in the document and is supported by all Markdown parsers. For example:

The upside of this method is that it is supported by pretty much all Markdown parsers, as far as I know. However, there are some downsides to using indented code blocks as well:

If possible, I strongly suggest using fenced code blocks.

Markdown code block language list

Which languages are supported, heavily depends on the Markdown parser you’re using. What follows here, is a list of many common languages and formats that you can try. If your language isn’t in here, I suggest you simply try if it is supported. Alternatively, visit the documentation of your specific Markdown.

Here’s the list of commonly supported languages on sites like GitHub:

Learn more

Make sure to also check out my Markdown cheat sheet for a quick overview of what’s possible. You might also like to read more about including Markdown tables in your document, and my tricks to center stuff in Markdown.

Markdown Cheatsheet

Clone this wiki locally

This is intended as a quick reference and showcase. For more complete info, see John Gruber’s original spec and the Github-flavored Markdown info page.

Note that there is also a Cheatsheet specific to Markdown Here if that’s what you’re looking for. You can also check out more Markdown tools.

Table of Contents

Alternatively, for H1 and H2, an underline-ish style:

Emphasis, aka italics, with asterisks or underscores.

Strong emphasis, aka bold, with asterisks or underscores.

Combined emphasis with asterisks and underscores.

Strikethrough uses two tildes. Scratch this.

(In this example, leading and trailing spaces are shown with with dots: ⋅)

Actual numbers don’t matter, just that it’s a number

And another item.

You can have properly indented paragraphs within list items. Notice the blank line above, and the leading spaces (at least one, but we’ll use three here to also align the raw Markdown).

To have a line break without a paragraph, you will need to use two trailing spaces.

Note that this line is separate, but within the same paragraph.

(This is contrary to the typical GFM line break behaviour, where trailing spaces are not required.)

There are two ways to create links.

Or leave it empty and use the link text itself.

URLs and URLs in angle brackets will automatically get turned into links. http://www.example.com or http://www.example.com and sometimes example.com (but not on Github, for example).

Some text to show that the reference links can follow later.

Here’s our logo (hover to see the title text):

Code and Syntax Highlighting

Inline code has back-ticks around it.

Footnotes aren’t part of the core Markdown spec, but they supported by GFM.

Colons can be used to align columns.

| Tables | Are | Cool |

|---|---|---|

| col 3 is | right-aligned | $1600 |

| col 2 is | centered | $12 |

| zebra stripes | are neat | $1 |

There must be at least 3 dashes separating each header cell. The outer pipes (|) are optional, and you don’t need to make the raw Markdown line up prettily. You can also use inline Markdown.

| Markdown | Less | Pretty |

|---|---|---|

| Still | renders | nicely |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

Blockquotes are very handy in email to emulate reply text. This line is part of the same quote.

This is a very long line that will still be quoted properly when it wraps. Oh boy let’s keep writing to make sure this is long enough to actually wrap for everyone. Oh, you can put Markdown into a blockquote.

You can also use raw HTML in your Markdown, and it’ll mostly work pretty well.

Extended Syntax

Advanced features that build on the basic Markdown syntax.

Overview

The basic syntax outlined in the original Markdown design document added many of the elements needed on a day-to-day basis, but it wasn’t enough for some people. That’s where extended syntax comes in.

Several individuals and organizations took it upon themselves to extend the basic syntax by adding additional elements like tables, code blocks, syntax highlighting, URL auto-linking, and footnotes. These elements can be enabled by using a lightweight markup language that builds upon the basic Markdown syntax, or by adding an extension to a compatible Markdown processor.

Availability

Not all Markdown applications support extended syntax elements. You’ll need to check whether or not the lightweight markup language your application is using supports the extended syntax elements you want to use. If it doesn’t, it may still be possible to enable extensions in your Markdown processor.

Lightweight Markup Languages

There are several lightweight markup languages that are supersets of Markdown. They include basic syntax and build upon it by adding additional elements like tables, code blocks, syntax highlighting, URL auto-linking, and footnotes. Many of the most popular Markdown applications use one of the following lightweight markup languages:

Markdown Processors

There are dozens of Markdown processors available. Many of them allow you to add extensions that enable extended syntax elements. Check your processor’s documentation for more information.

Tables

The rendered output looks like this:

| Syntax | Description |

|---|---|

| Header | Title |

| Paragraph | Text |

Cell widths can vary, as shown below. The rendered output will look the same.

Alignment

You can align text in the columns to the left, right, or center by adding a colon ( : ) to the left, right, or on both side of the hyphens within the header row.

The rendered output looks like this:

| Syntax | Description | Test Text |

|---|---|---|

| Header | Title | Here’s this |

| Paragraph | Text | And more |

Formatting Text in Tables

You can format the text within tables. For example, you can add links, code (words or phrases in backticks ( ` ) only, not code blocks), and emphasis.

You can’t use headings, blockquotes, lists, horizontal rules, images, or most HTML tags.

Escaping Pipe Characters in Tables

You can display a pipe ( | ) character in a table by using its HTML character code ( | ).

Fenced Code Blocks

The basic Markdown syntax allows you to create code blocks by indenting lines by four spaces or one tab. If you find that inconvenient, try using fenced code blocks. Depending on your Markdown processor or editor, you’ll use three backticks ( «` ) or three tildes (

) on the lines before and after the code block. The best part? You don’t have to indent any lines!

The rendered output looks like this:

Syntax Highlighting

Many Markdown processors support syntax highlighting for fenced code blocks. This feature allows you to add color highlighting for whatever language your code was written in. To add syntax highlighting, specify a language next to the backticks before the fenced code block.

The rendered output looks like this:

Footnotes

Footnotes allow you to add notes and references without cluttering the body of the document. When you create a footnote, a superscript number with a link appears where you added the footnote reference. Readers can click the link to jump to the content of the footnote at the bottom of the page.

To create a footnote reference, add a caret and an identifier inside brackets ( [^1] ). Identifiers can be numbers or words, but they can’t contain spaces or tabs. Identifiers only correlate the footnote reference with the footnote itself — in the output, footnotes are numbered sequentially.

Add the footnote using another caret and number inside brackets with a colon and text ( [^1]: My footnote. ). You don’t have to put footnotes at the end of the document. You can put them anywhere except inside other elements like lists, block quotes, and tables.

The rendered output looks like this:

Here’s a simple footnote, 1 and here’s a longer one. 2

This is the first footnote. ↩

Here’s one with multiple paragraphs and code.

Indent paragraphs to include them in the footnote.

Add as many paragraphs as you like. ↩

Heading IDs

Many Markdown processors support custom IDs for headings — some Markdown processors automatically add them. Adding custom IDs allows you to link directly to headings and modify them with CSS. To add a custom heading ID, enclose the custom ID in curly braces on the same line as the heading.

The HTML looks like this:

Linking to Heading IDs

You can link to headings with custom IDs in the file by creating a standard link with a number sign ( # ) followed by the custom heading ID. These are commonly referred to as anchor links.

| Markdown | HTML | Rendered Output |

|---|---|---|

| [Heading IDs](#heading-ids) | Heading IDs | Heading IDs |

Other websites can link to the heading by adding the custom heading ID to the full URL of the webpage (e.g, [Heading IDs](https://www.markdownguide.org/extended-syntax#heading-ids) ).

Definition Lists

Some Markdown processors allow you to create definition lists of terms and their corresponding definitions. To create a definition list, type the term on the first line. On the next line, type a colon followed by a space and the definition.

The HTML looks like this:

The rendered output looks like this:

First Term This is the definition of the first term. Second Term This is one definition of the second term. This is another definition of the second term.

Strikethrough

) before and after the words.

The rendered output looks like this:

The world is flat. We now know that the world is round.

Task Lists

The rendered output looks like this:

Emoji

There are two ways to add emoji to Markdown files: copy and paste the emoji into your Markdown-formatted text, or type emoji shortcodes.

Copying and Pasting Emoji

In most cases, you can simply copy an emoji from a source like Emojipedia and paste it into your document. Many Markdown applications will automatically display the emoji in the Markdown-formatted text. The HTML and PDF files you export from your Markdown application should display the emoji.

Using Emoji Shortcodes

Some Markdown applications allow you to insert emoji by typing emoji shortcodes. These begin and end with a colon and include the name of an emoji.

The rendered output looks like this:

Gone camping! ⛺ Be back soon.

That is so funny! 😂

Highlight

The rendered output looks like this:

Alternatively, if your Markdown application supports HTML, you can use the mark HTML tag.

Subscript

This isn’t common, but some Markdown processors allow you to use subscript to position one or more characters slightly below the normal line of type. To create a subscript, use one tilde symbol (

) before and after the characters.

The rendered output looks like this:

Alternatively, if your Markdown application supports HTML, you can use the sub HTML tag.

Superscript

This isn’t common, but some Markdown processors allow you to use superscript to position one or more characters slightly above the normal line of type. To create a superscript, use one caret symbol ( ^ ) before and after the characters.

The rendered output looks like this:

Alternatively, if your Markdown application supports HTML, you can use the sup HTML tag.

Automatic URL Linking

Many Markdown processors automatically turn URLs into links. That means if you type http://www.example.com, your Markdown processor will automatically turn it into a link even though you haven’t used brackets.

The rendered output looks like this:

Disabling Automatic URL Linking

If you don’t want a URL to be automatically linked, you can remove the link by denoting the URL as code with backticks.

The rendered output looks like this:

Take your Markdown skills to the next level.

Learn Markdown in 60 pages. Designed for both novices and experts, The Markdown Guide book is a comprehensive reference that has everything you need to get started and master Markdown syntax.

Want to learn more Markdown?

Don’t stop now! 🚀 Star the GitHub repository and then enter your email address below to receive new Markdown tutorials via email. No spam!

Basic writing and formatting syntax

In this article

Create sophisticated formatting for your prose and code on GitHub with simple syntax.

To create a heading, add one to six # symbols before your heading text. The number of # you use will determine the size of the heading.

When you use two or more headings, GitHub automatically generates a table of contents which you can access by clicking

within the file header. Each heading title is listed in the table of contents and you can click a title to navigate to the selected section.

| Style | Syntax | Keyboard shortcut | Example | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bold | ** ** or __ __ | Command + B (Mac) or Ctrl + B (Windows/Linux) | **This is bold text** | This is bold text |

| Italic | * * or _ _ | Command + I (Mac) or Ctrl + I (Windows/Linux) | *This text is italicized* | This text is italicized |

| Strikethrough | This was mistaken text | |||

| Bold and nested italic | ** ** and _ _ | **This text is _extremely_ important** | This text is extremely important | |

| All bold and italic | *** *** | ***All this text is important*** | All this text is important | |

| Subscript | This is a subscript text | This is a subscript text | ||

| Superscript | This is a superscript text | This is a superscript text |

, then Quote reply. For more information about keyboard shortcuts, see «Keyboard shortcuts.»

You can call out code or a command within a sentence with single backticks. The text within the backticks will not be formatted. You can also press the Command + E (Mac) or Ctrl + E (Windows/Linux) keyboard shortcut to insert the backticks for a code block within a line of Markdown.

To format code or text into its own distinct block, use triple backticks.

If you are frequently editing code snippets and tables, you may benefit from enabling a fixed-width font in all comment fields on GitHub. For more information, see «Enabling fixed-width fonts in the editor.»

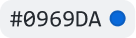

Supported color models

In issues, pull requests, and discussions, you can call out colors within a sentence by using backticks. A supported color model within backticks will display a visualization of the color.

Here are the currently supported color models.

| Color | Syntax | Example | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEX | `#RRGGBB` | `#0969DA` |  |

| RGB | `rgb(R,G,B)` | `rgb(9, 105, 218)` |  |

| HSL | `hsl(H,S,L)` | `hsl(212, 92%, 45%)` |  |

Notes:

This site was built using [GitHub Pages](https://pages.github.com/).

Tip: GitHub automatically creates links when valid URLs are written in a comment. For more information, see «Autolinked references and URLs.»

You can link directly to a section in a rendered file by hovering over the section heading to expose the link:

You can define relative links and image paths in your rendered files to help readers navigate to other files in your repository.

A relative link is a link that is relative to the current file. For example, if you have a README file in root of your repository, and you have another file in docs/CONTRIBUTING.md, the relative link to CONTRIBUTING.md in your README might look like this:

Tip: When you want to display an image which is in your repository, you should use relative links instead of absolute links.

Here are some examples for using relative links to display an image.

Note: The last two relative links in the table above will work for images in a private repository only if the viewer has at least read access to the private repository which contains these images.

For more information, see «Relative Links.»

Specifying the theme an image is shown to

You can specify the theme an image is displayed for in Markdown by using the HTML

element in combination with the prefers-color-scheme media feature. We distinguish between light and dark color modes, so there are two options available. You can use these options to display images optimized for dark or light backgrounds. This is particularly helpful for transparent PNG images.

For example, the following code displays a sun image for light themes and a moon for dark themes:

The old method of specifying images based on the theme, by using a fragment appended to the URL ( #gh-dark-mode-only or #gh-light-mode-only ), is deprecated and will be removed in favor of the new method described above.

To order your list, precede each line with a number.

You can create a nested list by indenting one or more list items below another item.

Note: In the web-based editor, you can indent or dedent one or more lines of text by first highlighting the desired lines and then using Tab or Shift + Tab respectively.

To create a nested list in the comment editor on GitHub, which doesn’t use a monospaced font, you can look at the list item immediately above the nested list and count the number of characters that appear before the content of the item. Then type that number of space characters in front of the nested list item.

If a task list item description begins with a parenthesis, you’ll need to escape it with \ :

— [ ] \(Optional) Open a followup issue

For more information, see «About task lists.»

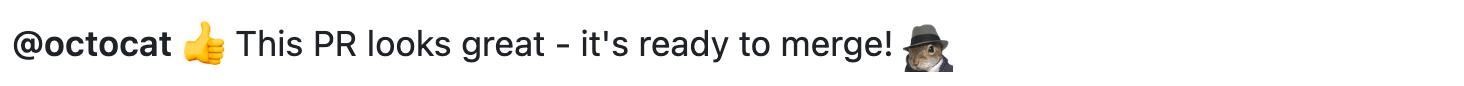

Mentioning people and teams

You can mention a person or team on GitHub by typing @ plus their username or team name. This will trigger a notification and bring their attention to the conversation. People will also receive a notification if you edit a comment to mention their username or team name. For more information about notifications, see «About notifications.»

Note: A person will only be notified about a mention if the person has read access to the repository and, if the repository is owned by an organization, the person is a member of the organization.

@github/support What do you think about these updates?

When you mention a parent team, members of its child teams also receive notifications, simplifying communication with multiple groups of people. For more information, see «About teams.»

Typing an @ symbol will bring up a list of people or teams on a project. The list filters as you type, so once you find the name of the person or team you are looking for, you can use the arrow keys to select it and press either tab or enter to complete the name. For teams, enter the @organization/team-name and all members of that team will get subscribed to the conversation.

The autocomplete results are restricted to repository collaborators and any other participants on the thread.

Referencing issues and pull requests

Referencing external resources

If custom autolink references are configured for a repository, then references to external resources, like a JIRA issue or Zendesk ticket, convert into shortened links. To know which autolinks are available in your repository, contact someone with admin permissions to the repository. For more information, see «Configuring autolinks to reference external resources.»

Typing : will bring up a list of suggested emoji. The list will filter as you type, so once you find the emoji you’re looking for, press Tab or Enter to complete the highlighted result.

For a full list of available emoji and codes, check out the Emoji-Cheat-Sheet.

You can create a new paragraph by leaving a blank line between lines of text.

You can add footnotes to your content by using this bracket syntax:

The footnote will render like this:

Note: The position of a footnote in your Markdown does not influence where the footnote will be rendered. You can write a footnote right after your reference to the footnote, and the footnote will still render at the bottom of the Markdown.

Footnotes are not supported in wikis.

Hiding content with comments

You can tell GitHub to hide content from the rendered Markdown by placing the content in an HTML comment.

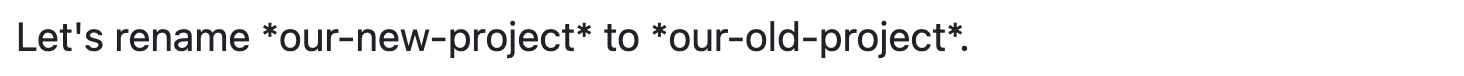

Ignoring Markdown formatting

You can tell GitHub to ignore (or escape) Markdown formatting by using \ before the Markdown character.

Let’s rename \*our-new-project\* to \*our-old-project\*.

For more information, see Daring Fireball’s «Markdown Syntax.»

Disabling Markdown rendering

When viewing a Markdown file, you can click

at the top of the file to disable Markdown rendering and view the file’s source instead.

Disabling Markdown rendering enables you to use source view features, such as line linking, which is not possible when viewing rendered Markdown files.

Help us make these docs great!

All GitHub docs are open source. See something that’s wrong or unclear? Submit a pull request.

gdenning / gist:1134759

Note: This document is itself written using Markdown; you can see the source for it by adding ‘.text’ to the URL.

Markdown is intended to be as easy-to-read and easy-to-write as is feasible.

To this end, Markdown’s syntax is comprised entirely of punctuation characters, which punctuation characters have been carefully chosen so as to look like what they mean. E.g., asterisks around a word actually look like *emphasis*. Markdown lists look like, well, lists. Even blockquotes look like quoted passages of text, assuming you’ve ever used email.

Markdown’s syntax is intended for one purpose: to be used as a format for writing for the web.

Markdown is not a replacement for HTML, or even close to it. Its syntax is very small, corresponding only to a very small subset of HTML tags. The idea is not to create a syntax that makes it easier to insert HTML tags. In my opinion, HTML tags are already easy to insert. The idea for Markdown is to make it easy to read, write, and edit prose. HTML is a publishing format; Markdown is a writing format. Thus, Markdown’s formatting syntax only addresses issues that can be conveyed in plain text.

For any markup that is not covered by Markdown’s syntax, you simply use HTML itself. There’s no need to preface it or delimit it to indicate that you’re switching from Markdown to HTML; you just use the tags.

Note that Markdown formatting syntax is not processed within block-level HTML tags. E.g., you can’t use Markdown-style *emphasis* inside an HTML block.

Unlike block-level HTML tags, Markdown syntax is processed within span-level tags.

Automatic Escaping for Special Characters

Ampersands in particular are bedeviling for web writers. If you want to write about ‘AT&T’, you need to write ‘ AT&T ‘. You even need to escape ampersands within URLs. Thus, if you want to link to:

you need to encode the URL as:

in your anchor tag href attribute. Needless to say, this is easy to forget, and is probably the single most common source of HTML validation errors in otherwise well-marked-up web sites.

So, if you want to include a copyright symbol in your article, you can write:

and Markdown will leave it alone. But if you write:

Markdown will translate it to:

Similarly, because Markdown supports inline HTML, if you use angle brackets as delimiters for HTML tags, Markdown will treat them as such. But if you write:

Markdown will translate it to:

However, inside Markdown code spans and blocks, angle brackets and ampersands are always encoded automatically. This makes it easy to use Markdown to write about HTML code. (As opposed to raw HTML, which is a terrible format for writing about HTML syntax, because every single and & in your example code needs to be escaped.)

Paragraphs and Line Breaks

The implication of the «one or more consecutive lines of text» rule is that Markdown supports «hard-wrapped» text paragraphs. This differs significantly from most other text-to-HTML formatters (including Movable Type’s «Convert Line Breaks» option) which translate every line break character in a paragraph into a

tag.

When you do want to insert a

break tag using Markdown, you end a line with two or more spaces, then type return.

Markdown supports two styles of headers, [Setext] 1 and [atx] 2.

Setext-style headers are «underlined» using equal signs (for first-level headers) and dashes (for second-level headers). For example:

Atx-style headers use 1-6 hash characters at the start of the line, corresponding to header levels 1-6. For example:

Markdown uses email-style > characters for blockquoting. If you’re familiar with quoting passages of text in an email message, then you know how to create a blockquote in Markdown. It looks best if you hard wrap the text and put a > before every line:

Markdown allows you to be lazy and only put the > before the first line of a hard-wrapped paragraph:

Blockquotes can be nested (i.e. a blockquote-in-a-blockquote) by adding additional levels of > :

Blockquotes can contain other Markdown elements, including headers, lists, and code blocks:

Any decent text editor should make email-style quoting easy. For example, with BBEdit, you can make a selection and choose Increase Quote Level from the Text menu.

Markdown supports ordered (numbered) and unordered (bulleted) lists.

is equivalent to:

Ordered lists use numbers followed by periods:

It’s important to note that the actual numbers you use to mark the list have no effect on the HTML output Markdown produces. The HTML Markdown produces from the above list is:

If you instead wrote the list in Markdown like this:

you’d get the exact same HTML output. The point is, if you want to, you can use ordinal numbers in your ordered Markdown lists, so that the numbers in your source match the numbers in your published HTML. But if you want to be lazy, you don’t have to.

If you do use lazy list numbering, however, you should still start the list with the number 1. At some point in the future, Markdown may support starting ordered lists at an arbitrary number.

List markers typically start at the left margin, but may be indented by up to three spaces. List markers must be followed by one or more spaces or a tab.

To make lists look nice, you can wrap items with hanging indents:

But if you want to be lazy, you don’t have to:

If list items are separated by blank lines, Markdown will wrap the items in

tags in the HTML output. For example, this input:

List items may consist of multiple paragraphs. Each subsequent paragraph in a list item must be indented by either 4 spaces or one tab:

It looks nice if you indent every line of the subsequent paragraphs, but here again, Markdown will allow you to be lazy:

To put a blockquote within a list item, the blockquote’s > delimiters need to be indented:

It’s worth noting that it’s possible to trigger an ordered list by accident, by writing something like this:

In other words, a number-period-space sequence at the beginning of a line. To avoid this, you can backslash-escape the period:

Pre-formatted code blocks are used for writing about programming or markup source code. Rather than forming normal paragraphs, the lines of a code block are interpreted literally. Markdown wraps a code block in both

Markdown will generate:

A code block continues until it reaches a line that is not indented (or the end of the article).

Regular Markdown syntax is not processed within code blocks. E.g., asterisks are just literal asterisks within a code block. This means it’s also easy to use Markdown to write about Markdown’s own syntax.

You can produce a horizontal rule tag ( ) by placing three or more hyphens, asterisks, or underscores on a line by themselves. If you wish, you may use spaces between the hyphens or asterisks. Each of the following lines will produce a horizontal rule:

Markdown supports two style of links: inline and reference.

In both styles, the link text is delimited by [square brackets].

To create an inline link, use a set of regular parentheses immediately after the link text’s closing square bracket. Inside the parentheses, put the URL where you want the link to point, along with an optional title for the link, surrounded in quotes. For example:

If you’re referring to a local resource on the same server, you can use relative paths:

Reference-style links use a second set of square brackets, inside which you place a label of your choosing to identify the link:

You can optionally use a space to separate the sets of brackets:

Then, anywhere in the document, you define your link label like this, on a line by itself:

The following three link definitions are equivalent:

Note: There is a known bug in Markdown.pl 1.0.1 which prevents single quotes from being used to delimit link titles.

The link URL may, optionally, be surrounded by angle brackets:

You can put the title attribute on the next line and use extra spaces or tabs for padding, which tends to look better with longer URLs:

Link definitions are only used for creating links during Markdown processing, and are stripped from your document in the HTML output.

And then define the link:

Because link names may contain spaces, this shortcut even works for multiple words in the link text:

And then define the link:

Link definitions can be placed anywhere in your Markdown document. I tend to put them immediately after each paragraph in which they’re used, but if you want, you can put them all at the end of your document, sort of like footnotes.

Here’s an example of reference links in action:

Using the implicit link name shortcut, you could instead write:

Both of the above examples will produce the following HTML output:

For comparison, here is the same paragraph written using Markdown’s inline link style:

The point of reference-style links is not that they’re easier to write. The point is that with reference-style links, your document source is vastly more readable. Compare the above examples: using reference-style links, the paragraph itself is only 81 characters long; with inline-style links, it’s 176 characters; and as raw HTML, it’s 234 characters. In the raw HTML, there’s more markup than there is text.

With Markdown’s reference-style links, a source document much more closely resembles the final output, as rendered in a browser. By allowing you to move the markup-related metadata out of the paragraph, you can add links without interrupting the narrative flow of your prose.

Markdown treats asterisks ( * ) and underscores ( _ ) as indicators of emphasis. Text wrapped with one * or _ will be wrapped with an HTML tag; double * ‘s or _ ‘s will be wrapped with an HTML tag. E.g., this input:

You can use whichever style you prefer; the lone restriction is that the same character must be used to open and close an emphasis span.

Emphasis can be used in the middle of a word:

But if you surround an * or _ with spaces, it’ll be treated as a literal asterisk or underscore.

To produce a literal asterisk or underscore at a position where it would otherwise be used as an emphasis delimiter, you can backslash escape it:

To indicate a span of code, wrap it with backtick quotes ( ` ). Unlike a pre-formatted code block, a code span indicates code within a normal paragraph. For example:

To include a literal backtick character within a code span, you can use multiple backticks as the opening and closing delimiters:

which will produce this:

With a code span, ampersands and angle brackets are encoded as HTML entities automatically, which makes it easy to include example HTML tags. Markdown will turn this:

You can write this:

Admittedly, it’s fairly difficult to devise a «natural» syntax for placing images into a plain text document format.

Markdown uses an image syntax that is intended to resemble the syntax for links, allowing for two styles: inline and reference.

Inline image syntax looks like this:

Reference-style image syntax looks like this:

Where «id» is the name of a defined image reference. Image references are defined using syntax identical to link references:

As of this writing, Markdown has no syntax for specifying the dimensions of an image; if this is important to you, you can simply use regular HTML tags.

Markdown supports a shortcut style for creating «automatic» links for URLs and email addresses: simply surround the URL or email address with angle brackets. What this means is that if you want to show the actual text of a URL or email address, and also have it be a clickable link, you can do this:

Markdown will turn this into:

Automatic links for email addresses work similarly, except that Markdown will also perform a bit of randomized decimal and hex entity-encoding to help obscure your address from address-harvesting spambots. For example, Markdown will turn this:

into something like this:

which will render in a browser as a clickable link to «address@example.com».

(This sort of entity-encoding trick will indeed fool many, if not most, address-harvesting bots, but it definitely won’t fool all of them. It’s better than nothing, but an address published in this way will probably eventually start receiving spam.)

Markdown allows you to use backslash escapes to generate literal characters which would otherwise have special meaning in Markdown’s formatting syntax. For example, if you wanted to surround a word with literal asterisks (instead of an HTML tag), you can use backslashes before the asterisks, like this:

Markdown provides backslash escapes for the following characters:

Markdown: Syntax

Note: This document is itself written using Markdown; you can see the source for it by adding ‘.text’ to the URL.

Overview

Philosophy

Markdown is intended to be as easy-to-read and easy-to-write as is feasible.

Readability, however, is emphasized above all else. A Markdown-formatted document should be publishable as-is, as plain text, without looking like it’s been marked up with tags or formatting instructions. While Markdown’s syntax has been influenced by several existing text-to-HTML filters — including Setext, atx, Textile, reStructuredText, Grutatext, and EtText — the single biggest source of inspiration for Markdown’s syntax is the format of plain text email.

To this end, Markdown’s syntax is comprised entirely of punctuation characters, which punctuation characters have been carefully chosen so as to look like what they mean. E.g., asterisks around a word actually look like *emphasis*. Markdown lists look like, well, lists. Even blockquotes look like quoted passages of text, assuming you’ve ever used email.

Inline HTML

Markdown’s syntax is intended for one purpose: to be used as a format for writing for the web.

Markdown is not a replacement for HTML, or even close to it. Its syntax is very small, corresponding only to a very small subset of HTML tags. The idea is not to create a syntax that makes it easier to insert HTML tags. In my opinion, HTML tags are already easy to insert. The idea for Markdown is to make it easy to read, write, and edit prose. HTML is a publishing format; Markdown is a writing format. Thus, Markdown’s formatting syntax only addresses issues that can be conveyed in plain text.

For any markup that is not covered by Markdown’s syntax, you simply use HTML itself. There’s no need to preface it or delimit it to indicate that you’re switching from Markdown to HTML; you just use the tags.

The only restrictions are that block-level HTML elements — e.g.

Note that Markdown formatting syntax is not processed within block-level HTML tags. E.g., you can’t use Markdown-style *emphasis* inside an HTML block.

Unlike block-level HTML tags, Markdown syntax is processed within span-level tags.

Automatic Escaping for Special Characters

Ampersands in particular are bedeviling for web writers. If you want to write about ‘AT&T’, you need to write ‘ AT&T ’. You even need to escape ampersands within URLs. Thus, if you want to link to:

you need to encode the URL as:

in your anchor tag href attribute. Needless to say, this is easy to forget, and is probably the single most common source of HTML validation errors in otherwise well-marked-up web sites.

So, if you want to include a copyright symbol in your article, you can write:

and Markdown will leave it alone. But if you write:

Markdown will translate it to:

Similarly, because Markdown supports inline HTML, if you use angle brackets as delimiters for HTML tags, Markdown will treat them as such. But if you write:

Markdown will translate it to:

However, inside Markdown code spans and blocks, angle brackets and ampersands are always encoded automatically. This makes it easy to use Markdown to write about HTML code. (As opposed to raw HTML, which is a terrible format for writing about HTML syntax, because every single and & in your example code needs to be escaped.)

Block Elements

Paragraphs and Line Breaks

A paragraph is simply one or more consecutive lines of text, separated by one or more blank lines. (A blank line is any line that looks like a blank line — a line containing nothing but spaces or tabs is considered blank.) Normal paragraphs should not be indented with spaces or tabs.

The implication of the “one or more consecutive lines of text” rule is that Markdown supports “hard-wrapped” text paragraphs. This differs significantly from most other text-to-HTML formatters (including Movable Type’s “Convert Line Breaks” option) which translate every line break character in a paragraph into a

tag.

When you do want to insert a

break tag using Markdown, you end a line with two or more spaces, then type return.

Yes, this takes a tad more effort to create a

, but a simplistic “every line break is a

” rule wouldn’t work for Markdown. Markdown’s email-style blockquoting and multi-paragraph list items work best — and look better — when you format them with hard breaks.

Headers

Markdown supports two styles of headers, Setext and atx.

Setext-style headers are “underlined” using equal signs (for first-level headers) and dashes (for second-level headers). For example:

Atx-style headers use 1-6 hash characters at the start of the line, corresponding to header levels 1-6. For example:

Optionally, you may “close” atx-style headers. This is purely cosmetic — you can use this if you think it looks better. The closing hashes don’t even need to match the number of hashes used to open the header. (The number of opening hashes determines the header level.) :

Blockquotes

Markdown uses email-style > characters for blockquoting. If you’re familiar with quoting passages of text in an email message, then you know how to create a blockquote in Markdown. It looks best if you hard wrap the text and put a > before every line:

Markdown allows you to be lazy and only put the > before the first line of a hard-wrapped paragraph:

Blockquotes can be nested (i.e. a blockquote-in-a-blockquote) by adding additional levels of > :

Blockquotes can contain other Markdown elements, including headers, lists, and code blocks:

Any decent text editor should make email-style quoting easy. For example, with BBEdit, you can make a selection and choose Increase Quote Level from the Text menu.

Lists

Markdown supports ordered (numbered) and unordered (bulleted) lists.

Unordered lists use asterisks, pluses, and hyphens — interchangably — as list markers:

is equivalent to:

Ordered lists use numbers followed by periods:

It’s important to note that the actual numbers you use to mark the list have no effect on the HTML output Markdown produces. The HTML Markdown produces from the above list is:

If you instead wrote the list in Markdown like this:

you’d get the exact same HTML output. The point is, if you want to, you can use ordinal numbers in your ordered Markdown lists, so that the numbers in your source match the numbers in your published HTML. But if you want to be lazy, you don’t have to.

If you do use lazy list numbering, however, you should still start the list with the number 1. At some point in the future, Markdown may support starting ordered lists at an arbitrary number.

List markers typically start at the left margin, but may be indented by up to three spaces. List markers must be followed by one or more spaces or a tab.

To make lists look nice, you can wrap items with hanging indents:

But if you want to be lazy, you don’t have to:

If list items are separated by blank lines, Markdown will wrap the items in

tags in the HTML output. For example, this input:

List items may consist of multiple paragraphs. Each subsequent paragraph in a list item must be indented by either 4 spaces or one tab:

It looks nice if you indent every line of the subsequent paragraphs, but here again, Markdown will allow you to be lazy:

To put a blockquote within a list item, the blockquote’s > delimiters need to be indented:

To put a code block within a list item, the code block needs to be indented twice — 8 spaces or two tabs:

It’s worth noting that it’s possible to trigger an ordered list by accident, by writing something like this:

In other words, a number-period-space sequence at the beginning of a line. To avoid this, you can backslash-escape the period:

Code Blocks

Pre-formatted code blocks are used for writing about programming or markup source code. Rather than forming normal paragraphs, the lines of a code block are interpreted literally. Markdown wraps a code block in both

Markdown will generate:

One level of indentation — 4 spaces or 1 tab — is removed from each line of the code block. For example, this:

A code block continues until it reaches a line that is not indented (or the end of the article).

Within a code block, ampersands ( & ) and angle brackets ( and > ) are automatically converted into HTML entities. This makes it very easy to include example HTML source code using Markdown — just paste it and indent it, and Markdown will handle the hassle of encoding the ampersands and angle brackets. For example, this:

Regular Markdown syntax is not processed within code blocks. E.g., asterisks are just literal asterisks within a code block. This means it’s also easy to use Markdown to write about Markdown’s own syntax.

Horizontal Rules

You can produce a horizontal rule tag ( ) by placing three or more hyphens, asterisks, or underscores on a line by themselves. If you wish, you may use spaces between the hyphens or asterisks. Each of the following lines will produce a horizontal rule:

Span Elements

Links

Markdown supports two style of links: inline and reference.

In both styles, the link text is delimited by [square brackets].

To create an inline link, use a set of regular parentheses immediately after the link text’s closing square bracket. Inside the parentheses, put the URL where you want the link to point, along with an optional title for the link, surrounded in quotes. For example:

If you’re referring to a local resource on the same server, you can use relative paths:

Reference-style links use a second set of square brackets, inside which you place a label of your choosing to identify the link:

You can optionally use a space to separate the sets of brackets:

Then, anywhere in the document, you define your link label like this, on a line by itself:

The following three link definitions are equivalent:

Note: There is a known bug in Markdown.pl 1.0.1 which prevents single quotes from being used to delimit link titles.

The link URL may, optionally, be surrounded by angle brackets:

You can put the title attribute on the next line and use extra spaces or tabs for padding, which tends to look better with longer URLs:

Link definitions are only used for creating links during Markdown processing, and are stripped from your document in the HTML output.

Link definition names may consist of letters, numbers, spaces, and punctuation — but they are not case sensitive. E.g. these two links:

The implicit link name shortcut allows you to omit the name of the link, in which case the link text itself is used as the name. Just use an empty set of square brackets — e.g., to link the word “Google” to the google.com web site, you could simply write:

And then define the link:

Because link names may contain spaces, this shortcut even works for multiple words in the link text:

And then define the link:

Link definitions can be placed anywhere in your Markdown document. I tend to put them immediately after each paragraph in which they’re used, but if you want, you can put them all at the end of your document, sort of like footnotes.

Here’s an example of reference links in action:

Using the implicit link name shortcut, you could instead write:

Both of the above examples will produce the following HTML output:

For comparison, here is the same paragraph written using Markdown’s inline link style:

The point of reference-style links is not that they’re easier to write. The point is that with reference-style links, your document source is vastly more readable. Compare the above examples: using reference-style links, the paragraph itself is only 81 characters long; with inline-style links, it’s 176 characters; and as raw HTML, it’s 234 characters. In the raw HTML, there’s more markup than there is text.

With Markdown’s reference-style links, a source document much more closely resembles the final output, as rendered in a browser. By allowing you to move the markup-related metadata out of the paragraph, you can add links without interrupting the narrative flow of your prose.

Emphasis

Markdown treats asterisks ( * ) and underscores ( _ ) as indicators of emphasis. Text wrapped with one * or _ will be wrapped with an HTML tag; double * ’s or _ ’s will be wrapped with an HTML tag. E.g., this input:

You can use whichever style you prefer; the lone restriction is that the same character must be used to open and close an emphasis span.

Emphasis can be used in the middle of a word:

But if you surround an * or _ with spaces, it’ll be treated as a literal asterisk or underscore.

To produce a literal asterisk or underscore at a position where it would otherwise be used as an emphasis delimiter, you can backslash escape it:

To indicate a span of code, wrap it with backtick quotes ( ` ). Unlike a pre-formatted code block, a code span indicates code within a normal paragraph. For example:

To include a literal backtick character within a code span, you can use multiple backticks as the opening and closing delimiters:

which will produce this:

The backtick delimiters surrounding a code span may include spaces — one after the opening, one before the closing. This allows you to place literal backtick characters at the beginning or end of a code span:

With a code span, ampersands and angle brackets are encoded as HTML entities automatically, which makes it easy to include example HTML tags. Markdown will turn this:

You can write this:

Images

Admittedly, it’s fairly difficult to devise a “natural” syntax for placing images into a plain text document format.

Markdown uses an image syntax that is intended to resemble the syntax for links, allowing for two styles: inline and reference.

Inline image syntax looks like this:

Reference-style image syntax looks like this:

Where “id” is the name of a defined image reference. Image references are defined using syntax identical to link references:

As of this writing, Markdown has no syntax for specifying the dimensions of an image; if this is important to you, you can simply use regular HTML tags.

Miscellaneous

Automatic Links

Markdown supports a shortcut style for creating “automatic” links for URLs and email addresses: simply surround the URL or email address with angle brackets. What this means is that if you want to show the actual text of a URL or email address, and also have it be a clickable link, you can do this:

Markdown will turn this into:

Automatic links for email addresses work similarly, except that Markdown will also perform a bit of randomized decimal and hex entity-encoding to help obscure your address from address-harvesting spambots. For example, Markdown will turn this:

into something like this:

which will render in a browser as a clickable link to “[email protected]”.

(This sort of entity-encoding trick will indeed fool many, if not most, address-harvesting bots, but it definitely won’t fool all of them. It’s better than nothing, but an address published in this way will probably eventually start receiving spam.)

Backslash Escapes

Markdown allows you to use backslash escapes to generate literal characters which would otherwise have special meaning in Markdown’s formatting syntax. For example, if you wanted to surround a word with literal asterisks (instead of an HTML tag), you can use backslashes before the asterisks, like this:

Markdown provides backslash escapes for the following characters:

Copyright © 2002–2022 The Daring Fireball Company LLC.

Basic Syntax

The Markdown elements outlined in the original design document.

Overview

Nearly all Markdown applications support the basic syntax outlined in the original Markdown design document. There are minor variations and discrepancies between Markdown processors — those are noted inline wherever possible.

Headings

To create a heading, add number signs ( # ) in front of a word or phrase. The number of number signs you use should correspond to the heading level. For example, to create a heading level three (

), use three number signs (e.g., ### My Header ).

| Markdown | HTML | Rendered Output | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Heading level 1 |

| Markdown | HTML | Rendered Output | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heading level 1 =============== |

| ✅ Do this | ❌ Don’t do this |

|---|---|

| # Here’s a Heading | #Here’s a Heading |

You should also put blank lines before and after a heading for compatibility.

| ✅ Do this | ❌ Don’t do this |

|---|---|

| Try to put a blank line before. . and after a heading. | Without blank lines, this might not look right. # Heading Don’t do this! |

Paragraphs

To create paragraphs, use a blank line to separate one or more lines of text.

| Markdown | HTML | Rendered Output | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I really like using Markdown. I think I’ll use it to format all of my documents from now on. |

| ✅ Do this | ❌ Don’t do this |

|---|---|

| Don’t put tabs or spaces in front of your paragraphs. |

Keep lines left-aligned like this.

Don’t add tabs or spaces in front of paragraphs.

Line Breaks

To create a line break or new line (

), end a line with two or more spaces, and then type return.

| Markdown | HTML | Rendered Output | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This is the first line. And this is the second line. |

| ✅ Do this | ❌ Don’t do this | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||