Our world in data

Our world in data

Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

The data on the coronavirus pandemic is updated daily.

Explore all metrics – including cases, deaths, testing, and vaccinations – in one place.

Get an overview of the pandemic for any country on a single page.

Download our complete dataset of COVID-19 metrics on GitHub. It’s open access and free for anyone to use.

Explore our global dataset on COVID-19 vaccinations.

See state-by-state data on vaccinations in the United States.

Explore the data on confirmed COVID-19 cases for all countries.

Explore the data on confirmed COVID-19 deaths for all countries.

Explore our data on COVID-19 testing to see how confirmed cases compare to actual infections.

See data on how many people are being hospitalized for COVID-19.

See how government policy responses – on travel, testing, vaccinations, face coverings, and more – vary across the world.

Learn what we know about the mortality risk of COVID-19 and explore the data used to calculate it.

Compare the number of deaths from all causes during COVID-19 to the years before to gauge the total impact of the pandemic on deaths.

Explore the global situation

Coronavirus Country Profiles

We built 207 country profiles which allow you to explore the statistics on the coronavirus pandemic for every country in the world.

In a fast-evolving pandemic it is not a simple matter to identify the countries that are most successful in making progress against it. For a comprehensive assessment, we track the impact of the pandemic across our publication and we built country profiles for 207 countries to study in depth the statistics on the coronavirus pandemic for every country in the world.

Each profile includes interactive visualizations, explanations of the presented metrics, and the details on the sources of the data.

Every country profile is updated daily.

Our 12 most visited country profiles

Every profile includes five sections:

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank a number of people in the development of this work: Carl Bergstrom, Bernadeta Dadonaite, Natalie Dean, Joel Hellewell, Jason Hendry, Adam Kucharski, Moritz Kraemer and Eric Topol for their very helpful and detailed comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this work. We thank Tom Chivers for his editorial review and feedback.

And we would like to thank the many hundreds of readers who give us feedback on this work. Your feedback is what allows us to continuously clarify and improve it. We very much appreciate you taking the time to write. We cannot respond to every message we receive, but we do read all feedback and aim to take the many helpful ideas into account.

Reuse our work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

Cite our work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this entry, please also cite the underlying data sources. This entry can be cited as:

Intelligence

Notice: This is only a preliminary collection of relevant material

The data and research currently presented here is a preliminary collection or relevant material. We will further develop our work on this topic in the future (to cover it in the same detail as for example our entry on World Population Growth).

If you have expertise in this area and would like to contribute, apply here to join us as a researcher.

In this entry we focus on how IQ has changed over time. The most common way of assessing intelligence is IQ testing.

All our interactive charts on Intelligence

The Flynn Effect: IQ gains over time

The ‘Flynn Effect’ describes the phenomenon that over time average IQ scores have been increasing. The change in IQ scores has been approximately three IQ points per decade. One major implications of this trend is that an average individual alive today would have an IQ of 130 by the standards of 1910, placing them higher than 98% of the population at that time. Equivalently, an individual alive in 1910 would have an IQ of 70 by today’s standards.

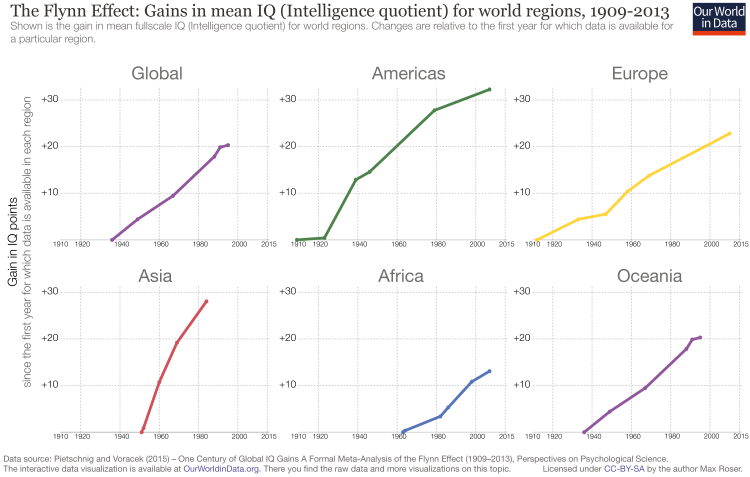

By world region

This visualization shows the gains in IQ that different world regions have made since the first year for which data is available for a particular region.

For each region this visualization shows the change since the first year for which there is data for that particular region. This means it is not possible to make comparisons between different regions and only possible to compare IQ scores over time.

By country

In a comprehensive study of the Flynn Effect, Jakob Pietschnig and Martin Voracek looked at 271 independent samples comprising 3,987,892 participants covering a time span of 105 years (1909–2013). 1

They find strong evidence to support the claim that IQ has been increasing substantially over time. 2 The paper discusses several explanations for the observed increases, namely education, exposure to technology and nutrition. For the definitions of the different IQ measures presented in the chart click here.

The charts show the estimated gain in average IQ for a selection of countries and world regions.

It is important to note that this is not a reflection of how intelligent a country/region is but instead how quickly advances were being made. As the visualization above it is only helpful for understanding changes over time. For more information on the drivers and composition of IQ gains, see our section here

The different measures of IQ displayed in the figure correspond to different types of intelligence.

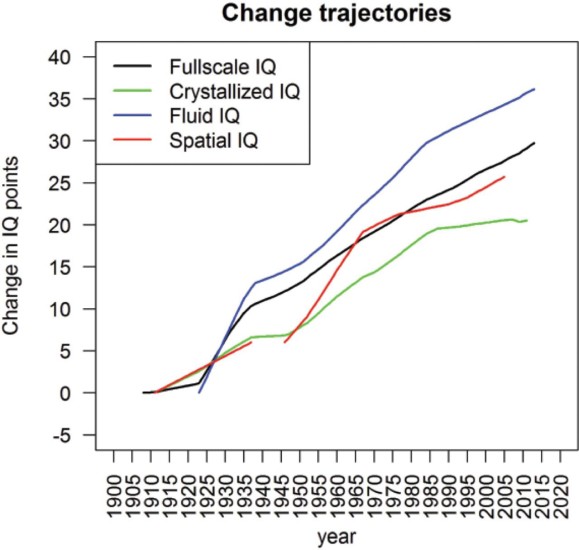

Domain-specific IQ gain trajectories, 1909-2013 – Pietschnig and Voracek 3

Click to open interactive version

Why is IQ changing?

Composition of IQ Gains

What has been driving the gains in intelligence?

There are many competing and complementary explanations: from nutrition and health improvements, greater levels of education, to the increasingly abstract nature of human existence.

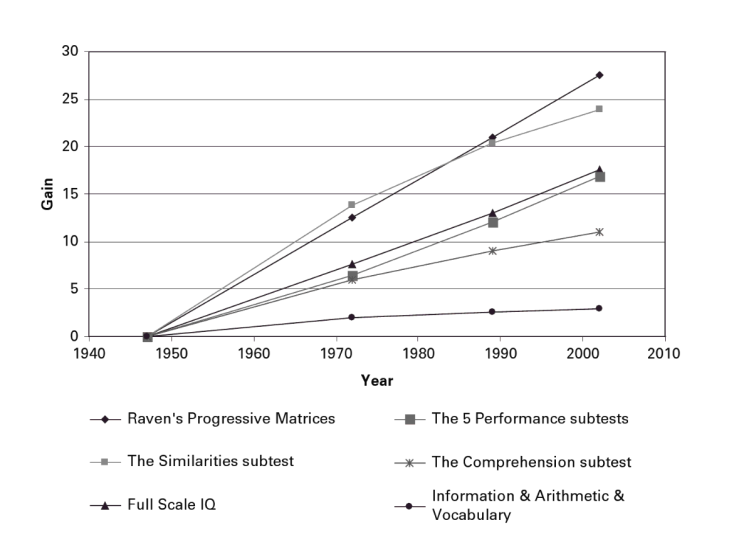

In James Flynn’s book What Is Intelligence?: Beyond the Flynn Effect, he decomposes the gains in IQ found for American children in the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) and finds that much of the gains have come from the subtests that focus on abstract thinking (similarities test and Raven’s progressive matrices). Only a small portion of the gains is due to improvements in knowledge of basic information, arithmetic and vocabulary. This observation would support the idea that increases in IQ have been driven by the changing way in which we live.

WISC IQ gains for America, 1947-2002 – Flynn (2007) 4

Domain-specific IQ gains

Researchers distinguish between intelligence across a range of domains:

The chart shows domain-specific IQ gain trajectories over the last century.

Domain-specific IQ gain trajectories, 1909-2013 – Pietschnig and Voracek 5

Alexander Luria’s Studies of Reasoning

Alexander Luria, a Russian neuropsychologist, conducted a series of interviews with headmen of villages in rural 1920s Russia as part of a study of reasoning. His research was published in a book titled Cognitive Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations in 1976. The following extract from James Flynn’s What is intelligence? is just one example of the types of responses Luria received from the villagers.

Today we have no difficulty freeing logic from concrete referents and reasoning about purely hypothetical situations. People were not always thus. Christopher Hallpike (1979) and Nick Mackintosh (2006) have drawn my attention to the seminal book on the social foundations of cognitive development by Luria (1976). His interviews with peasants in remote areas of the Soviet Union offer some wonderful examples. The dialogues paraphrased run as follows:

White bears and Novaya Zemlya (pp. 108-109):

Q: All bears are white where there is always snow; in Zovaya Zemlya there is always snow; what color are the bears there?

A: I have seen only black bears and I do not talk of what I have not seen.

Q: But what do my words imply?

A: If a person has not been there he can not say anything on the basis of words. If a man was 60 or 80 and had seen a white bear there and told me about it, he could be believed.

Population aging and The Flynn Effect

The effect of an aging population, especially in advanced economies, has an attenuating effect on average cognitive abilities over time.

Skirbekk et al. writing in Intelligence create projections of future cognitive abilities and find that if the Flynn effect reaches a saturation point, then average cognitive ability is expected to decline in the future. However, if the current Flynn effect persists, average intelligence will continue to rise in spite of an aging population. Consider the following simulations.

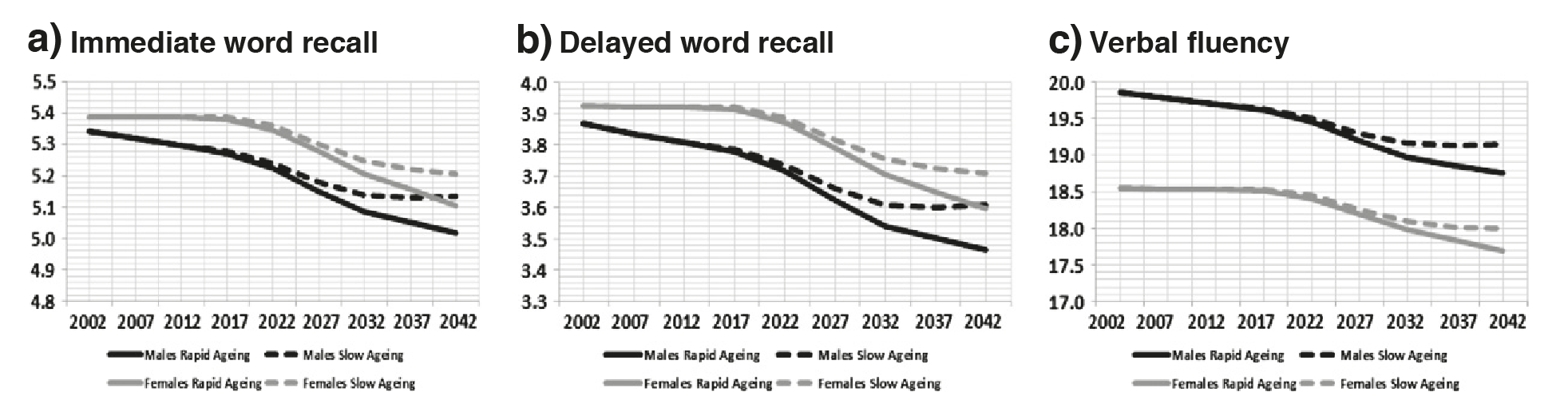

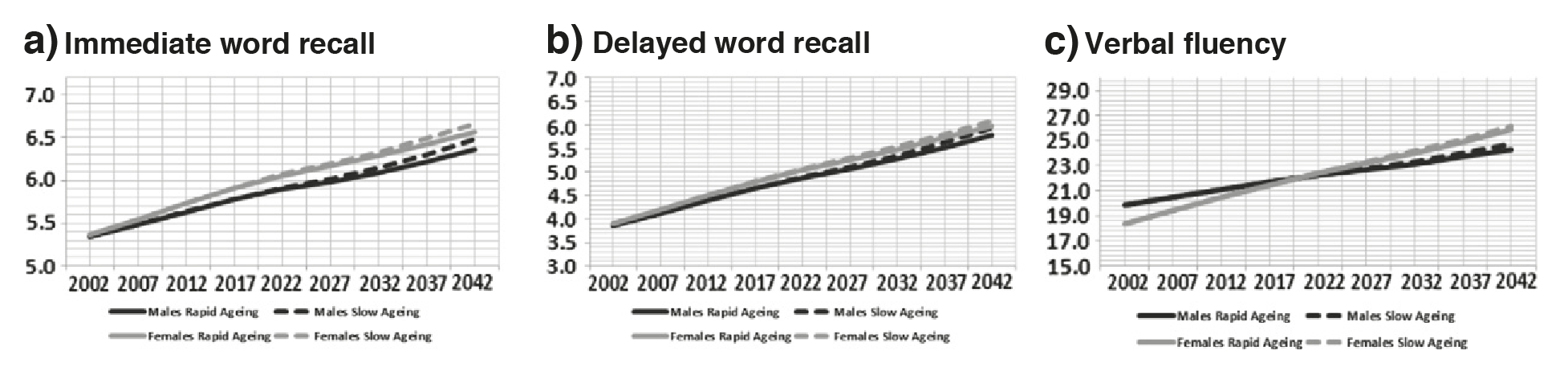

Cognitive score in scenario with no cohort effect and constant age variation, 2002-2042 – Skirbekk et al. (2013) 6

Projections of cognitive ability, age profile of cognition by cohort in scenario with continued improvement along cohort lines and constant lifespan trajectories – Skirbekk et al. (2013) 7

Disease Burden and IQ

Disease during pregnancy or early childhood can impair the cognitive development of children permanently. The driving force behind this theory is that if a child becomes seriously ill, the body transfers resources (energy) into fighting off the infection, reducing the amount left for brain development.

Nutrition and prosperity

An examination of the differences in IQ between two cohorts, one group born in 1921 and the other 15 years apart in 1936, finds substantial differences in IQ over their lifetimes. The study conducted by Staff et al. uses panel (longitudinal) data on the same groups of individuals. 8

All students born in either 1921 or 1936 and attending school in Scotland on June 1, 1932 or June 4, 1947 were made to sit intelligence examinations. The authors report that scores on the Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM) test increased annually by over one-half point. At age 77 (where there is an overlap in data) there is an estimated difference of 16.5 IQ points between the two cohorts, which is roughly three times larger than expected.

Dr Roger Staff explains that “those born in 1936 were children during the war and experienced food rationing. Although rationing meant that the food was not particularly appetising it was nutritious and probably superior to the older group. In addition, post-war political changes such as the introduction of the welfare state and a greater emphasis on education probably ensured better health and greater opportunities. Finally, in their thirties and forties the 1936 group experienced the oil boom which brought them and the city prosperity. Taken together, good nutrition, education and occupational opportunities have resulted in this life long improvement in their intelligence. Aberdeen has been good for their IQ!” More information on this research can be found here.

Endnotes

Pietschnig, Jakob, and Martin Voracek. “One Century of Global IQ Gains: A Formal Meta-Analysis of the Flynn Effect (1909-2010).” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2015, 282-306. doi:10.1177/1745691615577701.

In particular, the estimated increase is 0.41, 0.30, 0.28, and 0.21 IQ points annually for fluid, spatial, full-scale, and crystallized IQ test performance, respectively.

Pietschnig, Jakob, and Martin Voracek. “One Century of Global IQ Gains: A Formal Meta-Analysis of the Flynn Effect (1909-2010).” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2015, 282-306. doi:10.1177/1745691615577701. Available online here.

Flynn, James R. What is intelligence?: Beyond the Flynn effect. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Pietschnig, Jakob, and Martin Voracek. “One Century of Global IQ Gains: A Formal Meta-Analysis of the Flynn Effect (1909-2010).” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2015, 282-306. doi:10.1177/1745691615577701. Available online here.

S Vegard Skirbekk, Marcin Stonawski, Eric Bonsang, Ursula M. Staudinger, The Flynn effect and population aging, Intelligence, Volume 41, Issue 3, May–June 2013, Pages 169-177, ISSN 0160-2896. Available online here.

S Vegard Skirbekk, Marcin Stonawski, Eric Bonsang, Ursula M. Staudinger, The Flynn effect and population aging, Intelligence, Volume 41, Issue 3, May–June 2013, Pages 169-177, ISSN 0160-2896. Available online here.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Cases

We are grateful to everyone whose editorial review and expert feedback on this work helps us to continuously improve our work on the pandemic. Thank you. Here you find the acknowledgements.

The data on the coronavirus pandemic is updated daily.

Our work belongs to everyone

Explore the global data on confirmed COVID-19 cases

Select countries to show in all charts

This page has a large number of charts on the pandemic. In the box below you can select any country you are interested in – or several, if you want to compare countries.

All charts on this page will then show data for the countries that you selected.

Confirmed cases

What is the daily number of confirmed cases?

Related charts:

Which world regions have the most daily confirmed cases?

This chart shows the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases per day.

What is important to note about these case figures?

→ We provide more detail on these points in the section ‘Cases of COVID-19: background‘.

Five quick reminders on how to interact with this chart

Daily confirmed cases per million people

Differences in the population size between different countries are often large – it is insightful to compare the number of confirmed cases per million people.

Keep in mind that in countries that do very little testing the actual number of cases can be much higher than the number of confirmed cases shown here.

Three tips on how to interact with this map

What is the cumulative number of confirmed cases?

Related charts:

Which world regions have the most cumulative confirmed cases?

How do the number of tests compare to the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases? See them plotted against each other.

The previous charts looked at the number of confirmed cases per day – this chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed cases since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cumulative confirmed cases per million people

This chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed cases per million people.

Weekly and biweekly cases: where are confirmed cases increasing or falling?

Why is it useful to look at weekly or biweekly changes in confirmed cases?

For all global data sources on the pandemic, daily data does not necessarily refer to the number of new confirmed cases on that day – but to the cases reported on that day.

Since reporting can vary significantly from day to day – irrespectively of any actual variation of cases – it is helpful to look at changes from week to week. This provides a slightly clearer picture of where the pandemic is accelerating, slowing, or in fact reducing.

The maps shown here provide figures on weekly and biweekly confirmed cases: one set shows the number of confirmed cases per million people in the previous seven (or fourteen) days (the weekly or biweekly cumulative total); the other set shows the percentage change (growth rate) over these periods.

Click to open interactive version

Click to open interactive version

Click to open interactive version

Click to open interactive version

Global comparison: where are confirmed cases increasing most rapidly?

Simply looking at the cumulative total or daily number of confirmed cases does not allow us to understand or compare the speed at which these figures are rising.

The table here shows how long it has taken for the number of confirmed cases to double in each country for which we have data. The table also shows both the cumulative total and daily new number of confirmed cases, and how those numbers have changed over the last 14 days.

How you can interact with this table

You can sort the table by any of the columns by clicking on the column header.

Coronavirus sequences by variant

About this data

Our data on SARS-CoV-2 sequencing and variants is sourced from GISAID, a global science initiative that provides open-access to genomic data of SARS-CoV-2. We recognize the work of the authors and laboratories responsible for producing this data and sharing it via the GISAID initiative.

Khare, S., et al (2021) GISAID’s Role in Pandemic Response. China CDC Weekly, 3(49): 1049-1051. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2021.255 PMCID: 8668406

Elbe, S. and Buckland-Merrett, G. (2017) Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID’s innovative contribution to global health. Global Challenges, 1:33-46. doi:10.1002/gch2.1018 PMCID: 31565258

Shu, Y. and McCauley, J. (2017) GISAID: from vision to reality. EuroSurveillance, 22(13) doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494 PMCID: PMC5388101

We download aggregate-level data via CoVariants.org.

All countries report data on the results from sequenced samples every 14 days, although some of them may share partial data in advance. We obtain the share of each variant by dividing the number of sequences labelled for that variant by the total number of sequences. Since only a fraction of all cases are sequenced, this share may not reflect the complete breakdown of cases. In addition, recently-discovered or actively-monitored variants may be overrepresented, as suspected cases of these variants are likely to be sequenced preferentially or faster than other cases.

Click to open interactive version

Click to open interactive version

Click to open interactive version

Confirmed deaths and cases: our data source

Our World in Data relies on data from Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University dashboard and dataset is maintained by a team at its Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). It has been publishing updates on confirmed cases and deaths for all countries since January 22, 2020. A feature on the JHU dashboard and dataset was published in The Lancet in early May 2020. 1 This has allowed millions of people across the world to track the course and evolution of the pandemic.

JHU updates its data multiple times each day. This data is sourced from governments, national and subnational agencies across the world — a full list of data sources for each country is published on Johns Hopkins’s GitHub site. It also makes its data publicly available there.

Cases of COVID-19: background

How is a COVID-19 case defined?

In epidemiology, individuals who meet the case definition of a disease are often categorized on three different levels.

These definitions are often specific to the particular disease, but generally have some clear and overlapping criteria.

Cases of COVID-19 – as with other diseases – are broadly defined under a three-level system: suspected, probable and confirmed cases.

Typically, for a case to be confirmed, a person must have a positive result from laboratory tests. This is true regardless of whether they have shown symptoms of COVID-19 or not.

This means that the number of confirmed cases is lower than the number of probable cases, which is in turn lower than the number of suspected cases. The gap between these figures is partially explained by limited testing for the disease.

How are cases reported?

We have three levels of case definition: suspected, probable and confirmed cases. What is measured and reported by governments and international organizations?

International organizations – namely the WHO and European CDC – report case figures submitted by national governments. Wherever possible they aim to report confirmed cases, for two key reasons:

1. They have a higher degree of certainty because they have laboratory confirmation;

2. They help to provide standardised comparisons between countries.

However, international bodies can only provide figures as submitted by national governments and reporting institutions. Countries can define slightly different criteria for how cases are defined and reported. 4 Some countries have, over the course of the outbreak, changed their reporting methodologies to also include probable cases.

One example of this is the United States. Until 14 th April 2020 the US CDC provided daily reports on the number of confirmed cases. However, as of 14 th April, it now provides a single figure of cases: the sum of confirmed and probable cases.

Suspected case figures are usually not reported. The European CDC notes that suspected cases should not be reported at the European level (although countries may record this information for national records) but are used to understand who should be tested for the disease.

Reported new cases on a particular day do not necessarily represent new cases on that day

The number of confirmed cases reported by any institution – including the WHO, the ECDC, Johns Hopkins and others – on a given day does not represent the actual number of new cases on that date. This is because of the long reporting chain that exists between a new case and its inclusion in national or international statistics.

The steps in this chain are different across countries, but for many countries the reporting chain includes most of the following steps:

This reporting chain can take several days. This is why the figures reported on any given date do not necessarily reflect the number of new cases on that specific date.

The number of actual cases is higher than the number of confirmed cases

To understand the scale of the COVID-19 outbreak, and respond appropriately, we would want to know how many people are infected by COVID-19. We would want to know the actual number of cases.

However, the actual number of COVID-19 cases is not known. When media outlets claim to report the ‘number of cases’ they are not being precise and omit to say that it is the number of confirmed cases they speak about.

The actual number of cases is not known, not by us at Our World in Data, nor by any other research, governmental or reporting institution.

The number of confirmed cases is lower than the number of actual cases because not everyone is tested. Not all cases have a “laboratory confirmation”; testing is what makes the difference between the number of confirmed and actual cases.

All countries have been struggling to test a large number of cases, which means that not every person that should have been tested has been tested.

Since an understanding of testing for COVID-19 is crucial for an interpretation of the reported numbers of confirmed cases we have looked into the testing for COVID-19 in more detail.

You find our work on testing here. In a separate post we discuss how models of COVID-19 help us estimate the actual number of cases.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank a number of people in the development of this work: Carl Bergstrom, Bernadeta Dadonaite, Natalie Dean, Joel Hellewell, Jason Hendry, Adam Kucharski, Moritz Kraemer and Eric Topol for their very helpful and detailed comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this work. We thank Tom Chivers for his editorial review and feedback.

And we would like to thank the many hundreds of readers who give us feedback on this work. Your feedback is what allows us to continuously clarify and improve it. We very much appreciate you taking the time to write. We cannot respond to every message we receive, but we do read all feedback and aim to take the many helpful ideas into account.

Endnotes

The European CDC discusses the criteria for what constitutes a probable case, and a ‘close contact’ here.

See any Situation Report by the WHO – for example Situation Report 50.

The WHO also speaks of ‘suspected cases’ and ‘probable cases’, but the WHO Situation Reports do not provide figures on ‘probable cases’, and only report ‘suspected cases’ for Chinese provinces (‘suspected cases’ by country is not available).

In Situation Report 50 they define these as follows:

Suspect case

A. A patient with acute respiratory illness (fever and at least one sign/symptom of respiratory disease (e.g., cough, shortness of breath), AND with no other etiology that fully explains the clinical presentation AND a history of travel to or residence in a country/area or territory reporting local transmission (See situation report) of COVID-19 disease during the 14 days prior to symptom onset.

OR

B. A patient with any acute respiratory illness AND having been in contact with a confirmed or probable COVID19 case (see definition of contact) in the last 14 days prior to onset of symptoms;

OR

C. A patient with severe acute respiratory infection (fever and at least one sign/symptom of respiratory disease (e.g., cough, shortness breath) AND requiring hospitalization AND with no other etiology that fully explains the clinical presentation.

Probable case

A suspect case for whom testing for COVID-19 is inconclusive. Inconclusive being the result of the test reported by the laboratory.

The US, for example, uses the following definitions: “A confirmed case or death is defined by meeting confirmatory laboratory evidence for COVID-19. A probable case or death is defined by i) meeting clinical criteria AND epidemiologic evidence with no confirmatory laboratory testing performed for COVID-19; or ii) meeting presumptive laboratory evidence AND either clinical criteria OR epidemiologic evidence; or iii) meeting vital records criteria with no confirmatory laboratory testing performed for COVID19.”

Reuse our work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

Cite our work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this entry, please also cite the underlying data sources. This entry can be cited as:

About

Poverty, disease, hunger, climate change, war, existential risks, and inequality: The world faces many great and terrifying problems. It is these large problems that our work at Our World in Data focuses on.

Thanks to the work of thousands of researchers around the world who dedicate their lives to it, we often have a good understanding of how it is possible to make progress against the large problems we are facing. The world has the resources to do much better and reduce the suffering in the world.

We believe that a key reason why we fail to achieve the progress we are capable of is that we do not make enough use of this existing research and data: the important knowledge is often stored in inaccessible databases, locked away behind paywalls and buried under jargon in academic papers.

The goal of our work is to make the knowledge on the big problems accessible and understandable. As we say on our homepage, Our World in Data’s mission is to publish the “research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems”.

Why have we made this our mission?

This is the question our founder Max Roser answers in this text:

A publication to see the large global problems and the powerful changes that reshape our world

If you want to contribute to a better future you need to know the problems the world faces. To understand these problems the daily news is not enough. The news media focuses on events and therefore largely fails to report the two aspects that Our World in Data focuses on: the large problems that continue to confront us for centuries or much longer and the long-lasting, forceful changes that gradually reshape our world.

The criterion by which the news select what they focus our attention on is whether it is new. The criterion by which we at Our World in Data decide what to focus our attention on is whether it is important.

The front page of Our World in Data lists the same big global problems every day, because they matter every day. One of the biggest mistakes that the news media makes is to suggest that different things matter on different days.

To understand issues that are affecting billions, we need data. We need to carefully measure what we care about and make the results accessible in an understandable and public platform. This allows everyone to see the state of the world today and track where we are making progress, and where we are falling behind. The publication we are building has this goal. Through interactive data visualizations we can see how the world has changed; by summarizing the scientific literature we can understand why.

It is possible to change the world

To work towards a better future, we also need to understand how and why the world is changing.

The historical data and research shows that it is possible to change the world. Historical research shows that until a few generations ago around half of all newborns died as children. Since then the health of children has rapidly improved around the world and life expectancy has doubled in all regions. Progress is possible.

In other important ways global living conditions have improved as well. While we believe this is one of the most important facts to know about the world we live in, it is known by surprisingly few.

Instead, many believe that global living conditions are stagnating or getting worse and much of the news media’s reporting is doing little to challenge this perception. It is wrong to believe that one can understand the world by following the news alone and the media’s focus on single events and things that go wrong can mean that well-intentioned people who want to contribute to positive change become overwhelmed, hopeless, cynical and in the worst cases give up on their ideals. Much of our effort throughout these years has been dedicated to countering this threat.

Researching how it was possible to make progress against large problems in the past allows us to learn. Progress is possible, but it is not a given. If we want to know how to reduce suffering and tackle the world’s problems we should learn from what was successful in the past.

Comprehensive perspective on global living conditions and the earth’s environment

We take a broad perspective, covering an extensive range of aspects that matter for our lives. Measuring economic growth is not enough. The research publications on Our World in Data are dedicated to a large range of global problems in health, education, violence, political power, human rights, war, poverty, inequality, energy, hunger, and humanity’s impact on the environment. On the homepage we list all the global problems and important long-term changes that we have researched. The complete list of aspects that we eventually want to cover is longer still and can be found here.

As becomes obvious from our publication we always aim to provide a global perspective, but our focus are the living conditions of the worst-off.

Covering all of these aspects in one resource makes it possible to understand how long-run global trends are interlinked.

Measuring what matters

On the closely integrated website SDG-Tracker.org we present the data and research on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In 2015, all countries in the world signed up to reach the SDGs by 2030 and we built this site to track progress towards them. Our SDG-Tracker is a widely accessed publication that presents all the latest available data on the 232 SDG-Indicators with which the 17 Goals are assessed.

This is the core of our mission and extends beyond the SDGs. We all, the citizens of this world, are investing vast resources towards the ambitious goal of making the world a better place: we dedicate our lives to medical care and education, we are developing new technologies, we are spending large sums of money on infrastructure and the education of the next generation. What we do not do enough is to investigate whether these efforts are actually getting us closer to achieving our goals.

If the world wants to be serious about achieving progress we need to be much more serious about measuring what matters.

Our World in Data is based on the work of others – and should in turn be a base for others

The research we publish here is not only the work of our small team. Instead we rely on the work of a global community of scholars and wherever possible we see our role as presenting the best available research and data in an understandable and accessible way. Only when we find that important questions have not yet been answered do we do the necessary research ourselves and fill in the gaps.

Newton said, “If I have seen further than others, it is because I’ve stood on the shoulders of giants.” This is how science should work. Those who want to understand the world should be able to stand on the shoulders of those who came before them. A key part of our mission is therefore to build an infrastructure that makes research and data openly available and useful for all.

A publication to cover the long-run, built for the long-run

Making progress against the large problems that our world is facing will require dedicated work for a long time. We are therefore building a publication that aims to remain helpful for several decades: we regularly update our existing work as new research improves our understanding of the world; and we are building and expanding a central database, which allows us to continuously update the entire publication with the best available data.

Building the infrastructure to make data and research accessible and understandable

The web allows us to publish in a way that was unimaginable just a few years ago: distribution is free and research and data can be explored through interactive documents. Yet much of today’s research is published in a format that is essentially the same as that made available by Gutenberg’s printing press, 500 years ago.

To make research and data as accessible as possible we are a team in which researchers are collaborating with web developers. Together we are building the infrastructure that allows everyone in the world to understand how we make progress against our most pressing problems.

If you want to join us as a developer or researcher, see our Jobs page.

Our World in Data is a public good

We have big plans for the coming decades, but we are already having an impact. More than a million readers come to our site every month. Our work is very regularly covered by the media, our publication is informing many writers in their often widely read work, our writing is widely shared through social media, and we are regularly cited in top journals including Science and Nature.

For many relevant search queries – ‘CO2 emissions’, ‘world poverty’, ‘child mortality’, ‘population growth’ – we are one of the top search results in many parts of the world. And our work is commonly used as teaching material in schools and universities.

We design our work with the aim of generating an impact beyond what our team can achieve directly. By producing charts and data that can be freely downloaded and embedded in others’ work, we support and empower colleagues in policy, media and civil society also working on the problems we focus on.

This is why all the work we ever do is made available in its entirety as a public good:

We are funded through grants and reader donations

Reader donations are essential to our work, providing us with the stability and independence we need, so we can focus on showing the data and evidence we think everyone needs to know.

You can learn more about our funding in our How We’re Funded page, and you can help us do more by donating here – it will make a real difference.

Contact

You can always contact us at info@ourworldindata.org or fill in our Feedback form. If you have a question, you may find an answer in our Frequently asked questions. There we answer questions about copyright, citing our work, translating our work, our visualization software, and more.

Legal disclaimer

To the fullest extent permitted by the applicable law, Our World in Data offers the websites and services as-is and makes no representations or warranties of any kind concerning the websites or services, express, implied, statutory or otherwise, including, without limitation, warranties of title, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or noninfringement. Our World in Data does not warrant that the functions or content contained on the website or services will be uninterrupted or error-free, that defects will be corrected, or that Our World in Data servers are free of viruses or other harmful components. Our World in Data does not warrant or make any representation regarding use or the result of use of the content in terms of accuracy, reliability, or otherwise.

Except to the extent required by applicable law and then only to that extent, in no event will Our World in Data, or the people working on and related to this website (“the Our World in Data parties”) be liable to you on any legal theory for any incidental, direct, indirect, punitive, actual, consequential, special, exemplary or other damages, including without limitation, loss of revenue or income, lost profits, pain and suffering, emotional distress, cost of substitute goods or services, or similar damages suffered or incurred by you or any third party that arise in connection with the websites or services (or the termination thereof for any reason), even if the Our World in Data parties have been advised of the possibility of such damages.

The Our World in Data parties shall not be responsible or liable whatsoever in any manner for any content posted on the websites or services (including claims of infringement relating to content posted on the websites or services, for your use of the websites and services, or for the conduct of third parties whether on the websites, in connection with the services or otherwise relating to the websites or services.

Teaching Hub

Welcome to the Our World in Data Teaching Hub. Here you find information on how to use our work in teaching — and some materials we designed for teaching purposes.

If you have any questions or if you have suggestions to improve this page please write to us at info@ourworldindata.org or through our Feedback page.

Can I use Our World in Data for teaching?

Yes, you can use all our own work — charts, text, and data — for many teaching activities without any permission. This is because all our own work is licensed under a permissive ‘Creative Commons — by attribution’ license. You just need to credit Our World in Data and our underlying sources. That’s it.

This is different for material which is produced by others and which we only make available here. Charts and data that is produced by third parties remain subject to their original license terms.

How can I use Our World in Data to teach?

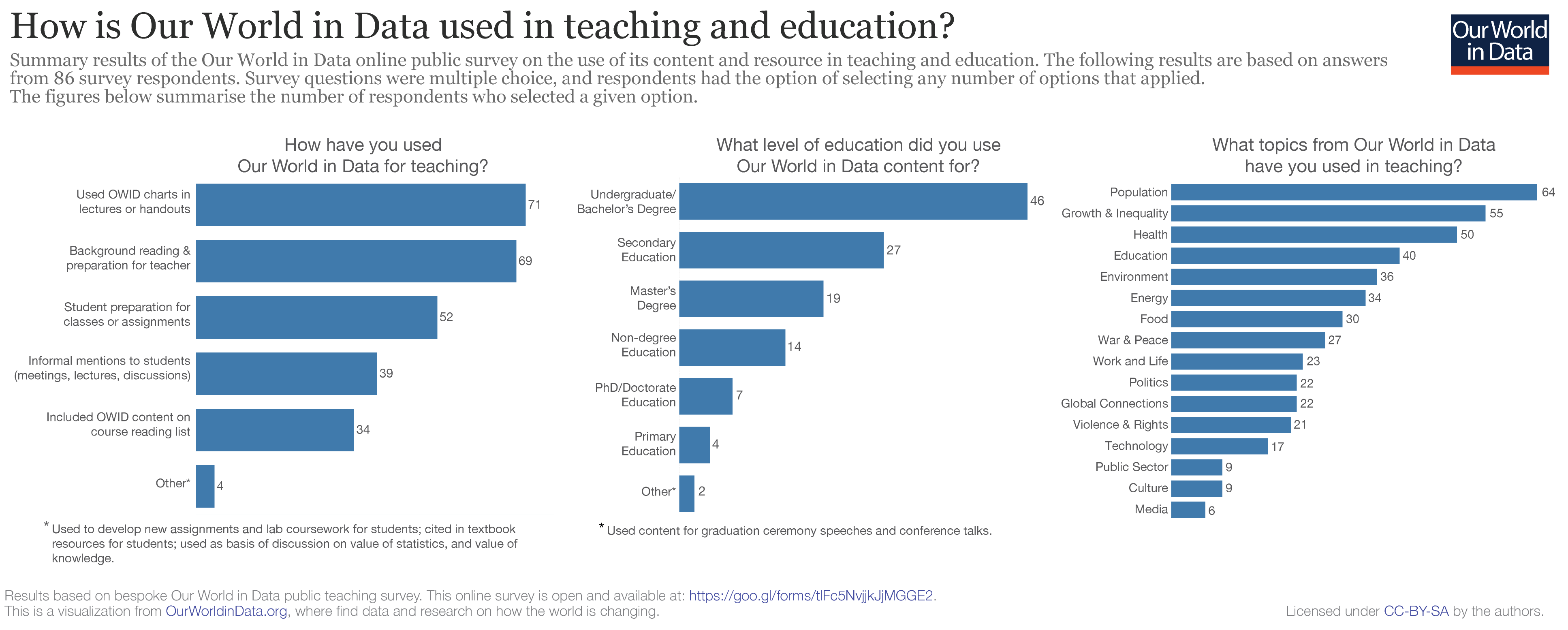

We know from emails and surveys that many teachers and professors use our work. This includes teachers from primary schools, secondary schools, and higher education institutions across the world, including leading universities such as Oxford, Cambridge, MIT, Berkeley, Harvard, and Stanford. Our work is also featured in many textbooks and learning tools, such as the CORE project.

Educators use our work to teach courses in many fields, ranging from physics, medicine, psychology and biology, to sustainable development, environmental sciences, economics, politics and public policy.

Drawing on their experiences, here are some ways you can use our work in teaching for both yourself and for your students:

If you already use our work to teach, we would love to hear from you.

You can fill out the teaching survey, write to us at info@ourworldindata.org or through our Feedback page. It would be great to know how our materials have been helpful, and what we can do to make it even more useful for you.

Do you have specific teaching materials?

For selected topics we have created interactive teaching notes, presentation slides, and chart sets, which we designed specifically for students and teachers. You are welcome to use, edit and share these materials for free.

These materials were created a few years ago, so some slides and graphs do not reflect our most recent data and research. We are working on updating and expanding the materials. As the interactive charts have usually not changed substantially, you might still find them useful. That is why we list them here, so you can find the most recent data available.

Extreme Poverty

What your students will learn:

Transport

Road travel

Passenger vehicle registrations by type

These interactive charts show the breakdown of new passenger vehicle registrations by type.

This is broken down by: petroleum; diesel; full hybrid (excluding plug-in hybrids); plug-in electric hybrids; and fully electric battery vehicles.

Click to open interactive version

Click to open interactive version

Electric vehicle registrations

This interactive chart shows the share of new passenger vehicle registrations that are battery electric vehicles. This does not include plug-in hybrid vehicles.

Click to open interactive version

This interactive chart shows the share of new passenger vehicle registrations that are battery electric plus plug-in hybrid vehicles.

Click to open interactive version

Carbon intensity of new passenger vehicles

This interactive chart shows the average carbon intensity of new passenger vehicles in each country.

This is measured as the average emissions of CO₂ (in grams) per kilometer travelled across all types of passenger vehicles.

Click to open interactive version

Fuel economy of new passenger vehicles

This interacrive chart shows the average fuel economy of new passenger vehicles in each country.

This is measured as the average liters consumed per 1000 kilometers travelled, across all types of passenger vehicles.

Click to open interactive version

Aviation

What share of global CO2 emissions come from aviation?

Flying is a highly controversial topic in climate debates. There are a few reasons for this.

The first is the disconnect between its role in our personal and collective carbon emissions. Air travel dominates a frequent traveller’s individual contribution to climate change. Yet aviation overall accounts for only 2.5% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. This is because there are large inequalities in how much people fly – many do not, or cannot afford to, fly at all [best estimates put this figure at around 80% of the world population – we will look at this in more detail in an upcoming article].

The second is how aviation emissions are attributed to countries. CO2 emissions from domestic flights are counted in a country’s emission accounts. International flights are not – instead they are counted as their own category: ‘bunker fuels’. The fact that they don’t count towards the emissions of any country means there are few incentives for countries to reduce them.

It’s also important to note that unlike the most common greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide, methane or nitrous oxide – non-CO2 forcings from aviation are not included in the Paris Agreement. This means they could be easily overlooked – especially since international aviation is not counted within any country’s emissions inventories or targets.

How much of a role does aviation play in global emissions and climate change? In this article we take a look at the key numbers that are useful to know.

Global aviation (including domestic and international; passenger and freight) accounts for:

The latter two numbers refer to 2018, and the first to 2016, the latest year for which such data are available.

Aviation accounts for 2.5% of global CO2 emissions

As we will see later in this article, there are a number of processes by which aviation contributes to climate change. But the one that gets the most attention is its contribution via CO2 emissions. Most flights are powered by jet gasoline – although some partially run on biofuels – which is converted to CO2 when burned.

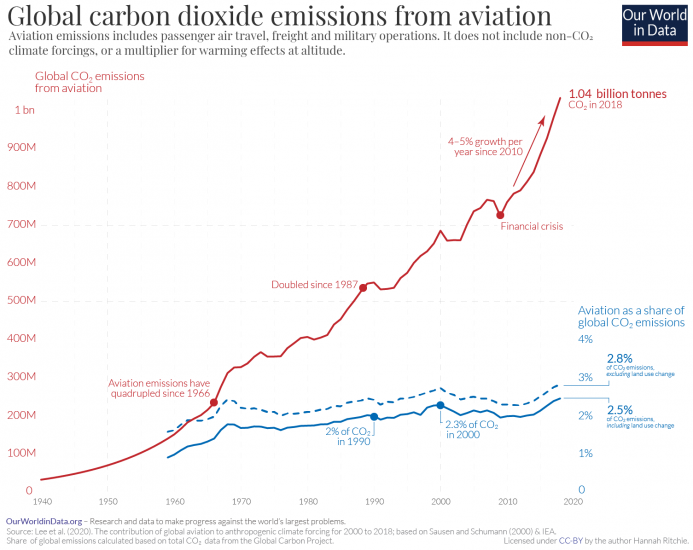

In a recent paper, researchers – David Lee and colleagues – reconstructed annual CO2 emissions from global aviation dating back to 1940. 1 This was calculated based on fuel consumption data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), and earlier estimates from Robert Sausen and Ulrich Schumann (2000). 2

The time series of global emissions from aviation since 1940 is shown in the accompanying chart. In 2018, it’s estimated that global aviation – which includes both passenger and freight – emitted 1.04 billion tonnes of CO2.

Aviation emissions have doubled since the mid-1980s. But, they’ve been growing at a similar rate as total CO2 emissions – this means its share of global emissions has been relatively stable: in the range of 2% to 2.5%. 5

Non-CO2 climate impacts mean aviation accounts for 3.5% of global warming

Aviation accounts for around 2.5% of global CO2 emissions, but it’s overall contribution to climate change is higher. This is because air travel does not only emit CO2: it affects the climate in a number of more complex ways.

As well as emitting CO2 from burning fuel, planes affect the concentration of other gases and pollutants in the atmosphere. They result in a short-term increase, but long-term decrease in ozone (O3); a decrease in methane (CH4); emissions of water vapour; soot; sulfur aerosols; and water contrails. While some of these impacts result in warming, others induce a cooling effect. Overall, the warming effect is stronger.

David Lee et al. (2020) quantified the overall effect of aviation on global warming when all of these impacts were included. 6 To do this they calculated the so-called ‘Radiative Forcing’. Radiative forcing measures the difference between incoming energy and the energy radiated back to space. If more energy is absorbed than radiated, the atmosphere becomes warmer.

In this chart we see their estimates for the radiative forcing of the different elements. When we combine them, aviation accounts for approximately 3.5% of effective radiative forcing: that is, 3.5% of warming.

Although CO2 gets most of the attention, it accounts for less than half of this warming. Two-thirds (66%) comes from non-CO2 forcings. Contrails – water vapor trails from aircraft exhausts – account for the largest share.

We don’t yet have the technologies to decarbonize air travel

Aviation’s contribution to climate change – 3.5% of warming, or 2.5% of CO2 emissions – is often less than people think. It’s currently a relatively small chunk of emissions compared to other sectors.

The key challenge is that it is particularly hard to decarbonize. We have solutions to reduce emissions for many of the largest emitters – such as power or road transport – and it’s now a matter of scaling them. We can deploy renewable and nuclear energy technologies, and transition to electric cars. But we don’t have proven solutions to tackle aviation yet.

There are some design concepts emerging – Airbus, for example, have announced plans to have the first zero-emission aircraft by 2035, using hydrogen fuel cells. Electric planes may be a viable concept, but are likely to be limited to very small aircraft due to the limitations of battery technologies and capacity.

Innovative solutions may be on the horizon, but they’re likely to be far in the distance.

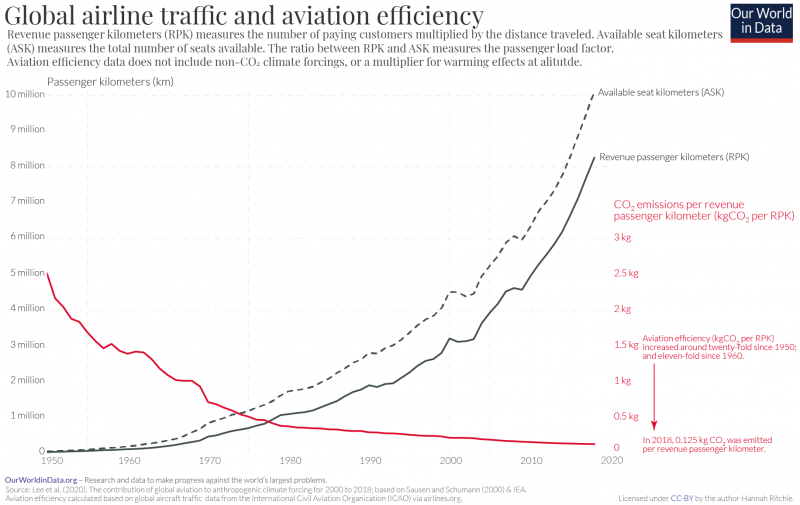

Appendix: Efficiency improvements means air traffic has increased more rapidly than emissions

Global emissions from aviation have increased a lot over the past half-century. However, air travel volumes increased even more rapidly.

Since 1950, aviation emissions increased almost seven-fold; since 1960 they’ve tripled. Air traffic volume – here defined as revenue passenger kilometers (RPK) traveled – increased by orders of magnitude more: almost 300-fold since 1950; and 75-fold since 1960 [you find this data in our interactive chart here]. 7

The much slower growth in emissions means aviation efficiency has seen massive improvements. In the chart we show both the increase in global airline traffic since 1950, and aviation efficiency, measured as the quantity of CO2 emitted per revenue passenger kilometer traveled. In 2018, approximately 125 grams of CO2 were emitted per RPK. In 1960, this was eleven-fold higher; in 1950 it was twenty-fold higher. Aviation has seen massive efficiency improvements over the past 50 years.

These improvements have come from several sources: improvements in the design and technology of aircraft; larger aircraft sizes (allowing for more passengers per flight); and an increase in how ‘full’ passenger flights are. This last metric is termed the ‘passenger load factor’. The passenger load factor measures the actual number of kilometers traveled by paying customers (RPK) as a percentage of the available seat kilometers (ASK) – the kilometers traveled if every plane was full. If every plane was full the passenger load factor would be 100%. If only three-quarters of the seats were filled, it would be 75%.

The global passenger load factor increased from 61% in 1950 to 82% in 2018 [you find this data in our interactive chart here].

Passenger vs. freight; domestic vs. international: where do aviation emissions come from?

Global aviation – both passenger flights and freight – emits around one billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) each year. This was equivalent to around 2.4% of CO2 emissions in 2018.

How do global aviation emissions break down?

The chart gives the answer. This data is sourced from the 2019 International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) report on global aviation. 8

Most emissions come from passenger flights – in 2018, they accounted for 81% of aviation’s emissions; the remaining 19% came from freight, the transport of goods.

Sixty percent of emissions from passenger flights come from international travel; the other 40% come from domestic (in-country) flights.

When we break passenger flight emissions down by travel distance, we get a (surprisingly) equal three-way split in emissions between short-haul (less than 1,500 kilometers); medium-haul (1,500 to 4,000 km); and long-haul (greater than 4,000 km) journeys.

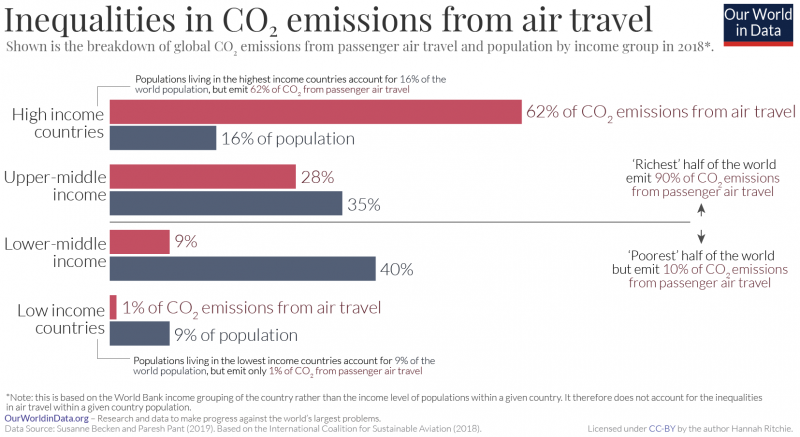

The richest half are responsible for 90% of air travel CO2 emissions

The global inequalities in how much people fly become clear when we compare aviation emissions across countries of different income levels. The ICCT split these emissions based on World Bank’s four income groups.

A further study by Susanne Becek and Paresh Pant (2019) compared the contribution of each income group to global air travel emissions versus its share of world population. 9 This comparison is shown in the visualization.

The ‘richest’ half of the world (high and upper-middle income countries) were responsible for 90% of air travel emissions. 10

Looking at specific income groups:

In an upcoming article we will look in more detail at the contribution of each country to global aviation emissions.

Where in the world do people have the highest carbon footprint from flying?

Aviation accounts for around 2.5% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. But if you are someone who does fly, air travel will make up a much larger share of your personal carbon footprint.

The fact that aviation is relatively small for global emissions as a whole, but of large importance for individuals that fly is due to large inequalities in the world. Most people in the world do not take flights. There is no global reliable figure, but often cited estimates suggest that more than 80% of the global population have never flown. 11

How do emissions from aviation vary across the world? Where do people have the highest footprint from flying?

Per capita emissions from domestic flights

The first and most straightforward comparison is to look at emissions from domestic aviation – that is, flights that depart and arrive in the same country.

This is easiest to compare because domestic aviation is counted in each country’s inventory of greenhouse gas emissions. International flights, on the other hand, are not attributed to specific countries – partly because of contention as to who should take responsibility (should it be the country of departure or arrival? What about layover flights?).

We see large differences in emissions from domestic flights across the world. In the United States the average person emits around 386 kilograms of CO2 each year from internal flights. This is followed by Australia (267 kg); Norway (209 kg); New Zealand (174 kg); and Canada (168 kg). Compare this with countries at the bottom of the table – many across Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe in particular emit less than one kilogram per person – just 0.8 kilograms; or 0.14 kilograms in Rwanda. For very small countries where there are no internal commercial flights, domestic emissions are of course, zero.

There are some obvious factors that explain some of these cross-country differences. Firstly, countries that are richer are more likely to have higher emissions because people can afford to fly. Second, countries that have a larger land mass may have more internal flights – and indeed we see a correlation between land area and domestic flight emissions; in small countries people are more likely to travel by other means such as car or train. And third, countries that are more geographically-isolated – such as Australia and New Zealand – may have more internal travel.

Click to open interactive version

Related charts:

Per capita emissions from international flights

Allocating emissions from international flights is more complex. International databases report these emissions separately as a category termed ‘bunker fuels’. The term ‘bunker fuel’ is used to describe emissions which come from international transport – either aviation or shipping.

Because they are not counted towards any particular country these emissions are also not taken into account in the goals that are set by countries in international treaties like the Kyoto protocol or the Paris Agreement. 14

But if we wanted to allocate them to a particular country, how would we do it? Who do emissions from international flights belong to: the country that owns the airline; the country of departure; the country of arrival?

Let’s first take a look at how emissions would compare if we allocated them to the country of departure. This means, for example, that emissions from any flight that departs from Spain are counted towards Spain’s total. In the chart here we see international aviation emissions in per capita terms.

Some of the largest emitters per person in 2018 were Iceland (3.5 tonnes of CO2 per person); Qatar (2.5 tonnes); United Arab Emirates (2.2 tonnes); Singapore (1.7 tonnes); and Malta (992 kilograms).

Again, we see large inequalities in emissions across the world – in many lower-income countries per capita emissions are only a few kilograms: 6 kilograms in India, 4 kilograms in Nigeria; and only 1.4 kilograms in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Click to open interactive version

Related charts:

Per capita emissions from international flights – adjusted for tourism

The above allocation of international aviation emissions to the country of departure raises some issues. It is not an accurate reflection of the local population of countries that rely a lot on tourism, for example. Most of the departing flights from these countries are carrying visiting tourists rather than locals.

One way to correct for this is to adjust these figures for the ratio of inbound to outbound travellers. This approach was applied in an analysis by Sola Zheng for the International Council on Clean Transportation. This attempts to distinguish between locals traveling abroad and foreign visitors traveling to that country on the same flight. 15 For example, if we calculated that Spain had 50% more incoming than outgoing travellers, we would reduce its per capita footprint from flying by 50%. If the UK had 75% more outgoing travellers than incoming, we’d increase its footprint by 75%.

We have replicated this approach and applied this adjustment to these figures by calculating the inbound:outbound tourist ratio based on flight departures and arrival data from the World Bank.

How does this affect per capita emissions from international flights? The adjusted figures are shown in the chart here.

As we would expect, countries which are tourist hotspots see the largest change. Portugal’s emissions, for example, fall from 388 to just 60 kilograms per person. Portugese locals are responsible for much fewer travel emissions than outgoing tourists. Spanish emissions fall from 335 to 77 kilograms per person.

On the other hand, countries where the locals travel elsewhere see a large increase. In the UK, they almost double from 422 to 818 kilograms.

Click to open interactive version

Per capita emissions from domestic and international flights

Let’s combine per capita emissions from domestic and international travel to compare the total footprint from flying.

This is shown in the interactive map [we’ve taken the adjusted international figures – you can find the combined figures without tourism-adjustment here].

The global average emissions from aviation were 103 kilograms. The inequality in emissions across the world becomes clear when this is broken down by country.

At the top of the table lies the United Arab Emirates – each person emits close to two tonnes – 1950 kg – of CO2 from flying each year. That’s 200 times the global average. This was followed by Singapore (1173 kilograms); Iceland (1070 kg); Finland (1000 kg); and Australia (878 kilograms).

To put this into perspective: a return flight (in economy class) from London to Dubai/United Arab Emirates would emit around one tonne of CO2. 16 So the two-tonne average for the UAE is equivalent to around two return trips to London.

In many countries, most people do not fly at all. The average Indian emits just 18 kilograms from aviation – this is much, much less than even a short-haul flight which confirms that most did not take a flight.

In fact, we can compare just the aviation emissions for the top countries to the total carbon footprint of citizens elsewhere. The average UAE citizen emits 1950 kilograms of CO2 from flying. This is the same as the total CO2 footprint of the average Indian (including everything from electricity to road transport, heating and industry). Or, to take a more extreme example, 200 times the total footprint of the average Nigerien, Ugandan or Ethiopian, which have per capita emissions of around 100 kilograms.

This again emphasises the large difference between the global average and the individual emissions of people who fly. Aviation contributes a few percent of total CO2 emissions each year – this is not insignificant, but far from being the largest sector to tackle. Yet from the perspective of the individual, flying is often one of the largest chunks of our carbon footprint. The average rich person emits tonnes of CO2 from flying each year – this is equivalent to the total carbon footprint of tens or hundreds of people in many countries of the world.

Click to open interactive version

Related charts:

Where in the world do people fly the most?

Domestic air travel

This interactive chart shows the average distance travelled per person through domestic air travel each year. This data is for passenger flights only and does not include freight.

Click to open interactive version

Related charts:

What share of global domestic air travel does each country account for?

International air travel

This interactive chart shows the average distance travelled per person through international air travel each year. This data is for passenger flights only and does not include freight.

Click to open interactive version

Related charts:

What share of global international air travel does each country account for?

Total air travel

This interactive chart shows the average distance travelled per person through domestic and international air travel each year. This data is for passenger flights only and does not include freight.

Click to open interactive version

Related charts:

What share of global air travel does each country account for?

This interactive chart shows the total rail travel in each country, measured in passenger-kilometers per year.

This includes passenger travel only and does not include freight.

Click to open interactive version

Energy intensity of transport

This chart shows the average energy intensity of transport across different modes of travel. It is measured as the average kilowatt-hours required per passenger-kilometer.

This data comes from the United States Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS). The energy intensity of public transport depends on the assumptions made about the capacity of transport modes i.e. how many passengers travel on a given train or bus journey. This data thererfore reflects average capacities in the United States, but will vary from country-to-country.

Click to open interactive version

CO2 emissions from transport

Per capita transport emissions from transport

This interactive shows the average per capita emissions of carbon dioxide from transport each year. This includes road, train, bus and domestic air travel but does not include international aviation and shipping.

Click to open interactive version

Total transport emissions

This interactive shows the emissions of carbon dioxide from transport each year. This includes road, train, bus and domestic air travel but does not include international aviation and shipping.

Click to open interactive version

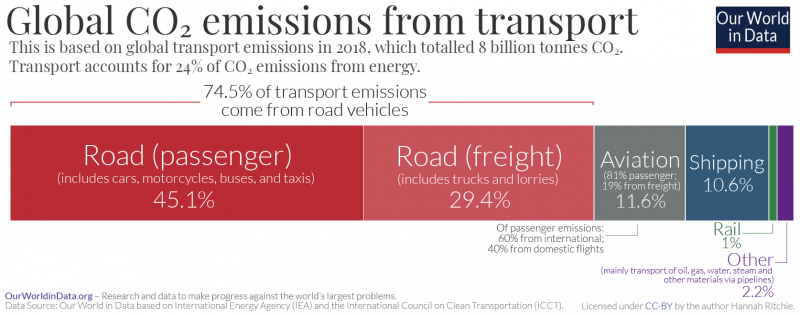

CO2 emissions by mode of transport

Transport accounts for around one-fifth of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions [24% if we only consider CO2 emissions from energy]. 17

How do these emissions break down? Is it cars, trucks, planes or trains that dominate?

In the chart here we see global transport emissions in 2018. This data is sourced from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Road travel accounts for three-quarters of transport emissions. Most of this comes from passenger vehicles – cars and buses – which contribute 45.1%. The other 29.4% comes from trucks carrying freight.

Since the entire transport sector accounts for 21% of total emissions, and road transport accounts for three-quarters of transport emissions, road transport accounts for 15% of total CO2 emissions.

Aviation – while it often gets the most attention in discussions on action against climate change – accounts for only 11.6% of transport emissions. It emits just under one billion tonnes of CO2 each year – around 2.5% of total global emissions [we look at the role that air travel plays in climate change in more detail in an upcoming article]. International shipping contributes a similar amount, at 10.6%.

Rail travel and freight emits very little – only 1% of transport emissions. Other transport – which is mainly the movement of materials such as water, oil, and gas via pipelines – is responsible for 2.2%.

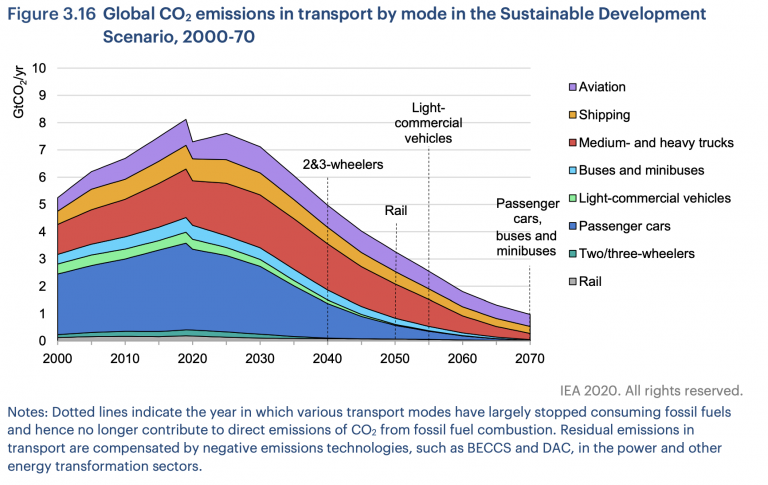

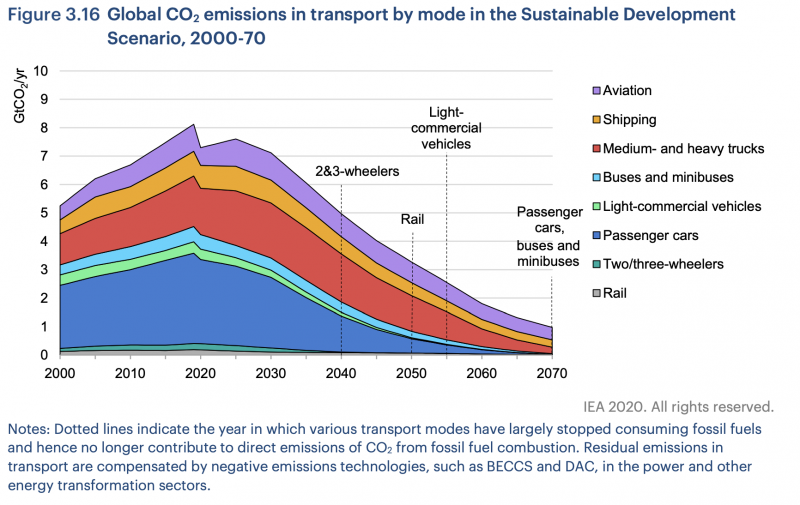

Towards zero-carbon transport: how can we expect the sector’s CO2 emissions to change in the future?

Transport demand is expected to grow across the world in the coming decades as the global population increases, incomes rise, and more people can afford cars, trains and flights. In its Energy Technology Perspectives report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects global transport (measured in passenger-kilometers) to double, car ownership rates to increase by 60%, and demand for passenger and freight aviation to triple by 2070. 18 Combined, these factors would result in a large increase in transport emissions.

But major technological innovations can help offset this rise in demand. As the world shifts towards lower-carbon electricity sources, the rise of electric vehicles offers a viable option to reduce emissions from passenger vehicles.

This is reflected in the IEA’s Energy Technology Perspective report. There it outlines its “Sustainable Development Scenario” for reaching net-zero CO2 emissions from global energy by 2070. The pathways for the different elements of the transport sector in this optimistic scenario are shown in the visualization.

We see that with electrification- and hydrogen- technologies some of these sub-sectors could decarbonize within decades. The IEA scenario assumes the phase-out of emissions from motorcycles by 2040; rail by 2050; small trucks by 2060; and although emissions from cars and buses are not completely eliminated until 2070, it expects many regions, including the European Union; United States; China and Japan to have phased-out conventional vehicles as early as 2040.

Other transport sectors will be much more difficult to decarbonize.

So, despite falling by three-quarters in the visualized scenario, emissions from these sub-sectors would still make transport the largest contributor to energy-related emissions in 2070. To reach net-zero for the energy sector as a whole, these emissions would have to be offset by ‘negative emissions’ (e.g. the capture and storage of carbon from bioenergy or direct air capture) from other parts of the energy system.

In the IEA’s net-zero scenario, nearly two-thirds of the emissions reductions come from technologies that are not yet commercially available. As the IEA states, “Reducing CO2 emissions in the transport sector over the next half-century will be a formidable task.” 22

Global CO2 emissions from transport in the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario to 2070 23

Endnotes

Lee, D. S., Fahey, D. W., Skowron, A., Allen, M. R., Burkhardt, U., Chen, Q., … & Gettelman, A. (2020). The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmospheric Environment, 117834.

The Global Carbon Budget estimated total CO2 emissions from all fossil fuels, cement production and land-use change to be 42.1 billion tonnes in 2018. This means aviation accounted for [1 / 42.1 * 100] = 2.5% of total emissions.

Global Carbon Project. (2019). Supplemental data of Global Carbon Budget 2019 (Version 1.0) [Data set]. Global Carbon Project. https://doi.org/10.18160/gcp-2019.

If we were to exclude land use change emissions, aviation accounted for 2.8% of fossil fuel emissions. The Global Carbon Budget estimated total CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement production to be 36.6 billion tonnes in 2018. This means aviation accounted for [1 / 36.6 * 100] = 2.8% of total emissions.

2.3% to 2.8% of emissions if land use is excluded.

Lee, D. S., Fahey, D. W., Skowron, A., Allen, M. R., Burkhardt, U., Chen, Q., … & Gettelman, A. (2020). The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmospheric Environment, 117834.

Airline traffic data comes from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) via Airlines for America. Revenue passenger kilometers (RPK) measures the number of paying passengers multiplied by their distance traveled.

Graver, B., Zhang, K., & Rutherford, D. (2019). CO2 emissions from commercial aviation, 2018. The International Council of Clean Transportation.

Note that this is based on categorisations from the average income level of countries, and does not take account of variation in income within countries. If we were to look at this distribution based on the income level of individuals rather than countries, the inequality in aviation emissions would be even larger.

There is no global database available on who in the world flies each year. Passenger information is maintained by private airlines. Therefore, deriving estimates of this exact percentage is challenging. The most-cited estimate I’ve seen on this is that around 80% of the world population have never flown. This figure seems to circle back to a quoted estimate from the Boeing CEO.

Even in some of the world’s richest countries, a large share of the population do not fly frequently. Gallup survey data from the United States suggests that in 2015, half of the population did not take a flight. Survey data from the UK provides similar estimates: 46% had not flown in the previous year.

Graver, B., Zhang, K., & Rutherford, D. (2019). CO2 emissions from commercial aviation, 2018. The International Council of Clean Transportation.

Note that this gives us mean per capita emissions, which does not account for in-country inequalities in the amount of flights people take.

A country with a ratio greater than one will have more incoming travellers than outgoing locals i.e. they are more of a hotspot for tourism.

We can calculate this by taking the standard CO2 conversion factors for travel, used in the UK greenhouse gas accounting framework. For a long-haul flight in economy class, around 0.079 kilograms of CO2 are emitted per passenger-kilometer. This means that you would travel around 12,600 kilometers to emit one tonne [1,000,000 / 0.079 kg = 12,626 kilometers]. Since we’re taking a return flight, the travel distance would be half of that figure: around 6300 kilometers. The direct distance from London to Dubai is around 5,500 kilometers. Depending on the flight path, it’s likely to be slightly longer than this, and in the range of 5500 to 6500 kilometers.

Note that in this case we’re looking at CO2 emissions without the extra warming effects of these emissions at high altitudes. This is to allow us to compare with the ICCT figures by country presented in this article. You find additional data on how the footprint of flying is impacted by non-CO2 warming effects here.

The World Resource Institute’s Climate Data Explorer provides data from CAIT on the breakdown of emissions by sector. In 2016, global CO2 emissions (including land use) were 36.7 billion tonnes CO2; emissions from transport were 7.9 billion tonnes CO2. Transport therefore accounted for 7.9 / 36.7 = 21% of global emissions.

The IEA looks at CO2 emissions from energy production alone – in 2018 it reported 33.5 billion tonnes of energy-related CO2 [hence, transport accounted for 8 billion / 33.5 billion = 24% of energy-related emissions.

Davis, S. J., Lewis, N. S., Shaner, M., Aggarwal, S., Arent, D., Azevedo, I. L., … & Clack, C. T. (2018). Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science, 360(6396).

Cecere, D., Giacomazzi, E., & Ingenito, A. (2014). A review on hydrogen industrial aerospace applications. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 39(20), 10731-10747.

Fulton, L. M., Lynd, L. R., Körner, A., Greene, N., & Tonachel, L. R. (2015). The need for biofuels as part of a low carbon energy future. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining, 9(5), 476-483.

Reuse our work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

Cite our work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this entry, please also cite the underlying data sources. This entry can be cited as:

Research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems

3269 charts across 297 topics

All free: open access and open source

Trusted in research and media

Find out how our work is used by journalists and researchers

Used in teaching

Find out how our work is used in teaching

Our latest work

We just published a new data explorer on the Environmental Impacts of Food

We just published our Air Pollution Data Explorer

The world is awful. The world is much better. The world can be much better.

People around the world have gained democratic rights, but some have many more rights than others

Five key findings from the 2022 UN Population Prospects

We just published our new Population and Demography Data Explorer

Subscribe to our newsletter

Follow us

Sustainable Development Goals Tracker

Is the world on track to reach the Sustainable Development Goals?

Teaching Hub

Slides, research, and visualizations for teaching and learning about global development

All our articles on global problems and global changes

Demographic Change

Population change

The world population increased from 1 billion in 1800 to 7.9 billion today.

Growth slowed from 2.2% per year 50 years ago to 1.0% per year today.

When and why did the world population grow? And how does rapid population growth come to an end?

World Population Growth

The UN projects that the global population will be 10.9 billion by 2100.

The population growth rate is then expected to be close to zero.

What can we expect for the future? What determines how large or small the world population will be?

Future Population Growth

The global median age increased from 22 years in 1970 to 31 years.

25% of the world are younger than 14 years. 9% are older than 65.

What is the age profile of populations around the world? How did it change and what will the age structure of populations look like in the future?

Age Structure

How does the number of men and women differ between countries? And why?

Gender Ratio

Life and death

The global average life expectancy is 73 years.

The global inequality is large.

When and why did the average age at which people die increase and how can we make further progress against early death?

Life Expectancy

5.2 million children younger than five die every year.

The global child mortality rate is 3.8%.

Why are children dying and what can be done to prevent it?

Child and Infant Mortality

The global average fertility rate is 2.4 children per woman.

In the last 50 years this rate has halved.

How does the number of children vary across the world and over time? What is driving the rapid global change?

Fertility Rate

Distribution of the World Population

56% of the world population live in urban areas.

In 1960 it was 34%.

The world population is moving to cities. Why is urbanization happening and what are the consequences?

Urbanization

Health

Explore the latest data on the Monkeypox outbreak.

Monkeypox

Around one-in-three children globally suffer from lead poisoning.

Lead pollution is a widespread problem that receives little attention. What is the scale of the problem and how can we tackle it?

Lead Pollution

The global average life expectancy is 73 years.

The global inequality is large.

When and why did the average age at which people die increase and how can we make further progress against early death?

Life Expectancy

5.2 million children younger than five die every year.

The global child mortality rate is 3.8%.

Why are children dying and what can be done to prevent it?

Child and Infant Mortality

295,000 women die from pregnancy-related causes every year.

What could be more tragic than a mother losing her life in the moment that she is giving birth to her newborn? Why are mothers dying and what can be done to prevent these deaths?

Maternal Mortality

57 million people die every year.

What do they die from?

How did the causes of death change over time?

Causes of death

The global burden of disease is large.

Per year 2.5 billion healthy life years are lost due to diseases, accidents, and premature deaths

How is the burden of disease distributed and how did it change over time?

Burden of Disease

10.1 million people die from cancer every year.

51% are younger than 70 years old.

Cancers are one of the leading causes of death globally. Are we making progress against cancer?

Cancer

An estimated 970 million people have a mental health disorder.

We provide a global overview of the prevalence of depression, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, and schizophrenia.

Mental Health

760,000 die from suicide per year.

59% are younger than 50 years old.

Every suicide is a tragedy. But they can be prevented.

Suicide

Health risks

6.7 million people die prematurely from air pollution each year.

Our overview on both indoor and outdoor air pollution.

Air Pollution

4.5 million people die prematurely from outdoor air pollution every year.

44% are younger than 70 years old.

Outdoor air pollution is one of the world’s largest health and environmental problems.

Outdoor Air Pollution

2.3 million people die prematurely from indoor air pollution every year.