Translation ethics in the changing world

Translation ethics in the changing world

Ethics in Translation

As every other profession, translating relates to responsibility and making decisions. There is no doubt that the main responsibility of the translator is transmitting the correct information from the source text to the target text. Yet, how far may the translator go into deciding what will be translated and what will be omitted? According to Katharina Reiss, translation is always «subjectively conditioned» and the final form of the text is only «an interpretation». If translation is entirely subjective, are there any official rules of ethics for translators to follow?

National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI) suggests several general principles concerning translators and interpreters. These rules are derived from codes of ethics from different cultures all over the world:

These rules may seem universal, but in fact they are really broad. A more detailed set of ethic principles was proposed by Association des Traducteurs Littéraires de France (ATLF). It may be summarized as follows:

It needs to be said that sticking to these rules is not always enough. Every situation, every context, and every text is different. As Anthony Pym claims, the priority must be given to the intercultural character of the profession; and the translator should in the first place translate the cultures. In his conclusion, Pym presents two main questions which the translator asks himself constantly: «What will the reader say?» and «What will the client say?» An ultimate answer seems to be: «You decide!». Yet. decide wisely.

Bibliography:

Pym, A. (1992) Translation and Text Transfer. Berlin: Peter Lang Publications Incorporated

Reiss, K. (2000) Translation Criticism – The Potentials and Limitations. London: Routledge

American Translators Association Code of Ethics and Professional Practice (2010)

National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters Information Booklet (2016)

We Translate On Time is a translation company with the highest quality standards and the most competitive price on the market. Our translation company offers certified and non-certified translation services.

JALTranslation

Dr Joseph Lambert – BA, MA, PhD, FHEA

Translation Ethics: A Different Perspective

This post represents a long-overdue contribution as the question of ethics within translation is both a topic I find fascinating and one to which I have devoted considerable research. In fact, with it being the topic that was at the heart of my MA dissertation, I’d probably go as far as saying that it is my ‘specialist subject’ within translation studies – if such a thing exists.

I must also note that this post is merely an introduction to this vast area and I hope to write further posts on the topic in the future to expand upon the basic ideas set out here.

Although it has been widely acknowledged for some time that ethical considerations are an area of key importance for translation studies research and translation as a whole, relatively few scholars have sought to tackle the issue and even fewer bloggers or professionals writing upon translation have looked into this area.

One notable problem is that the very definition of ethics varies greatly between texts and people can find themselves addressing wildly differing concepts while still contending with the same umbrella subject. Furthermore, traditional concepts of ethics do not apply to translation in an adequate manner; sticking to ideas such as utilitarianism (used in the sense of the most happiness for the greatest number of people) or intellectualism (which dictates that the best action is the one that best fosters and promotes knowledge) can be viewed as a limitation of conceptions of ethics in this context.

Ultimately, ethics remains a challenging subject in any field and its breadth of applications ensures that no discussion of the subject will prove to be clear-cut. Indeed, as Sherry Simon puts it in her 1999 review of Lawrence Venuti’s The Scandals of Translation: ‘[w]hat more difficult notion is there in translation studies than that of the ethics of translation?’

However, whether or not that is the case, many of the posts I have read on the subject are particularly out of line with what I see as the key issues and I believe that some ground can be gained by looking into precisely what it is we are aiming for.

More specifically, the majority of posts I have read addressing the area are concerned with individual convictions and value judgements. One perfect example is this post from Jensen Localization entitled ‘Ethics in Translation’ that questions how differing views on topics such as religion or politics, or texts that may cause offence to the translator can lead to ethical problems. This is undoubtedly an important aspect of the profession and questioning the impact that these issues have on your output is extremely interesting, yet I don’t feel that this is a part of ethics proper.

Similarly, while an issue such as translators’ rights and drawing up a professional code of conduct for translators are both undoubtedly important, they place focus solely on a deontology, or professional ethics, while separating a personal ethics from the discussion.

For me, professional codes of conduct represent a different area of study while considerations such as whether or not a translator is willing to accept a text based on grounds such as religion or politics are individual decisions that lie within the distinct category of morality.

It is important that ethics contends with the question of how to translate; previously mentioned issues are not ethics of translating or translation, but of the translator.

As Anthony Pym puts it (a leading voice on the topic who himself continually refuses this distinction between deontology and ethics and seeks to address the profession and the act together in an attempt to develop one all-encompassing ethical code):

‘If any decision includes moral aspects, it follows that any act of translation, and any theoretical treatise on it, can be read from the point of view of ethics.’

In this statement he equates the act of translation as a whole with an ethics of translation and as a result implies that the ethics of translation is inextricably linked to a methodology of translation – the individual choices in the translation process, or that question of ‘How to translate?’

An ethics of translation lies in deciding upon the right course of action within the act itself, deciding what is the right or wrong treatment of the text we are translating and knowing how to implement those decisions. It implies an acute awareness of your own role in the translation process and a keen awareness of the impact of your decisions on the world around you.

One example which serves to demonstrate the distinction I have attempted to make is this provocative post that is currently causing some heated discussion among professional translators. Within the post, the author details and glorifies their method of ‘faking it’ in translation – getting work in the profession despite being wholly unqualified.

In terms of a professional or translator ethics, this is highly questionable as the client is not given an honest reflection of the translator’s capability to complete the work (the line ‘managed to convince some poor fool to pay me to translate Japanese for them’ really drives this home), while in terms of a translation ethics the translator is in no position to fully appreciate the significance of their choices or the subtle shades of meaning that are being erased, mangled or mistreated and is thus acting in an unethical manner.

Overall this is an extremely difficult area to address and I hope that this introduction has served to shed some light on what I believe is the true heart of a translation ethics.

What is the Role of Ethics in Translation Industry?

Interpreters and translators serve as the only gateway between two people who speak different languages. Therefore, the role of ethics in translation industry is certainly important.

Because they are usually hired to interpret in stressful or delicate situations, the set of rules and guidelines were created in order to secure and guarantee the high level of professionalism.

The theme of social responsibility emerged as a strong common concern across diverse contributions on interpreting, translation and other forms of cross-cultural communication.

Communication across languages and cultures clearly involves important questions for citizens and society at large, and the various participants in translated encounters – interpreter/translator, ‘client’ and ‘user’ – are confronted with broad issues of social responsibility. These issues often arise unexpectedly and with little or no prior training, preparation or opportunity to reflect on appropriate strategies to respond. It is ethics in translation industry that can prevent such problems in intercultural communication.

Social responsibility and the translation and interpreting professions

Interpreters and translators are faced with an abundance of ethical issues they must work through on a daily basis while professionally interpreting or translating in the field. There are a variety of scenarios in which professional interpreters and translators must maintain a high ethical standard in order to stay neutral and avoid intervening in a situation or perhaps muddling intended meanings. The ethical responsibilities taken on during language services are just as important to the success and completion of the translation or interpretation as the actual conversion of words. Ethics in translation industry is not something new to professionals working in this industry.

There are several common ethical standards which are accepted across all professions. While codes of conduct for translators and interpreters do exist in some countries, they mostly set out guidelines on issues related to professional competence. In other words, a professional focus on social responsibility may have an impact on individuals and society far beyond the narrow professional sphere.

Guidelines for the highly-qualified specialist

Multi-Languages Translators Code of Ethics defines what it means to be an outstanding translator. “Every translation shall be faithful and render exactly the idea and form of the original – this fidelity constitutes both a moral and legal obligation for the translator.” – International Federation of Translators

These guidelines are relevant for other professionals in the translation and interpretation business as well. Below is a summary of the main points from the code of ethics in translation industry.

Professional Practice

Translators should endeavor to provide service of the highest quality in their professional practice.

Accuracy

Interpreters and translators are hired for their ability to correctly understand what one client is saying and convey it accurately to the other. The translator must translate accurately. By accurate translation, we understand a translation that preserves the meaning, style, and register of the source document. Speaking about interpretation, it should be noticed that much of human communication is portrayed not through words, but facial expressions, the tone of voice, body language, etc. Interpreters should have clients speak to each other rather than to them, and make eye contact, to help them pick up on these nonverbal cues.

Confidentiality

An interpreter or translator is likely to be handling sensitive or otherwise confidential information. Even if it seems trivial, clients need to be sure they can trust you not to share it with other people. The translator must respect, under all circumstances, confidentiality and privacy of the information contained in all documentation provided by the client for the purpose of translation, unless otherwise required by law. All information submitted shall be confidential and may not be reproduced, disclosed or divulged.

Impartiality and Conflict of Interest

In order to maintain professionalism, the translator must remain impartial and declare any potential conflict of interest (including personal or ethical values and opinions) that may affect his/her performance while translating a document.

Limitation of practice

The translator must know his/her linguistic limitations and decline assignments that go beyond his/her skills and competence.

The translator must only accept assignments that he/she can complete and deliver in a timely manner (by the due date).

The translator must accept documents that he/she can translate. No work should be subcontracted to colleagues without prior written permission.

The translator should possess sound knowledge of the source language and be an expert in the target language.

The translator should accept translations only for fields or subject matters where he/she has knowledge and experience.

Sensitivity to Cultural Misunderstandings

There are some situations where conveying information is not enough. As an expert on the culture of both languages, a translator should be aware of any cultural differences that may interfere with effective communication.

Accountability

The translator is accountable for his/her work and must recognize and acknowledge translation mistakes and try to rectify them even when the translation has been completed, in order to avoid potential liability and risk issues.

Professional Development

Respect for all parties

The translator must show respect for all parties involved in the translation assignment, including respect for self, the agency and to its clients.

The translator must respect copyrights and intellectual property. Translated documents remain the client’s exclusive property.

A pursuit of Professional Development

Languages are constantly evolving, and new terminology comes to light in every field all the time. A translator needs to be aware of these changes to interpret and translate effectively.

Ethics in translation industry are important to uphold and it is vital to your reputation that you provide your clients, customers or patients with a value only professionals can provide.

Translation ethics in the changing world

Библиографическая ссылка на статью:

Станиславский А.Р. Этика и перевод: по ту сторону принципа эквивалентности и верности // Гуманитарные научные исследования. 2016. № 3 [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://human.snauka.ru/2016/03/14508 (дата обращения: 02.06.2022).

Традиционная этика перевода основана на понятии верности. Переводчик, как нам говорят, должен быть верным исходному тексту, автору исходного текста, намерениям текста или автора, или чему-то в этом общем направлении…

Энтони Пим, «Переводческая этика и электронные технологии»

Всякая профессиональная область или научная дисциплина в ходе своего естественного развития достигает стадии, на которой профессиональное или научное сообщество рефлексирует этические (моральные) аспекты своей деятельности, формулируя практические рекомендации и/или теоретические принципы по их воплощению. Это общее наблюдение относится к переводческой деятельности в целом и к переводоведению, в частности. В этой статье мы кратко рассмотрим основные работы по этике перевода, написанные авторами из стран бывшего СССР, и опишем круг теоретических проблем, обсуждаемых в контексте этики перевода зарубежными специалистами. В заключение мы назовем одно понятие, которое, по нашему мнению, является одним из ключевых признаков, отличающим многие новейшие подходы от традиционного взгляда на этику перевода.

В советский период вопросы этики переводческой деятельности практически не рассматривались.[i] Первые обстоятельные публикации, в которых авторы затрагивают этические вопросы в работе переводчиков – преимущественно устных, – появляются только в конце 1990-х годов. Так, представитель старшего поколения российских переводоведов Р.К. Миньяр-Белоручев посвящает этикету работы устного переводчика целую главу в своем пособии 1999 года [1, с. 86-93].

Известный украинский специалист Г.Э. Мирам в книге, опубликованной также в 1999 году, уделяя достаточно много внимания вопросам этикета в работе устного переводчика, формулирует и задачу этического характера, актуальную, по его мнению, для всего отечественного переводческого сообщества: добиться «четкого определения, статуса переводческой профессии». Ссылаясь на опыт западных коллег, автор видит решение этой задачи в наличии у переводчика «рабочего контракта, в котором должны быть четко оговорены функции переводчика и плата за их выполнение» и в создании «профессионального союза (объединения) переводчиков, защищающего права переводчика». [2, с. 145-149]

В том же 1999 году А.П. Чужакин и П.Р. Палажченко формулируют уже десять правил переводческой этики (устного) переводчика:

Правило № 1 (основное правило профессиональной этики перевода) – не разглашать информацию, обладателем которой становишься.

Правило № 2 – желательно установить доверительные отношения с теми, на кого работаешь.

Правило № 3 – необходимо соблюдать выдержку и хладнокровие даже в экстремальных обстоятельствах, быть всегда корректным, вежливым, аккуратно и к месту одетым, подтянутым и четким пунктуальным и предупредительным (как говорится comme il fault, т.е. «комильфо»).

Правило № 4 – по возможности, не добавлять от себя (не выходить за рамки сказанного), воздерживаться от комментариев и выражения своей точки зрения, не отпускать без нужды часть информации.

Правило № 5 – в случае необходимости пояснять особенности национального характера, менталитета, традиций и культуры, знакомых переводчику и неведомых вашему партнеру, с тем чтобы повысить КПД общения и достичь более полного взаимопонимания.

Правило № 6 – следует оказывать конкретную помощь, когда она требуется тем, кто недостаточно ориентируется в ситуации, в особенности за рубежом, даже вне рабочего времени и без дополнительной оплаты.

Правило № 7 – постоянно повышать квалификацию, профессиональное мастерство, расширять и углублять эрудицию в различных областях знания, специализируясь, по возможности, на одном направлении (право, финансы, экология и пр.).

Правило № 8 – щедро делиться знаниями и опытом с молодыми и начинающими переводчиками.

Правило № 9 – соблюдать корпоративную солидарность и профессиональную этику, повышать престиж профессии, не идти на демпинговую оплату своего труда.

Правило № 10 (шутливое) – случайно нарушив одно из правил, не попадаться! [3, с. 13-14]

Наиболее развернутая характеристика этической проблематики в профессиональной деятельности переводчика на постсоветском пространстве представлена в многократно переиздававшейся книге И.С. Алексеевой «Введение в переводоведение» [4]. Отдавая должное работам своих коллег ([1], [2], [3] и др.), она справедливо утверждает, что «связного представления о профессиональной этике переводчика новейшие публикации нам все же не дают» [4, с. 28]. Моральные принципы переводчика Алексеева формулирует в виде шести «основных правил переводческой этики»:

Эти шесть постулатов она далее дополняет еще пятью:

В контексте этики перевода Алексеева также рассматривает нормы профессионального поведения переводчика («правила ситуативного поведения»); профессиональную пригодность и профессиональные требования; знакомство с техническим обеспечением перевода, а также правовой и общественный статус переводчика (включающий объединение переводчиков в профессиональные союзы и ассоциации, в т.ч. международные). [4, с. 34-42]

Как мы видим, процитированные правила переводческой этики/этикета от Миньяр-Белоручева до Алексеевой, по сути, представляют собой рекомендации начинающим переводчикам на основе практического опыта, накопленного старшими коллегами, переводчиками-профессионалами. В этих «сводах» правил обращает на себя внимание отсутствие ссылок или указаний на какие-либо теоретические концепции в области перевода, имеющие отношение к этике. Это вызывает, по крайней мере, два закономерных вопроса: существуют ли такие концепции в природе, и, если да, то какой новый свет они могут пролить на этические аспекты перевода и как области профессиональной деятельности, и как научной дисциплины.

Из текста И.С. Алексеевой создается впечатление, что никаких серьезных теоретических работ в области этики перевода до 2012 г. (год выхода 6-го издания «Введения в переводоведение») не было:

Типично лаконичное упоминание о ее необходимости [профессиональной этики – А.С.], как это делается в наиболее полном справочно-энциклопедическом пособии по проблемам перевода «Handbuch Translation» издания 1999 г., [ii] где обозначены лишь цели существования профессиональной этики: «осознание будущим переводчиком меры его профессиональной ответственности и необходимости хранить тайну информации». [4, с. 28]

Однако даже беглого анализа только англоязычных справочно-энциклопедических пособий показывает, что этическая проблематика перевода – предмет серьезного теоретического анализа. Вот только три полноценных статьи из энциклопедических справочников издательства «Рутледж» последних лет:

Можно говорить о консенсусе между зарубежными исследователями по вопросу, почему этика перевода, интересующая переводческое сообщество с давних времен, до относительно недавнего времени не удостаивалась серьезного теоретического осмысления.

Этичная практика всегда была важным вопросом для устных и письменных переводчиков, хотя исторически центром внимания был вопрос о верности устного или письменной текста. [5, с. 100]

Она [традиционная переводческая практика – А.С.] обычно занималась вопросами, касающимися текста, в первую очередь, отношением между переводом и оригиналом или имела своего рода прикладной характер, фокусируясь на обучении и практической критике, чаще всего в сфере лингвистики или художественной литературы. [6, с. 93-94]

На протяжении всей истории переводческий дискурс был преимущественно озабочен вопросами верности и эквивалентности, т.е. извечным вопросом о том, что переводчики должны сделать для того, чтобы достичь наиболее подходящего воспроизведения иностранного или родного в другом языке и контексте. Поскольку «этика» в целом относится к системам ценностей и моральных принципов, которыми должны руководствоваться наши представления о правильном и неправильном и тем самым дисциплинировать нас, справедливо утверждать, что история переводоведения – это, по большей части, и история этики перевода. … На протяжении большей части истории дискурса перевода на Западе этика как таковая не рассматривалась, поскольку считалось само собой разумеющимся, что «правильным» поведением переводчика является верность тексту и автору и что «хорошим переводом» является перевод, наиболее идентичный оригиналу. [7, с. 548-549]

Представляется, что практические рекомендации постсоветских авторов в целом укладываются в описанную зарубежными исследователями традиционную парадигму, ставящей во главу угла эквивалентность и верность перевода (оригиналу/автору/требованиям клиента). Это предположение можно проиллюстрировать фрагментами из книги И.С. Алексеевой:

Основным инструментом научной критики перевода служит понятие эквивалентности, которое применяется к конкретным результатам перевода. [4, c. 50]

Какие же изменения, по мнению зарубежных исследователей, произошли в практике перевода (и когда?), которые поставили под вопрос этот традиционный взгляд на то, что «хорошо» и «плохо» в переводе?

Мойра Ингиллери ссылается на работу Энтони Пима с характерным названием «Возвращение к этике» [8], в которой последний связывает возрождение интереса к этике «расширением параметров перевода», которые начинают учитывать, в частности, особую роль, или «представительство» (agency) переводчика. Год выхода работы Пима – 2001. [5, c. 100]

Тео Херманс для характеристики изменений в переводоведении в качестве иллюстрации кратко описывает новейшую историю исследований в области устного перевода:

Ранние исследования были почти исключительно связаны с когнитивными аспектами синхронного перевода на конференциях (conference interpreting), исследованием таких вещей, как способность переводчика обрабатывать информацию и емкость памяти (…). Однако исследование поведения иракского переводчика в накаленной атмосфере интервью Саддама Хусейна британским тележурналистом накануне войны в Персидском заливе 1991 года выявило совершенно иные ограничения в его работе; они были непосредственно связаны с вопросами власти и контроля, поскольку Саддам неоднократно поправлял сильно нервничающего переводчика [9]. В течение последнего десятилетия или около того исследования в области устного перевода претерпели существенные изменения вследствие растущей важности «сопровождающего» или «общественного» перевода (community interpreting), который в отличие от синхронного перевода на конференциях обычно происходит в неформальной обстановке, иногда в атмосфере подозрительности, и часто оказывается эмоционально окрашенным. [6, с. 94]

Бен Ван Вайк считает, что основательный пересмотр традиционного понимания этики перевода произошел примерно в последние двадцать лет [7, c. 548], и связывает его с работами французского философа Жака Дерриды. Деррида полагал, что «поскольку оригинал является нестабильным объектом, постольку он может истолковываться по-разному, а так как языки существенно отличаются друг от друга, перевод никогда не может быть «переносом» смысла и всегда влечет за собой его «преобразование» (…)». Как следствие:

…переводчики уже не могут больше рассматриваться в качестве беспристрастных посредников, а являются «представителями» (agents), которые играют основную роль в создании смысла, являющегося сутью их переводов. Короче говоря, переводчики никогда не смогут выполнить перевод, не предполагающий различия, перевода, обеспечивающего однозначный смысл оригинала, или перевода, который как таковой невосприимчив к множественности толкований.

Следовательно, переводчики должны брать на себя ответственность за свои решения и больше не могут делать вид, будто они невидимы, прикрываясь тем, что они просто повторяют то, что увидели в оригинале, или то, что автор мог подразумевать. [7, с. 551]

Кратко охарактеризуем только самые часто упоминаемые направления, в которых движутся новейшие исследования зарубежных специалистов в области этики перевода.

Функционализм и скопос-теория

В числе теоретических концепций, в рамках которых происходит сдвиг в изучении этических аспектов переводческой деятельности, одной из первых называют функционалистские подходы к переводу и скопос-теорию, разработанные Гансом Фермеером и Катариной Райсс, а позднее дополненные Кристианой Норд «принципом лояльности». Так, Херманс отмечает, что в противоположность традиционной критике переводов, которая «редко шла дальше вынесения суждения о качестве конкретного варианта [перевода], функционалистские исследования (…) искали ответы на такие вопросы, как: кто заказал перевод, или какая цель ставится перед переведенным текстом в его новом окружении» [6, c. 94].

Еще раньше Херманса на роль скопос-теории (в интерпретации Кристианы Норд) в переоценке этики перевода обратила внимание Кайса Коскинен в своей диссертации «За пределы амбивалентности: постмодернизм и этика перевода» (2000 г.):

В рамках этой концепции успех или качество перевода измеряется не путем сравнения его с оригиналом, а оценивается тем, насколько хорошо перевод удовлетворяет свой «скопос» (цель) и отвечает потребностям клиента и целевой аудитории. [10, с. 20]

Об этической направленности «принципа лояльности» сама Кристиана Норд прямо говорит в одной из своих более поздних публикаций:

Принцип лояльности был введен в скопос-теорию в 1989 году (…) для учета культурной специфики переводческих концепций перевода, назначения этических ограничений [выделено нами – А.С.]в иначе неограниченный круг возможных «скопосов» (целей) перевода одного конкретного исходного текста. Было высказано предположение, что переводчики в их роли посредников между двумя культурами несут особую ответственность как в отношении своих партнеров, то есть автора исходного текста, клиента или заказчика перевода, целевых получателей текста, так и самих себя, именно в тех случаях, когда имеются разногласия относительно того, каким должен быть «хороший» перевод. [11, с. 2-3]

Норд также высказывает надежду, что ее «принцип лояльности» сможет заменить традиционный «принцип верности», который «обычно указывает на лингвистическое или стилистическое подобие между исходным и целевым текстами, независимо от имеющихся коммуникативных намерений и/или ожиданий». Лояльность у Норд, таким образом, становится центральным понятием в новой этической парадигме перевода:

Поэтому, вводя принцип лояльности в функционалистскую модель, я хотела бы также надеяться заложить основы доверительных отношений между партнерами в их переводческом взаимодействии. [11, с. 3]

Дескриптивизм

Наряду с функционализмом еще одной концепцией, с которой ассоциируют изменения в этической «картине» перевода, называют дескриптивизм, связанный с именами таких исследователей как Тео Херманс, Сильвия Ламберт, Андре Лефевр и Гидеон Тури. По словам Херманса, дескриптивисты задавались теми же вопросами, что и функционалисты, но их больше интересовали «историческая поэтика и роль (преимущественно) литературного перевода в конкретные исторические периоды»:

В рамках дескриптивистской парадигмы Андре Лефевр, в частности, пошел дальше и начал исследовать, каким образом переводы встроены в социальные, идеологические, а также культурные контексты. Его ключевое слово было «патронат», которое он понимал в широком смысле как любое лицо или учреждение, способное осуществлять значительный контроль над работой переводчика. [6, с. 94]

Нормы

Херманс пишет, что из опыта практикующих переводчиков, постоянно принимающих решения относительно как собственно перевода, так и организации процесса перевода (напр., отношения с заказчиками) родилась еще одна концепция – понятие о переводческих нормах. Эта концепция, будучи социально-психологической по своей природе, с одной стороны, учитывает ценностные факторы сообщества, в котором работает переводчик, а с другой, учитывает общественные и индивидуальные ожидания о характере поведения и выборе решений переводчика в той или иной ситуации. [6, с. 95]

Согласно Хермансу, Гидеон Тури в [12] рассматривал нормы «преимущественно в качестве ограничений поведения переводчика», которые, по совокупности принятых переводчиком под их влиянием решений, «определяют форму окончательного текста». Впоследствии эта концепция была оптимизирована путем учета взаимодействия между переводчиком и аудиторией. Директивный характер норм «диктует каждому человеку, какие утверждения являются социально приемлемыми». [6, с. 96]

Херманс также пишет, что Эндрю Честерман в [13] и [14] «относил нормы к профессиональной этике, которая, – утверждал он, – требует приверженности адекватному выражению, создания точного подобия между оригиналом и переводом, обеспечения доверия между сторонами, участвующими в процессе, и минимизации недоразумений»:

Опираясь на кодексы этичного поведения профессиональных организаций, Честерман даже предложил, чтобы устные и письменные переводчики во всем мире давали «клятву Иеронима», аналогичную «клятве Гиппократа», которую дают медики [15]. [6, с. 96]

Нарратология

В числе недавних теоретических концепций, оказавших влияние на современное представление об этике перевода, Мойра Ингиллери называет нарратологический подход, предложенный Моной Бейкер в [16]. Эта концепция опирается на работы Уолтера Фишера в области коммуникативных исследований, утверждавшего, что «люди решают, считается ли что-либо этичной практикой – иными словами, было ли что-либо сделано из «добрых побуждений», – опираясь на нарративы («повествования»), которые они принимают о мире, в котором они живут, а не на абстрактную рациональность, укорененную в трансцендентных идеалах»:

Нарратологический подход может предложить инструмент для более углубленного прочтения нарративов, создаваемых профессиональными ассоциациями письменных и устных переводчиков с целью оказания помощи переводчикам в принятии более информированных решений как относительно мотивов – почему они придерживаются или отвергают определенные ценности, – так и относительно возможных социально-политических последствий таких действий. [5, с. 103]

«Межкультурное пространство»

Еще один подход, претендующий занять место новой этики перевода, был предложен Энтони Пимом (см., напр., [18]). Кайса Коскинен утверждает, что основная идея этого подхода состоит в том, что «переводчики находятся в особом межкультурном пространстве, на перекрестке культур». Пим, на основании своих теоретических размышлений, формулирует пять этических принципов [18, с. 136-137], [10, с. 81]:

«Этика различий» и «невидимость переводчика»

Идеи, которые, пожалуй, чаще других приводятся для иллюстрации глубины концептуального сдвига в осмыслении этических аспектов перевода получили названия «этика различий» (ethics of difference) и «невидимость переводчика» (translator’s invisibility). Ван Вайк так характеризует представителей этого направления:

Фактически, многие современные теоретики перевода, которые считают себе сторонниками того, что называется «этика различий», утверждают, что этическая ответственность переводчиков должна состоять в том, чтобы ставить под вопрос и расшатывать конвенции, которые обычно затемняют тот факт, что в языке могут отражаться и другие реальности; конвенции, которые представляются нейтральными и естественными, но на самом деле отражают определенные интересы и предпочтения (…). [7, с. 552]

К одним из наиболее влиятельных теоретиков этого направления Ван Вайк относит Лоуренса Венути, «значительная часть работы которого – стремление расшатать традиционную этику, которая вращается вокруг понятия невидимости переводчика, в частности, в контексте перевода на доминирующий язык, английский»:

Для Венути то, что мы обычно считаем невидимостью, на самом деле, является соответствием определенным ожиданиям и интересам, исходящим от доминирующих сил, которые требуют «гладких» переводов, выглядящих так, как будто они вовсе и не переводы [17]. [7, с. 552]

Херманс пишет, что для противодействия негативным последствиям гладкости «Венути предлагает и практикует в своих собственных переводах с итальянского языка форму резистентного или «миноритизующего» (“minoritizing”) перевода, первоначально называвшегося им «форенизирующим» (…). … Конечная цель переводов Вентути – бросить вызов лингвистической и идеологической гегемонии и внести вклад в смену мировоззрения». Созвучны методологическим интенциям Венути и работы, обобщающие переводческий опыт в русле феминистских, пост-колониальных и пост-структуралистских теорий (см., напр., [19], [20], [21], [22]). [6, с. 99]

Попытку преодолеть грубое противостояние национального и глобального, провинциального и космополитического предпринял Майкл Кронин в [23] и [24]. Обосновывая идею «микро-космополитизма», он, согласно Хермансу, «стремится настроить зрение на множество мельчайших сложностей местного, не забывая при этом о более обширных контекстах»:

Кронин выступает против представления о переводе как средстве стимулирования разнообразия. Перевод, как он видит его, согласовывает смысл и тем самым создает промежуточную зону посредничества, которая является социально необходимой в густонаселенных поликультурных центрах. [6, с. 104]

Подводя итоги нашему небольшому экскурсу в круг этической проблематики, интересующей зарубежных теоретиков перевода, представляется, что одним из ключевых признаков, по которому большинства описанных концепций отличаются от тех, которые принято считать традиционными (ориентированными на приоритет эквивалентности и верности), является то, что Тео Херманс обозначает термином «вмешательства» (interventions) [6, с. 100]. Учет будь то функциональных, нарратологических, межкультурных или «миноритизующих» факторов требует от переводчика демонстрировать свое «представительство» (agency), или, иными словами, вмешиваться (intervene) в процесс «традиционного» перевода. Характер и глубина этого вмешательства зависит от конкретных идеологических или методологических установок переводчика, но именно вмешательство (intervention), по нашему мнению, является типологическим маркером новых этических концепций.

Вот несколько отрывков из текстов авторов этических концепций, о которых мы говорили в статье, свидетельствующие в пользу нашего предположения об интегрированности «принципа вмешательства» в их теоретические построения.

Кристиана Норд в ранее процитированной статье, характеризуя предложенный ей «принцип лояльности», говорит о праве переводчика на любые обоснованные изменения в текст оригинала и приемлемости такой процедуры (при соблюдении определенных условий) для остальных участников процесса перевода:

Если авторы будут уверены, что переводчики уважают их коммуникативные интересы или намерения, они могут согласиться и на любые изменения или адаптации, необходимые для того, чтобы перевод «заработал» в целевой культуре. А если клиенты или получатели будут уверены, что переводчик учтет и их коммуникативные потребности, они могут даже принять перевод, который будет отличаться от того, что они ожидали.[iii] Эта уверенность только укрепит социальный престиж переводчика как ответственного и надежного партнера. [11, с. 3]

Лоуренс Венути в своем программном труде «Невидимость переводчика» прямо говорит о неизбежности вмешательства в оригинал при переводе:

Мона Бейкер в 2008 году дала большое интервью Эндрю Честерману [26]. Отвечая на вопрос Честермана в связи с выходом сборника статей «Перевод как вмешательство» [27], как она относится к пониманию перевода как посредничества (mediation), Бейкер указала, в частности, на то, что вмешательство – это действие, «к которому любой ответственный переводчик захочет хот бы однажды прибегнуть в своей карьере». «Вмешательство, – продолжила она, – может также означать продолжение посредничества и, вы, оставаясь «верным» насколько возможно, когда «говорите от имени другого», в то же самое время отстраняйтесь от этих идей и даже ставьте их под вопрос» [26, с. 16].

Далее в своем интервью Бейкер делает еще более категоричное заявление:

Не опосредованного, свободного от вмешательства перевода просто не бывает, даже если переводчик убежден, что должен быть абсолютно нейтральным. А с учетом того, что устные и письменные переводчики живые люди, с совестью и чувством того, что этично или неэтично, неизбежно возникают ситуации, в которых они не смогут избежать вмешательства и в более прямом смысле этого слова. [26, с. 19]

Энтони Пим в одной из относительно недавних публикаций говорит даже не о «вмешательстве» переводчика, а об его активном «улучшении оригинала»:

Перевести – это попытаться улучшить оригинал

Отказ от естественного нейтралитета позволяет решить несколько острых вопросов, обычно избегаемых этикой анонимности. Самая важная из этих проблем – право или обязанность переводчика улучшать оригиналы (…). Поскольку переводчики не могут не занимать ту или иную позицию – ибо даже нейтральные позиции должны быть созданы, – их этика должна порвать с пассивной безличностью, заставив их активно оценивать тексты, над которыми они работают, брать на себя основной груз ответственности за тексты, которые они создают. [28, с. 170]

Как мы надеялись показать в статье, постсоветские специалисты не углублялись в обсуждение теоретических аспектов этики перевода, ограничиваясь, главным образом, выдачей практических рекомендаций по соблюдению набора правил этической направленности с весомой долей правил этикета переводчика. В трудах специалистов, работающих за пределами бывшего СССР, с другой стороны, можно найти большой спектр теоретических концепций, связанных с этикой перевода, которые выходят за рамки господствующей парадигмы, согласно которой этичным считается перевод, обеспечивающий его эквивалентность и верность. Общим «знаменателем» многих новейших концепций, по нашему мнению, является принцип допустимости вмешательства в оригинал с целью соблюдения этических норм, предполагаемых соответствующей концепцией.

[i] Некоторый интерес к этической проблематике со стороны советской переводческой общественности можно отметить, в частности, на примере публикации в выпуске авторитетного сборника «Мастерство перевода» за 1964 год [29] «Хартии переводчика» Международной федерации переводчиков. Среди декларируемых целей указанного документа указывалось изложение «некоторых общих принципов, неразрывно связанных с профессией переводчика» дабы «подчеркнуть социальную функцию перевода; уточнить права и обязанности переводчика; заложить основы морального кодекса переводчика»; улучшить экономические условия и социальную атмосферу, в которой протекает деятельность переводчика; рекомендовать переводчикам и их профессиональным организациям известные линии поведения» [29, с. 496-500].

[ii] Любопытно, что на этот же неновый иностранный источник ссылаются авторы еще одной недавней публикации на тему профессиональной этики переводчика [30, с. 15].

[iii] Автор настоящей статьи может подтвердить справедливость этих предположений на личном опыте. В процессе перевода на русский язык американских пособий по письменной стилистике и композиции оригинальные тексты подверглись сокращению и адаптации с целью сохранения их коммуникативных задач для новой аудитории (о чем сказано в предисловиях переводчика к каждому переводу [31, с. 10-11], [32, с. 16-17]). Со стороны всех заинтересованных лиц – авторов, издательств (оригинальных текстов и переводов) – было встречено полное понимание и содействие.

Связь с автором (комментарии/рецензии к статье)

Оставить комментарий

Вы должны авторизоваться, чтобы оставить комментарий.

© 2022. Электронный научно-практический журнал «Гуманитарные научные исследования».

The Issue With The Ethics of Translation And Interpretation

By Clara Lorda

While codes of conduct for translators and interpreters do exist in some countries, they mostly set out guidelines on issues related to professional competence. For instance, the American Translators Association (ATA) has a formal code of ethics that all members must adopt and follow. But what about a translators’ or an interpreters’ personal code of ethics?

Ethics of Translation and Interpretation: Interpreter Ethics

While writing about this topic, a particular story came to mind: An interpreter I know personally was interpreting for a real estate agency during the purchase of a property. On one occasion, during a meeting between the brokers and buyers, the two real estate brokers for which the interpreter was working suddenly started to make fun of the buyers. An interpreter is obligated by their profession to interpret everything that is being said, so it is easy to guess how conflicted the interpreter must have felt at this point. What was she supposed to do? She decided to let the brokers know that she would interpret every word from that point on, and so they stopped mocking the buyers.

Interpreters are in a slightly different situation than translators in terms of dealing with ethical situations, due to they very fact that their personal morals will (or potentially will not) coincide with the expected professional morals as set out by various institutions – examples include the Ethics and Standards for Interpreting in medical situations, as presented by the National Council on Interpreting in Health Care (NCIHC), or the Code of Ethics for Legal Interpreters, as presented by the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida. Although not all institutions will outline a particular “code of ethics”, most expect interpreters to behave in a similarly professional and impartial way. It is in the best interests of anyone looking to hire an interpreter to check that the agency contracting them vets all linguists in its network to ensure they work according to the these expectations.

Ethics of Translation and Interpretation: Translation Ethics

Translators also experience ethical dilemmas that are more related to their personal views. For instance, would a translator translate the instructions for an automatic rifle if he knows the target readers are teenagers in Sudan? Would he translate a pamphlet containing neo-Nazi ideology? What about if he is pro-choice, would he interpret for a pro-life group? To translate or not to translate, that is the question. There are several opinions regarding this issue depending on whom you ask. Some professionals think that it is essential to separate your personal convictions from your professional life, but to what extent is this possible? One of the requirements to achieve quality translation services is to be faithful and accurate to the source text and this entails there is no place for subjectivity.

This begs the question whether a translator is able to provide a quality product if it involves betraying himself or herself? As I mentioned before, it probably will depend on the individual translator. It will also depend to some extent on the individual’s personal circumstances. For example, a junior translator is less likely to be picky about what he is asked to translate, especially if this is his only source of income. To some degree this situation resembles the concept of a fair juror at a trial. Like jurors, translators and interpreters at times must make difficult ethical choices. In most cases, these choices positively affect their professionalism as they ensure dedication to a quality product. Hiring a translator through an agency will likely guarantee some security when it comes to ensuring your project is completed – however, if there are any concerns this should be talked through with a project manager before the launch of the project.

The Ethics of Translation

Just as professionals such as doctors and lawyers occasionally grapple with ethics, translators and interpreters will likely face a range of ethical dilemmas in the practice of their profession. Certain countries have established codes of conduct that set out guidelines for issues such as quality standards, impartiality, and confidentiality; however, the truly difficult decisions arise when linguists are asked to translate a text that clashes with their personal ethical standards.

Consider these situations:

The role of a translator is to objectively render the message provided in the source language into the target language. Ideally, linguists detach themselves from the topic in order to achieve the highest degree of objectivity when reproducing the message. A translator should be able to produce a sound translation even when his or her views come in conflict with those expressed in the text; however, if the source text tackles an issue that the translator feels so strongly about that it precludes his or her ability to remain detached and professional, then the translator should turn down the project.

In addition, it’s important to remember that many subjects are distasteful or unpleasant (e.g. reports of human rights violations), yet information concerning these topics is often needed to help combat horrific practices, investigate crimes, etc. Translators must evaluate not only the topic of the translation but also its end use.

Virtually all professional translators draw the line at translating texts that describe illegal activity, but when the topic of the translation falls into an ethical gray area, the decision to accept or reject the project on moral grounds ultimately rests with the translator. With that said, individuals who rely on translation to put food on the table may be slightly more open-minded than those who can afford to turn down unsavory projects thanks to other sources of income.

All freelancers have the right to choose which projects they take on. If they do turn down a translation, they don’t necessarily owe the client an explanation; nonetheless, it can be helpful to let the client know the reason for the rejection. In many cases, the client/agency will be understanding and supportive; however, translators should be aware that by turning down a project, they run the risk of losing the client.

If objectionable themes are likely to arise with a particular client, translators should consider adding a clause to their contract with that client, outlining the subjects the translator refuses to handle for ethical reasons. Another idea is to draw up a statement of principles, which summarizes the types of texts the translator will not accept on moral grounds. This statement may be sent to translation agencies or direct clients looking to engage the translator’s services so that his or her limits are clear from the very beginning.

ProZ.com Translation Article Knowledgebase

| Search Articles |

| About the Articles Knowledgebase |

ProZ.com has created this section with the goals of: Translator ethics and professionalism |

By InfoMarex | Published 04/30/2010 | Translator Education | Recommendation:      |

| Contact the author |

| Quicklink: http://www.proz.com/doc/2969 |

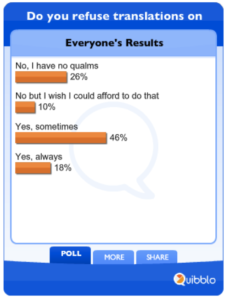

Translator ethics and professionalism in Internet interactions (Published in two instalments in Caduceus, the quarterly publication of the Medical Division of the American Translators’ Association (ATA), Summer and Fall 2006) Michael J McCann MA MITIA Tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis. Though specific actions change with the passing of every hour in the flow of our individual timeline, there are some matters which do not change. These are the principles under which we conduct ourselves. In more ancient times, it was held by common wisdom that times change and we change with them in the sense that we adapt or are forcibly adapted to change over time. Whether we adapt perceptibly or not, voluntarily or not, there is within our mental framework an overarching umbrella of thought which influences that adaption which we call conscience. It is a ‘studied observation of things together’ etymologically from the Latin cum scientia, and that knowledgeable observation is guided by a set of internal principles which, depending on your background and education, we call ethics or morals. Our ethics (Gk. customs) are not something which we have invented but rather come down through generations. They are not handed down in word-perfect format, though some principles may so be passed on as a Decalogue of religious and social commandments learned by rote whose internal values are perceived, appreciated and accepted. Similarly to shared words of a language for communication, our ethics are principles bout actions and works shared with others who interact with us. Many ethical principles we accept internally and immediately, recognising them as being relevant to our conduct. Our Roman forbears accepted these principles calling them morals (Lat. mos, mores) which influenced good conduct. No nation or civilisation has been able to develop without ethics or a moral value system. It is particularly significant, from a historical perspective and time span, that those transient civilisations which did not have a strong ethical fibre in their conduct, particularly of public affairs, declined very quickly. We merely have to look at those nations which sprang up and disappeared in the last century alone, within a short number of years, where so-called ‘cultures’ quite literally halved populations such as the Pol Pot régime in Cambodia or crippled a nation economically as the Third Reich did to Germany. While populations may be forced to endure such civilisations, at the earliest opportunity, populations will move, not just fleeing a persecution, towards a better and fairer moral value system. If a significant number of private moral or ethical values were not transposed into public affairs, then that particular nation would soon slip into decline. Those nations which have had important and meritorious principles of ethical conduct have always attracted attention and support. For nations, please now read ‘groups’, ‘associations’, ‘communities’, etc. For historical times, now read the ‘present day’. In modern times, professional groupings take unto themselves a code of conduct which they call ‘ethics’. It is not that they have invented the principles of the code, but rather they have taken many, but at times not all, of the principles and applied them to their profession. Hence, we talk, for example, of ‘medical ethics’ or the ‘ethics’ of the nursing, legal or accounting professions. The medical profession, in most countries of the world, follows the principal tenets of the ancient physicians, Hippocrates and Galen, in the observance of various medical principles, of which of ‘first, do no harm’ to the patient is but one. It does not mean that harm will not come to the patient with the treatment, but that, in theory and in adherence to respected practice, the medical professional will attempt not to permanently hurt the individual. The Internet is with us for less than a quarter of a century, if one takes the first basic TCP/IP network of 1983 as its starting point. It is now impossible to imagine the modern world without the Internet. It provides communication at many levels from private one-to-one emails, public mailing lists, confidential and secret transmission of sensitive coded data of all sorts, down to injurious and annoying spam. In the centre of this apparent maelstrom of communication transmission, the translator is becoming increasingly important. Where importance occurs, values follows and principles trail. Nowadays, the translator uses that professionalism to ‘type over’ an electronic text, or using optical character recognition (OCR) software will extract a text for processing with ease from a document. The translator is using another set of skills, but the underlying ethical principles must still apply. The Internet interaction between client and translator is immediate to everyone’s advantage. An unavailable translator can recommend other colleagues with a couple of keystrokes. The ‘letter’ stating unavailability is back with the client in minutes as an ‘email’. What is amazing compared to pre-Internet eras is the speed of the various transactions from setting up the translation to its final delivery and payment. While on the one hand the Internet may appear anonymous in that clients are not seen face to face, or the translators applying their skills to effect the translation do not meet the client, if we stand back and look at the situation it is no more anonymous that buying a tin of beans from a producer whom we have never met. The bottom professional and ethical line must be in the terms of a hypothetical ‘Sale of Goods and Services Act’ that the translation must serve the purpose for which it is meant. This present article is not meant to be prophetic, but it is not beyond the bounds of imagination that standard emails from clients in some years time, will have a clickable link where the client in a movie clip will explain, verbally and visually, the terms and conditions of the required translation. One could say that, with an international tool like the Internet, English as a language will dominate as it does in music and in international business. In one sense, this is partially correct as English as a language, at the last count, accounted for 55% of Internet transmission, with some two hundred principal other languages vying for small percentages of the 45% balance. What one does see as a professional translator is the continuous flow of translation of subject matters into English, far, far in excess of the flow towards any other language. This in itself is not a cause for concern, because the translator is not there to influence the marketplace, but what is of concern, at the quality control level, is the lack of standards applied to translation into proper English. Not just the text, but the language itself, must be treated as that Hippocratic patient to whom no harm must be done, causing mongrel versions of the language to be created by carelessness. The immediacy of work obtained and transmitted via the Internet also gives rise to a series of concerns. Gone are the days when an enterprise would request the translation of a text and be willing to wait a week to see if any translator applied for the job. Nowadays, through the Internet, an enterprise will have a number of translators electronically queuing up before close of the day’s business, ready, willing and able to translate the text in question. In this context, we are talking of a text without problem as to its content and we are talking of translators without problem as to their professional competence. The quaint picture of an erudite St. Jerome patiently labouring over the translation of a biblical text from Greek to Latin, penning each word with an old fashioned quill, without a shelf of hardcopy dictionaries to hand for reference, without the facility of a Google search for a comforting confirmation, is well removed from modern reality. The modern translator has tools undreamt-of in the past to hand, and strangely enough, with these tools come new ethical and professional responsibilities. Using the Internet, the ‘new’ translator is remarkably different to the translator of yore. Generally now, he or she is faceless, known to the client or the agency only as the voice at the end of a phone-line or as the person whose CV/résumé has been provided with copies of degrees, diplomas and references. The ‘new’ Internet translator whether working individually or in a collective situation bears the same burden of professional ethics as the pre- Internet translator. The over-riding principles stay the same; the relative conditions change with every text. However, the ‘new’ translator whose conscience is provoked or aroused by moral principles as to a translation situation has all the advantages of the advances of the Internet in seeking help quickly from other professionals or from an association body. Each translator, in his or her own daily endeavours will normally apply without thinking ethical principles. Here, one is making the huge assumption that the translator is of sound and healthy mind. What the Internet—and here one is talking of the more serious side of its communications—has brought to our lives is essentially immediacy and information. It is up to the translator to know how to use both of these in a responsible manner, guided not just by personal relativistic convenience, but by a principled focus on what is right in itself, not right by circumstance. There is also the question of ethical non-translation which trustfully will not rear its head too frequently in a professional life. Non-translation is an underdeveloped concept in the whole area of translation. It refers to four areas: the translator, the client, the text, and the conditions under which the first three come about. The translator is under no professional or ethical obligation to translate everything that comes across his/her desk. This is a very difficult statement to make but it stands to reason, even for translators who are full-time employed by a client/employer. Simple examples prove the point. The translator is competent in translating from Spanish. A client may request a translation from Portuguese – are they not very similar languages? [a true life example]. The translator must refuse out of professional competence. The interaction of all three aspects above – translator, client and text – give rise to the fourth aspect, namely the conditions. Ethical considerations also attach to the conditions. The translator may well decline the work because it is known in the business that the client does not pay on time. This may be of small importance to the translator, but can be of huge importance to an agency where cash flow is king, and the agency’s own translators have to be paid on time. There may also be the ethical aspect of a rate which is cut-throat, or of a deadline which is impossible to meet under normal professional conditions, or even the simple ethical nature of a translator’s promise to be home for Thanksgiving which would have to be set aside to meet the client’s demands [a true life example]. There is a debate also raging as to areas of competence. Interpreters know this and will seek out terminology before going into conference s on specific topics. Translators must also know and recognise the moral limits of their competence. Speaking fluently and knowing both source and target languages is no guarantee of accuracy of translation in a myriad of fields. The interaction which the Internet brings in our professional work is primarily and essentially a juncture of opportunity for both the client and the translator. The resulting translation or non-translation prove the quality of the principles being applied. The conscience of the translator should not exist suffering from a poverty of principles but rather should enjoy the luxury of comfort which those principles offer in adherence to truth, accuracy, fairness, and legality. Whether the translator is paid early or late, much or little, or not at all, is the economic reality of life. However, the translator must be able to stand over each text and say hand on heart ‘I really could not have done better. This, professionally, is a proud moment for me’. If such can be said, Internet interactions will have found translator ethics and professionalism at their very best. Ethics in the Translation and Interpreting CurriculumSurveying and Rethinking the Pedagogical LandscapeReport commissioned by the Higher Education Academy © Mona Baker, 2013 Contents1. Introduction 2. Ethics in Translator and Interpreter Education and Professional Codes of Practice 3. Incorporating Ethics in the Curriculum 4. Case Study: Introducing Ethics into the Curriculum at Leeds and University of East Anglia 5. Final Remarks and Recommendations 6. Recommended Reading 7. Other References 1. IntroductionThe growing pervasiveness of translation and interpreting in all domains of private and public life has been the subject of much commentary in the academic and professional worlds, and explains the unprecedented expansion in the number and range of academic programmes with ‘Translation’ and/or ‘Interpreting’ in their title in recent years. The UK, like other European countries, has witnessed a marked increase in the number of higher education institutions offering such courses under a variety of tiltes, including MA in Translation and Interpreting Studies, MA in Audiovisual Translation, MA in Sign Language Interperting, MA in Conference Interpreting and MA in Literary Translation, among others. The growth of activity in higher education reflects the fact that translation and interpreting are now increasingly recognised as vital activities and an indispensable part of the professional and social landscape. They have become central to promoting cultural and linguistic diversity and developing multilingual content in global media networks and the audiovisual marketplace. They have also become central to the delivery of institutional agendas in a wide range of settings, including supranational organisations such as the United Nations, the World Bank, the European Commission and the Football Association (FIFA), among others, as well as cultural, judicial, asylum, healthcare and social work services at the national level. These developments, and society’s increased reliance on translators and interpreters, have given rise to new forms of mediation that are subsumed under the term ‘translation’ or ‘interpreting’ and incorported into a wide range of training programmes. Examples include new forms of assistive mediation such as subtitling for the Deaf and hard-of-hearing and audio description for the blind, both of which aim to facilitate access to information and entertainment for sensory impaired members of the community and are now taught either as full MA level degrees in their own right or as part of more generic degrees in Translation Studies. Such rapid and far reaching changes in work environments have led to increased attention to questions of ethics in the academic literature on translation and interpreting in recent years (Chesterman 1997, Koskinen 2000, Jones 2004, Bermann and Wood 2005, Goodwin 2010, Baker and Maier 2011, Inghilleri 2011, among others). Although, with very few exceptions, this interest has not been reflected in the curricula for training translators and intepreters in any sustained way, the situation is now likely to change rapidly for a number of reasons, the most important of which concern the following: increased accountability; increased engagement by professional translators and interpreters with issues of ethics and a growing willingness among them to exercise moral judgement; greater visibility of translators and interpreters in the international arena as a result of the spread and intensity of violent conflict; and technological advances which have had a major impact on the profession. These are discussed below in some detail. 1.1 AccountabilityAccountability is now a central concern in all professions. It requires every professional and every citizen to demonstrate that he or she is cognizant of the impact of their behaviour on others, aware of its legal implications, and prepared to take responsibility for its consequences. While traditionally shielded from the consequences of their decisions by proclaimed values such as impartiality and neutrality which position them outside the interactions they mediate, translators and interpreters are now being held accountable for these consequences in ways that are forcing their educators to introduce more critical thinking and informed decision making into the curriculum. The arrest and trial of Mohamed Yousry in the US in 2005 is a case in point. Mohamed Yousry, an Arabic translator and interpreter appointed by the court to assist in a terrorism trial, was convicted by a New York jury of aiding and abetting an Egyptian terrorist organisation (U.S. v. Ahmed Abdel Sattar, Lynne Stewart, and Mohamed Yousry, 2005). The charge wasbased on prison rules designed to prevent high-risk inmates from communicating with the outside world. Yousry was held responsible for translating a letter from the defendant (Sheikh Omar Abdel Raman), at the instruction of the attorney (Lynne Stewart), which Stewart later released to the press. He had played no part in devising Stewart’s legal strategy and was not present when she contacted the press. As Hess explains (2012: 24), the ruling against Yousry was paradigm-changing for the interpreting industry. For the first time in US legal history, “an interpreter was held responsible for the actions of an attorney for whom he worked and for the content of the attorney-client conversations which he facilitated”. The case, and others that followed, reminded the profession that interpreters and translators can be held accountable not only for how they translate but also for the content, provenance and circulation of what they translate. [1] If they are to be held accountable in these respects, they must be trained to make ethically informed decisions for which they can knowingly assume responsiblity. 1.2 Professional Engagement with EthicsEspecially outside the domain of literary and religious translation, where engagement with issues of taste and morality is more likely to be found, practising translators and interpreters have traditionally been perceived as apolitical professionals whose priority is to earn a living by serving the needs of their fee paying clients. This is the ‘prototype’ of a professional translator or interpreter that is often presented to students. Indeed, one of the most influential theoretical frameworks that informs translator and interpreter training in many institutions across and beyond Europe, skopos theory (Vermeer 1989/2000, Reiß and Vermeer 1984/2013), assumes that decisions made in the course of translation must be guided by a ‘commission’ from the client (or initiator, or commissioner) who determines what purpose the translated text should serve and what audience it should address (Schäffner 2009: 121). Among other criticisms, this approach has been accused of turning translators and interpreters into “mercenary experts, able to fight under the flag of any purpose able to pay them” (Pym 1996: 338). In more recent years, however, practising translators and interpreters have begun to challenge this image of their profession by voicing their opinions on a variety of issues and debating the question of ethics explicitly, often to the amazement of clients who continue to think of them as apolitical and unengaged. As one medical translation agency put it in 2010, “[u]nless one’s work involves animal testing or abortion or a similar topic, translators are unlikely to get political about their work”. The agency was quick to note, however, that “the world, it is a-changing”. [2] The agency in question, Foreign Exchange Translations, decided to conduct a poll following a number of exchanges with translators who refused to take on certain assignments, either because they disagreed strongly with the content of the relevant texts or because of some aspect of the client’s profile. Foreign Exchange Translations framed the poll as follows: We recently received the following email from a medical translator who has worked for a long-standing device client of ours: “I’m not sure if you were aware, but there is a boycott in Mexico regarding travel, business, services, etc. related to Arizona and companies based there [3] It has come to my attention that [medical device company] is a company based in Arizona, U.S.A. I offer my sincerest apologies, but I have to terminate my contribution to this project due to my collaboration with this boycott. My timing is highly unfortunate. I realize this will affect our working relationship. I hope you can understand that had I known this earlier, I would have informed you appropriately.” It’s not like our team was living under a rock and hadn’t heard of recent events in Arizona but we were nevertheless surprised. What is your take on this? Is it the right thing to do to quit work for political reasons? Or should you suck it up and separate translation work from politics. The poll posed the following question to translators and interpreters who work for Foreign Exchange Translations: Do you refuse translations on ethical, moral, political, or religious grounds? It attracted 1571 responses. The results, and translators’ comments on the site, suggest that ethics is now a major concern for the profession. As shown in Figure 1, 18% of respondents chose ‘Yes, always’; 46% chose ‘Yes, sometimes’; 10% chose ‘No, but I wish I could afford to do that’; and only 26% answered ‘No, I have no qualms’. Figure 1: Full results of poll conducted by Foreign Exchange Translations [4] This level of engagement by practising translators and interpreters has had an impact on the corporate organisations that employ them. Professional interest in issues of ethics has led at least one translation company to call for a new approach to translator and interpreter training, one that nurtures a “profound understanding of professional ethics” (Bromberg and Jesionowski 2010). Bromberg and Jesionowski are co-designers of an Interpreter Online training programme at Bromberg and Associates, a translation agency located in southeast Michigan. [5] Such developments in the professional world cannot be ignored by higher education institutions, which should be leading pedagogical innovation rather than lagging behind the professional market. 1.3 Political ConflictThe final decade of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century have been marked by a number of major wars in which international humanitarian organisations and military forces have been extensively engaged: these include the Balkan wars, the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, the war in South Sudan, and more recently European intervention in Libya and Somalia. One feature of this widespread and persistent scenario has been a growing recognition of the involvement and visibility of interpreters and translators in high risk situations of violent conflict that demand the exercise of ethical judgement (Baker 2006, Inghilleri 2010). The impact of at least two related and important developments motivated by these events is beginning to be felt by translator and interpreter educators in many institutions. First, the international professional associations AIIC (Association Internationale des Interprètes de Conférence) and FIT (Fédération Internationale des Traducteurs) have recently initiated a project in collaboration with RedT, a non-profit organisation, to develop a Conflict Zone Field Guide designed to assist vulnerable interpreters working in war zones. This is a mjaor departure for AIIC, which exercises considerable influence on the content and direction of interpreter training programmes worldwide. As discussed later in this report (section 2), AIIC has traditionally focused on interpreter-client relations within a high profile, predominantly European, elite professional context, rather than ethically charged situations in which interpreters are often vulnerable and likely to confront a wide range of moral dilemmas. Second, and of more relevance to the current report, the Faculté de traduction et d’interprétation, University of Geneva, one of the oldest and most prestigious institutions involved in training translators and intepreters in the world, now offers virtual as well as face-to-face training to interpreters in crisis zones and is engaged in developing a professional code of ethics specifically for humanitarian interpeters. Its high profile project, InZone, [6] is run in collaboration with humanitarian organisations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross and Médecins sans Frontièrs, as well as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan. Such partners and settings draw attention to the ethical dimension of the translator’s and interpreter’s work and the impact of their behaviour on vulnerable populations. These two developments – one at the professional (AIIC/FIT/RedT initiative) and one at the academic level but involving non-academic partners (the InZone Project)– are important milestones on the road to effecting a more sustained engagement with the issue of ethics in translator and interpreter education worldwide. 1.4 Technological Advances

Terms and conditions do apply. Step 1 of 2. Overview Since you’ll be helping out Twitter (thanks again!) we want to let you know our ground rules. Please read the full agreement below before continuing. Here are some of the things you can expect to see: Among other things, Twitter plans to share the translations with the Twitter development community. We want to help make all of the other great Twitter apps, not just Twitter.com, available in your language. Crowdsourcing is a potentially useful means of reducing the digital divide, but its ethics have been questioned from the perspective of its impact on the profession, as well as the nature of the relationship it configures between the translator and the corporate body that commissions and benefits from the translator’s labour. As the extract from the Twitter ‘Translation Agreement’ above makes clear, this relationship is problematic. The above and other changes that have reconfigured the position of translators and interpreters in society and foregrounded both their vulnerability and their considerable influence on the lives of others call for a different approach to education than has hitherto been adopted. They demand a critical, ethically informed rexamination of what constitutes ethical behaviour in the field of translation and interpreting, and hence the type of training that should ideally be offered to translators and interpreters in higher education. 2. Ethics in Translator and Interpreter Education and Professional Codes of PracticeTranslator and interpreter education has traditionally sidestepped the issue of ethics. [9] At most, students are made aware of and encouraged to abide by existing professional codes of ethics, often referred to as codes of conduct or practice by organisations such as AIIC [10] (Association Internationale des Interprètes de Conférence) and the Translation and Interpreting Institute in the UK. [11] Professional codes generally focus on the relationship between the translator or interpreter and their client. They stress the need for impartiality, accuracy and efficiency, these being the traditional cornerstones of professional translation and interpreting, seen from the perspective of the service economy rather than social responsibility or human dignity. As Inghilleri (2009a:20) explains, Professional codes of ethics that attempt to demarcate the boundaries of utterances and texts from the social, political or historical contexts of their occurrence … emphasize compliance with principles of impartiality while minimizing the ethical challenges that interpreters and translators face in practice, especially where abuses of power or instances of injustice are in evidence. Although the primary duty of interpreters and translators to remain impartial is intended to protect the rights of all parties, there are circumstances when interpreters must weigh the rights of one individual against another to ensure that the objectives of all participants are given equal or adequate space within the interaction. The ability to balance one ethical obligation against another requires moments of genuine ethical insight. There is no guarantee that an individual interpreter or translator will accurately evaluate what is at stake within or beyond a particular encounter just as there is no certainty that a decision they make will produce a positive outcome.What is certain, however, is that interpreters and translators have a central role to play in the inevitable clashes that occur in the moral, social, and often violent, spaces of human interaction.