World happiness report

World happiness report

World Happiness Report 2019

Abstract

The World Happiness Report is a landmark survey of the state of global happiness that ranks 156 countries by how happy their citizens perceive themselves to be. The World Happiness Report 2019 focuses on happiness and the community: how happiness has evolved over the past dozen years, with a focus on the technologies, social norms, conflicts and government policies that have driven those changes.

Read the Report

This is the 7th World Happiness Report. The first was released in April 2012 in support of a UN High level meeting on “Wellbeing and Happiness: Defining a New Economic Paradigm”. That report presented the available global data on national happiness and reviewed related evidence from the emerging science of happiness, showing that the quality of people’s lives can be coherently, reliably, and validly assessed by a variety of subjective well-being measures, collectively referred to then and in subsequent reports as “happiness.” Each report includes updated evaluations and a range of commissioned chapters on special topics digging deeper into the science of well-being, and on happiness in specific countries and regions. Often there is a central theme. This year we focus on happiness and community: how happiness has been changing over the past dozen years, and how information technology, governance and social norms influence communities.

The world is a rapidly changing place. Among the fastest changing aspects are those relating to how people communicate and interact with each other, whether in their schools and workplaces, their neighbourhoods, or in far-flung parts of the world. In last year’s report, we studied migration as one important source of global change, finding that each country’s life circumstances, including the social context and political institutions were such important sources of happiness that the international ranking of migrant happiness was almost identical to that of the native born. This evidence made a powerful case that the large international differences in life evaluations are driven by the differences in how people connect with each other and with their shared institutions and social norms.

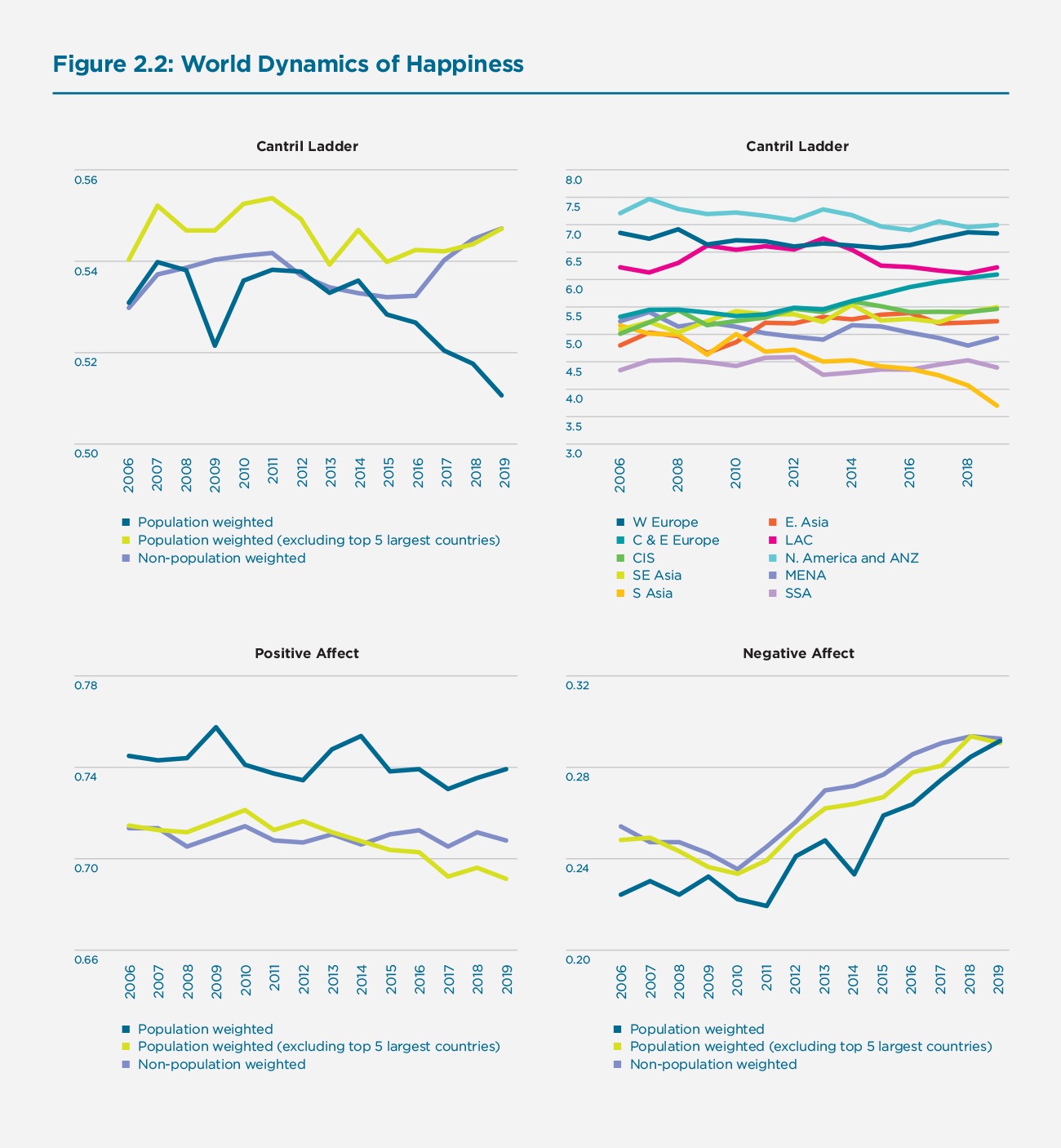

This year after presenting our usual country rankings of life evaluations, and tracing the evolution since 2005 of life evaluations, positive affect, negative affect, and our six key explanatory factors, we consider more broadly some of the main forces that influence happiness by changing the ways in which communities and their members interact with each other. We deal with three sets of factors:

Chapter 2 examines empirical linkages between a number of national measures of the quality of government and national average happiness. Chapter 3 reverses the direction of causality, and asks how the happiness of citizens affects whether and how people participate in voting.

The second special topic, covered in Chapter 4, is generosity and pro-social behaviour, important because of its power to demonstrate and creation communities that are happy places to live.

The third topic, covered by three chapters, is information technology. Chapter 5 discusses the happiness effects of digital technology use, Chapter 6 deals with big data, while Chapter 7 describes an epidemic of mass addictions in the United States, expanding on the evidence presented in Chapter 5.

Appendices & Data

Editors

John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey D. Sachs

Citation

This publication may be reproduced using the following reference: Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2019). World Happiness Report 2019, New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Acknowledgments

World Happiness Report management by Sharon Paculor, copy edit by Sweta Gupta, Sybil Fares and Ismini Ethridge. Design by Stislow Design and Ryan Swaney. The support of the Ernesto Illy Foundation and illycaffè is gratefully acknowledged.

The World Happiness Report is a publication of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, powered by the Gallup World Poll data.

The Report is supported by The Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s, The Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff, and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, The Happier Way Foundation, and The Regenerative Society Foundation.

The World Happiness Report was written by a group of independent experts acting in their personal capacities. Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization, agency or program of the United Nations.

World Happiness Report 2020

Abstract

The World Happiness Report is a landmark survey of the state of global happiness that ranks 156 countries by how happy their citizens perceive themselves to be. The World Happiness Report 2020 for the first time ranks cities around the world by their subjective well-being and digs more deeply into how the social, urban and natural environments combine to affect our happiness.

Read the Report

Foreword

This is the eighth World Happiness Report. We use this Foreword, the first we have had, to offer our thanks to all those who have made the Report possible over the past eight years, and to announce our expanding team of editors and partners as we prepare for our 9th and 10th reports in 2021 and 2022. The first seven reports were produced by the founding trio of co-editors assembled in Thimphu in July 2011 pursuant to the Bhutanese Resolution passed by the General Assembly in June 2011, that invited national governments to “give more importance to happiness and well-being in determining how to achieve and measure social and economic development.” The Thimphu meeting, chaired by Prime Minister Jigme Y. Thinley and Jeffrey D. Sachs, was called to plan for a United Nations High-Level Meeting on ‘Well-Being and Happiness: Defining a New Economic Paradigm’ held at the UN on April 2, 2012. The first World Happiness Report was prepared in support of that meeting, bringing together the available global data on national happiness and reviewing evidence from the emerging science of happiness.

The preparation of the first World Happiness Report was based in the Earth Institute at Columbia University, with the research support of the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, through their grants supporting research at the Vancouver School of Economics at UBC. The central base for the reports has since 2013 been the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and The Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University directed by Jeffrey D. Sachs. Although the editors and authors are volunteers, there are administrative and research support costs, covered most recently through a series of research grants from the Ernesto Illy Foundation and illycaffè.

Although the World Happiness Reports have been based on a wide variety of data, the most important source has always been the Gallup World Poll, which is unique in the range and comparability of its global series of annual surveys. The life evaluations from the Gallup World Poll provide the basis for the annual happiness rankings that have always spurred widespread interest. Readers may be drawn in by wanting to know how their nation is faring, but soon become curious about the secrets of life in the happiest countries. The Gallup team has always been extraordinarily helpful and efficient in getting each year’s data available in time for our annual launches on International Day of Happiness, March 20th. Right from the outset, we received very favourable terms from Gallup, and the very best of treatment. Gallup researchers have also contributed to the content of several World Happiness Reports. The value of this partnership was recognized by two Betterment of the Human Conditions Awards from the International Society for Quality of Life Studies. The first was in 2014 for the World Happiness Report, and the second, in 2017, went to the Gallup Organization for the Gallup World Poll.

From 2020, Gallup will be a full data partner, in recognition of the importance of the Gallup World Poll to the contents and reach of the World Happiness Report. We are proud to embody in this more formal way a history of co-operation stretching back beyond the first World Happiness Report to the start of the Gallup World Poll itself.

We have had a remarkable range of expert contributing authors over the years, and are deeply grateful for their willingness to share their knowledge with our readers. Their expertise is what assures the quality of the reports, and their generosity is what makes it possible. Thank you.

Our editorial team has been broadening over the years. In 2017, we added Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Haifang Huang, and Shun Wang as Associate Editors, joined in 2019 by Lara Aknin. From 2020, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve has become a co-editor, and the Oxford Wellbeing Research Centre thereby becomes a fourth research pole for the Report.

Sharon Paculor has for several years been the central figure in the production of the reports, and we now wish to recognize her long-standing dedication and excellent work with the title of Production Editor. The management of media has for many years been managed with great skill by Kyu Lee of the Earth Institute, and we are very grateful for all he does to make the reports widely accessible. Ryan Swaney has been our web designer since 2013, and Stislow Design has done our graphic design work over the same period. Juliana Bartels, a new recruit this year, has provided an important addition to our editorial and proof-reading capacities. All have worked on very tight timetables with great care and friendly courtesy.

Our group of partners has also been enlarged, and now includes the Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, and Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s.

Our data partner is Gallup, and institutional sponsors now include the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE, the Vancouver School of Economics at UBC, and the Wellbeing Research Centre at Oxford.

For all of these contributions, whether in terms of research, data, or grants, we are enormously grateful.

John Helliwell, Richard Layard, Jeffrey D. Sachs, and Jan Emmanuel De Neve, Co-Editors; Lara Aknin, Haifang Huang and Shun Wang, Associate Editors; and Sharon Paculor, Production Editor

Appendices & Data

Editors

John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard, Jeffrey D. Sachs, and Jan Emmanuel De Neve, Co-Editors; Lara Aknin, Haifang Huang and Shun Wang, Associate Editors; and Sharon Paculor, Production Editor

Citation

Helliwell, John F., Richard Layard, Jeffrey Sachs, and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, eds. 2020. World Happiness Report 2020. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network

The World Happiness Report is a publication of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, powered by the Gallup World Poll data.

The Report is supported by The Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s, The Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff, and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, The Happier Way Foundation, and The Regenerative Society Foundation.

The World Happiness Report was written by a group of independent experts acting in their personal capacities. Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization, agency or program of the United Nations.

World Happiness Report 2022

Abstract

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the World Happiness Report, which uses global survey data to report how people evaluate their own lives in more than 150 countries worldwide. The World Happiness Report 2022 reveals a bright light in dark times. The pandemic brought not only pain and suffering but also an increase in social support and benevolence. As we battle the ills of disease and war, it is essential to remember the universal desire for happiness and the capacity of individuals to rally to each other’s support in times of great need.

Read the Report

Appendices & Data

Editors

John Helliwell, Richard Layard, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Lara B. Aknin, Shun Wang; and Sharon Paculor, Production Editor

Citation

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., Sachs, J. D., De Neve, J.-E., Aknin, L. B., & Wang, S. (Eds.). (2022). World Happiness Report 2022. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

The World Happiness Report is a publication of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, powered by the Gallup World Poll data.

The Report is supported by The Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s, The Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff, and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, The Happier Way Foundation, and The Regenerative Society Foundation.

The World Happiness Report was written by a group of independent experts acting in their personal capacities. Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization, agency or program of the United Nations.

World Happiness Report 2021

Abstract

The World Happiness Report 2021 focuses on the effects of COVID-19 and how people all over the world have fared. Our aim was two-fold, first to focus on the effects of COVID-19 on the structure and quality of people’s lives, and second to describe and evaluate how governments all over the world have dealt with the pandemic. In particular, we try to explain why some countries have done so much better than others.

Read the Report

Foreword

This is the ninth World Happiness Report. We use this Foreword to offer our thanks to all those who have made the Report possible over the past nine years and to thank our team of editors and partners as we prepare for our decennial report in 2022.

The first eight reports were produced by the founding trio of co-editors assembled in Thimphu in July 2011 pursuant to the Bhutanese Resolution passed by the General Assembly in June 2011 that invited national governments to “give more importance to happiness and well-being in determining how to achieve and measure social and economic development.” The Thimphu meeting, chaired by Prime Minister Jigmi Y. Thinley and Jeffrey D. Sachs, was called to plan for a United Nations High-Level Meeting on ‘Well-Being and Happiness: Defining a New Economic Paradigm’ held at the UN on April 2, 2012. The first World Happiness Report was prepared in support of that meeting and reviewing evidence from the emerging science of happiness.

The preparation of the first World Happiness Report was based in the Earth Institute at Columbia University, with the Centre for Economic Performance’s research support at the LSE and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, through their grants supporting research at the Vancouver School of Economics at UBC. The central base for the reports has since 2013 been the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and The Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, directed by Jeffrey D. Sachs. Although the editors and authors are volunteers, there are administrative, and research support costs covered most recently through a series of grants from The Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, The Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff, and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, The Happier Way Foundation, Indeed, and Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s.

As noted within the report, this year has been one like no other. The Gallup World Poll team has faced significant challenges in collecting responses this year due to COVID-19, and we much appreciate their efforts to provide timely data for this Report. We were also grateful for the World Risk Poll data provided by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation as part of their risk supplement to the Gallup World Poll in 2019. We also greatly appreciate the life satisfaction data collected during 2020 as part of the Covid Data Hub run in 2020 by Imperial College London and the YouGov team. These data partnerships are all much appreciated.

Although the World Happiness Reports are based on a wide variety of data, the most important source has always been the Gallup World Poll, which is unique in the range and comparability of its global series of annual surveys.

The life evaluations from the Gallup World Poll provide the basis for the annual happiness rankings that have always sparked widespread interest. Readers may be drawn in by wanting to know how their nation is faring but soon become curious about the secrets of life in the happiest countries. The Gallup team has always been extraordinarily helpful and efficient in getting each year’s data available in time for our annual launches on International Day of Happiness, March 20th. Right from the outset, we received very favourable terms from Gallup and the very best of treatment. Gallup researchers have also contributed to the content of several World Happiness Reports. The value of this partnership was recognized by two Betterment of the Human Conditions Awards from the International Society for Quality of Life Studies. The first was in 2014 for the World Happiness Report, and the second, in 2017, went to the Gallup Organization for the Gallup World Poll.

Since last year, Gallup has been a full data partner in recognition of the Gallup World Poll’s importance to the contents and reach of the World Happiness Report. We are proud to embody in this more formal way a history of co-operation stretching back beyond the first World Happiness Report to the start of the Gallup World Poll itself. COVID-19 has posed unique problems for data collection, and the team at Gallup has been extremely helpful in building the largest possible sample of data in time for inclusion in this report. They have gone the extra mile, and we thank them for it.

We have had a remarkable range of expert contributing authors over the years and are deeply grateful for their willingness to share their knowledge with our readers. Their expertise assures the quality of the reports, and their generosity is what makes it possible. Thank you.

Our editorial team has evolved over the years. In 2017, we added Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Haifang Huang, and Shun Wang as Associate Editors, joined in 2019 by Lara Aknin. In 2020, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve became a co-editor, and the Oxford Wellbeing Research Centre thereby became a fourth research pole for the Report. In 2021, Haifang Huang stepped down as an Associate Editor, following four years of much-appreciated service. He has kindly agreed to continue as co-author of Chapter 2, where his contributions have been crucial since 2015.

Sharon Paculor has continued her excellent work as the Production Editor. For many years, Kyu Lee of the Earth Institute handled media management with great skill, and we are very grateful for all he does to make the reports widely accessible. Ryan Swaney has been our web designer since 2013, and Stislow Design has done our graphic design work over the same period.

The team at the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, Sybil Fares, Juliana Bartels, Meredith Harris, and Savannah Pearson, and Jesse Thorson, have provided an essential addition to our editorial and proof-reading capacities. All have worked on very tight timetables with great care and friendly courtesy.

Our data partner is Gallup, and institutional sponsors include the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE, the Vancouver School of Economics at UBC, and the Wellbeing Research Centre at Oxford.

Whether in terms of research, data, or grants, we are enormously grateful for all of these contributions.

John Helliwell, Richard Layard, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Lara Aknin, Shun Wang; and Sharon Paculor, Production Editor

Appendices & Data

Editors

John Helliwell, Richard Layard, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Lara Aknin, Shun Wang; and Sharon Paculor, Production Editor

World Happiness Report 2018

Abstract

The World Happiness Report is a landmark survey of the state of global happiness. The World Happiness Report 2018, ranks 156 countries by their happiness levels, and 117 countries by the happiness of their immigrants. The main focus of this year’s report, in addition to its usual ranking of the levels and changes in happiness around the world, is on migration within and between countries.

Read the Report

The overall rankings of country happiness are based on the pooled results from Gallup World Poll surveys from 2015-2017, and show both change and stability. There is a new top ranking country, Finland, but the top ten positions are held by the same countries as in the last two years, although with some swapping of places. Four different countries have held top spot in the four most recent reports- Denmark, Switzerland, Norway and now Finland.

All the top countries tend to have high values for all six of the key variables that have been found to support well-being: income, healthy life expectancy, social support, freedom, trust and generosity. Among the top countries, differences are small enough that that year-to-year changes in the rankings are to be expected.

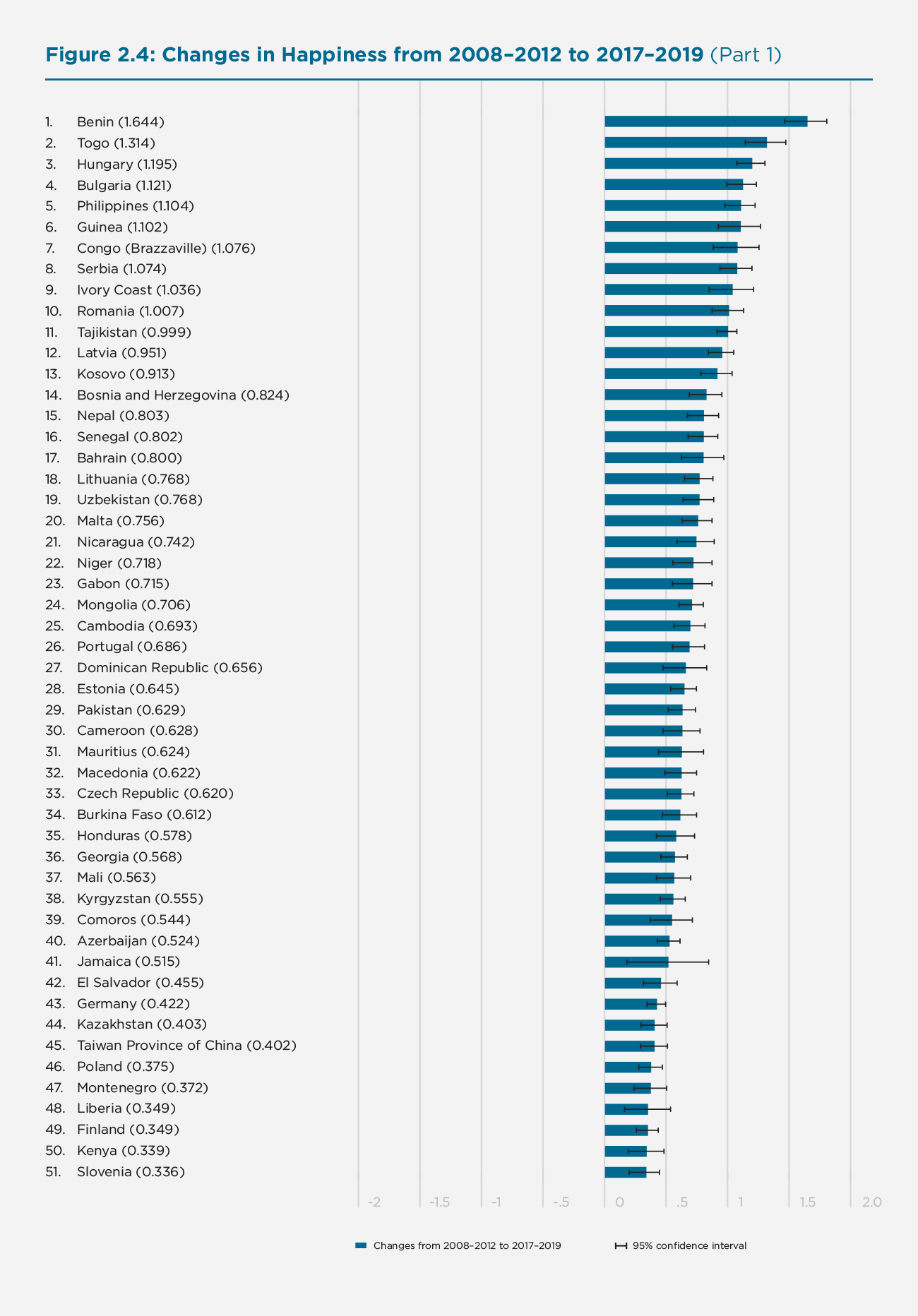

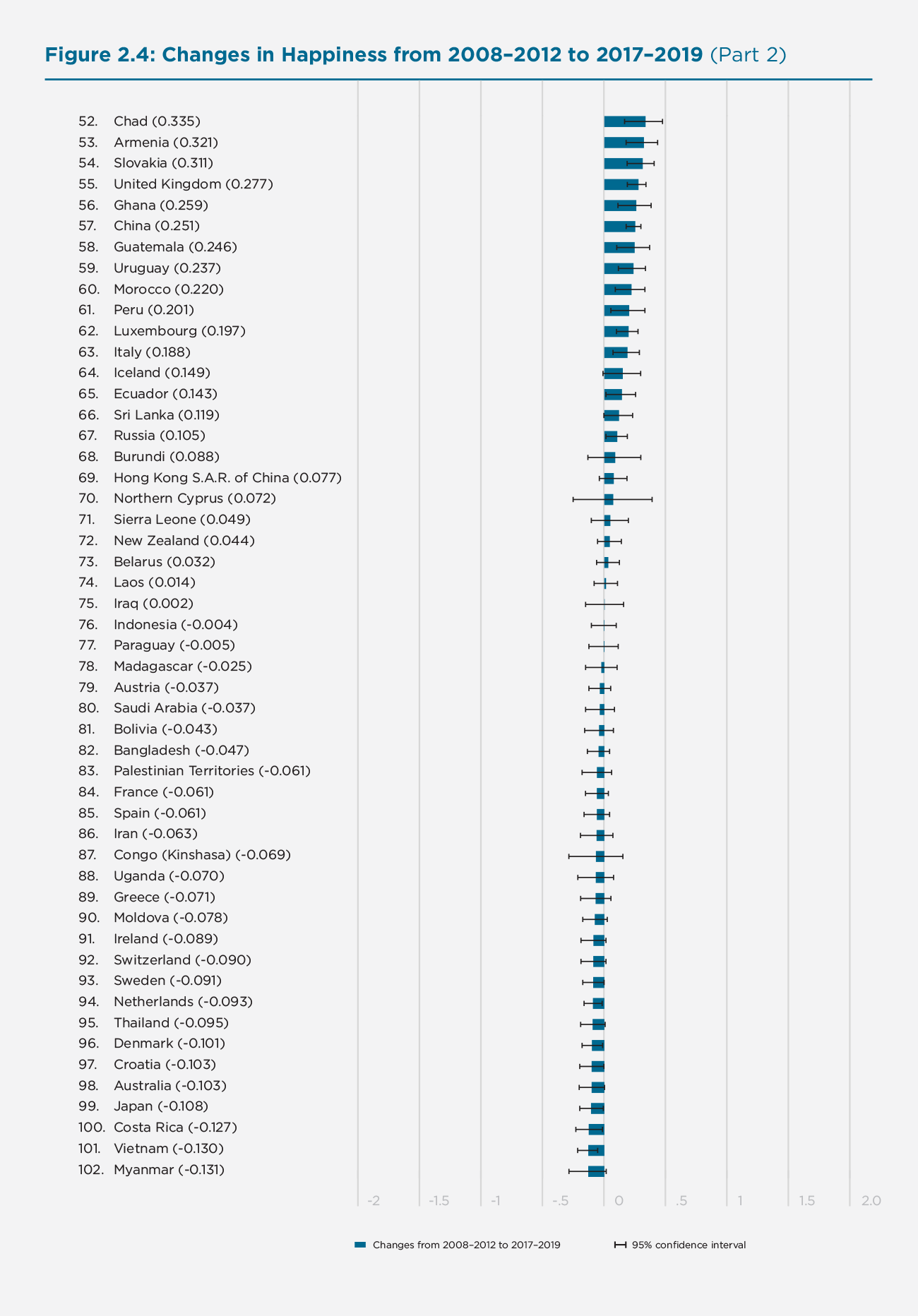

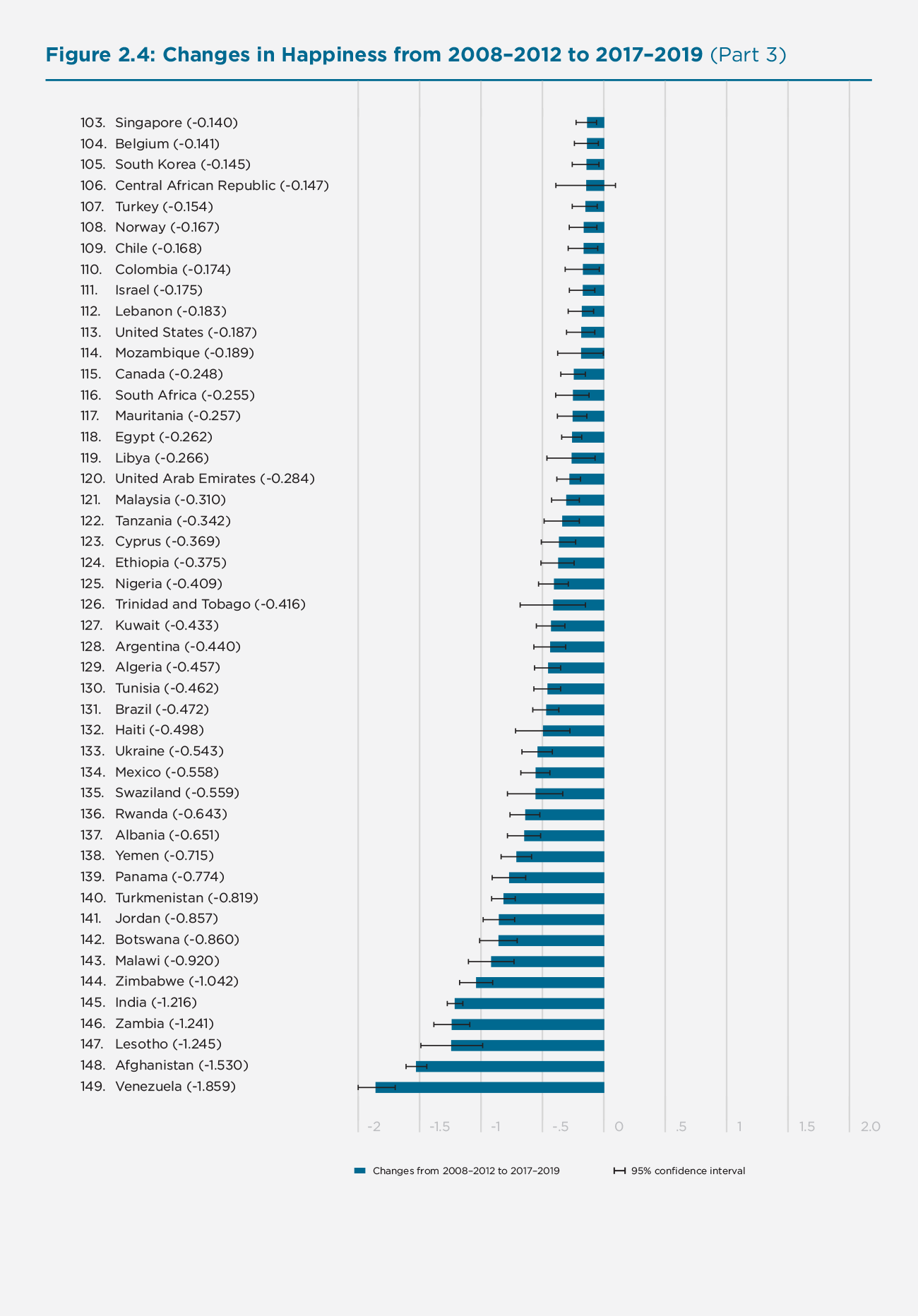

The analysis of happiness changes from 2008-2010 to 2015-2015 shows Togo as the biggest gainer, moving up 17 places in the overall rankings from the last place position it held as recently as in the 2015 rankings. The biggest loser is Venezuela, down 2.2 points on the 0 to 10 scale.

Five of the report’s seven chapters deal primarily with migration, as summarized in Chapter 1. For both domestic and international migrants, the report studies not just the happiness of the migrants and their host communities, but also of those left behind, whether in the countryside or in the source country. The results are generally positive.

Perhaps the most striking finding of the whole report is that a ranking of countries according to the happiness of their immigrant populations is almost exactly the same as for the rest of the population. The immigrant happiness rankings are based on the full span of Gallup data from 2005 to 2017, sufficient to have 117 countries with more than 100 immigrant respondents.

The ten happiest countries in the overall rankings also ll ten of the top eleven spots in the ranking of immigrant happiness. Finland is at the top of both rankings in this report, with the happiest immigrants, and the happiest population in general.

The closeness of the two rankings shows that the happiness of immigrants depends predominantly on the quality of life where they now live, illustrating a general pattern of convergence. Happiness can change, and does change, according to the quality of the society in which people live. Immigrant happiness, like that of the locally born, depends on a range of features of the social fabric, extending far beyond the higher incomes traditionally thought to inspire and reward migration. The countries with the happiest immigrants are not the richest countries, but instead the countries with a more balanced set of social and institutional supports for better lives.

While convergence to local happiness levels is quite rapid, it is not complete, as there is a ‘footprint’ effect based on the happiness in each source country. This effect ranges from 10% to 25%. This footprint effect, explains why immigrant happiness is less than that of the locals in the happiest countries, while being greater in the least happy countries.

A very high proportion of the international differences in immigrant happiness (as shown in Chapter 2), and of the happiness gains for individual migrants (as studied in Chapters 3 and 5) are thus explained by local happiness and source country happiness.

The explanation becomes even more complete when account is taken of international differences in a new Gallup index of migrant acceptance, based on local attitudes towards immigrants, as detailed in an Annex to the Report. A higher value for migrant acceptance is linked to greater happiness for both immigrants and the native-born, by almost equal amounts.

The report studies rural-urban migration as well, principally through the recent Chinese experience, which has been called the greatest mass migration in history. That migration shows some of the same convergence characteristics of the international experience, with the happiness of city-bound migrants moving towards, but still falling below urban averages.

The importance of social factors in the happiness of all populations, whether migrant or not, is emphasized in Chapter 6, where the happiness bulge in Latin America is found to depend on the greater warmth of family and other social relationships there, and to the greater importance that people there attach to these relationships.

The Report ends on a different tack, with a focus on three emerging health problems that threaten happiness: obesity, the opioid crisis, and depression. Although set in a global context, most of the evidence and discussion are focused on the United States, where the prevalence of all three problems has been growing faster and further than in most other countries.

Appendices & Data

Editors

John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey D. Sachs

WHR 2021 | Chapter 1 Overview: Life under COVID-19

2020 has been a year like no other. This whole report focuses on the effects of COVID-19 and how people all over the world have fared. Our aim was two-fold, first to focus on the effects of COVID-19 on the structure and quality of people’s lives, and second to describe and evaluate how governments all over the world have dealt with the pandemic. In particular, we try to explain why some countries have done so much better than others.

Happiness, trust, and deaths under COVID-19 (Chapter 2)

There has been surprising resilience in how people rate their lives overall. The Gallup World Poll data are confirmed for Europe by the separate Eurobarometer surveys and several national surveys.

COVID-19 Prevalence and Well-being: Lessons from East Asia (Chapter 3)

East Asia, Australia, and New Zealand’s success are explained in detail as a case study in Chapter 3. The chapter describes country by country, the workings of test and trace and isolate, and travel bans to ensure that the virus never got out of control. It also analyses citizens’ responses, stressing that policy can be effective when citizens are compliant (as in East Asia) and more freedom-oriented (as in Australia and New Zealand). In East Asia, as elsewhere, the evidence shows that people’s morale improves when the government acts.

Reasons for Asia-Pacific Success in Suppressing COVID-19 (Chapter 4)

Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic (Chapter 5)

Mental health has been one of the casualties both of the pandemic and the resulting lockdowns. As the pandemic struck, there was a large and immediate decline in mental health in many countries worldwide. Estimates vary depending on the measure used and the country in question, but the findings are remarkably similar. In the UK, in May 2020, a general measure of mental health was 7.7% lower than predicted in the absence of the pandemic, and the number of mental health problems reported was 47% higher.

Social Connections and Well-being during COVID-19 (Chapter 6)

Work and Well-being During COVID-19: Impact, Inequalities, Resilience, and the Future of Work (Chapter 7)

Living long and living well: the WELLBY approach (Chapter 8)

To evaluate social progress and to make effective policy, we have to take into account both:

Health economists use the concept of Quality-Adjusted Life Years to do this, but they only count the individual patient’s health-related quality of life. In the well-being approach, we consider total well-being, whoever experiences it, and for whatever reason: All policy-makers should aim to maximise the Well-Being-Adjusted Life-Years (or WELLBYs) of all who are born. And include the life-experiences of future generations (subject to a small discount rate).

The World Happiness Report is a publication of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, powered by the Gallup World Poll data.

The Report is supported by The Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s, The Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff, and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, The Happier Way Foundation, and The Regenerative Society Foundation.

The World Happiness Report was written by a group of independent experts acting in their personal capacities. Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization, agency or program of the United Nations.

World happiness report

This is the 10th anniversary of the World Happiness Report, written as the world is entering the third year of COVID-19. As a result, the Report has a triple focus, first looking back, then taking another close look at how individuals and countries are doing in the face of COVID-19, and finally looking ahead to how the science of well-being, and the societies under study, are likely to evolve in the future.

Looking back involves studying the trends of happiness over the first 15 years of data from the Gallup World Poll (in Chapter 2) and examining how interest in happiness measures and policies has evolved before and since the first World Happiness Report published in 2012 (in Chapter 3).

The analysis of how life has changed for people during the first two years of COVID-19 is in Chapter 2 and, for a selection of countries, using large samples of Twitter data (in Chapter 4). A striking feature of the 2021 data is the globe-spanning upsurge in three types of benevolent activity: helping strangers, volunteering, and donations.

The final three chapters look ahead to consider some new types of evidence and analysis that are likely to contribute to future understanding of happiness. These include the use of big data (in Chapter 4), a deeper understanding of the biological correlates of happiness (in Chapter 5), and some illustrative findings from using measures of balance and peace to broaden the empirical base (in Chapter 6).

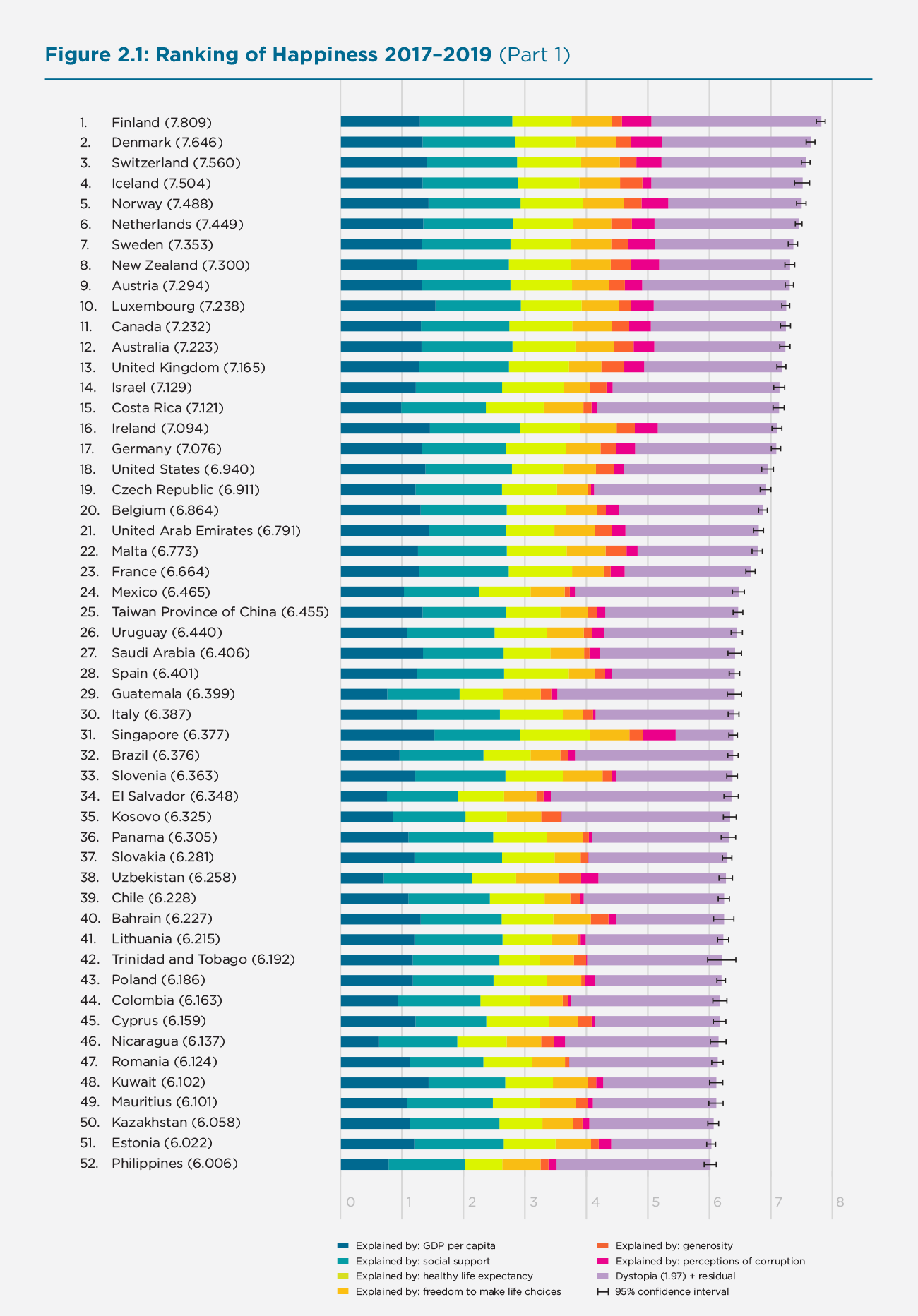

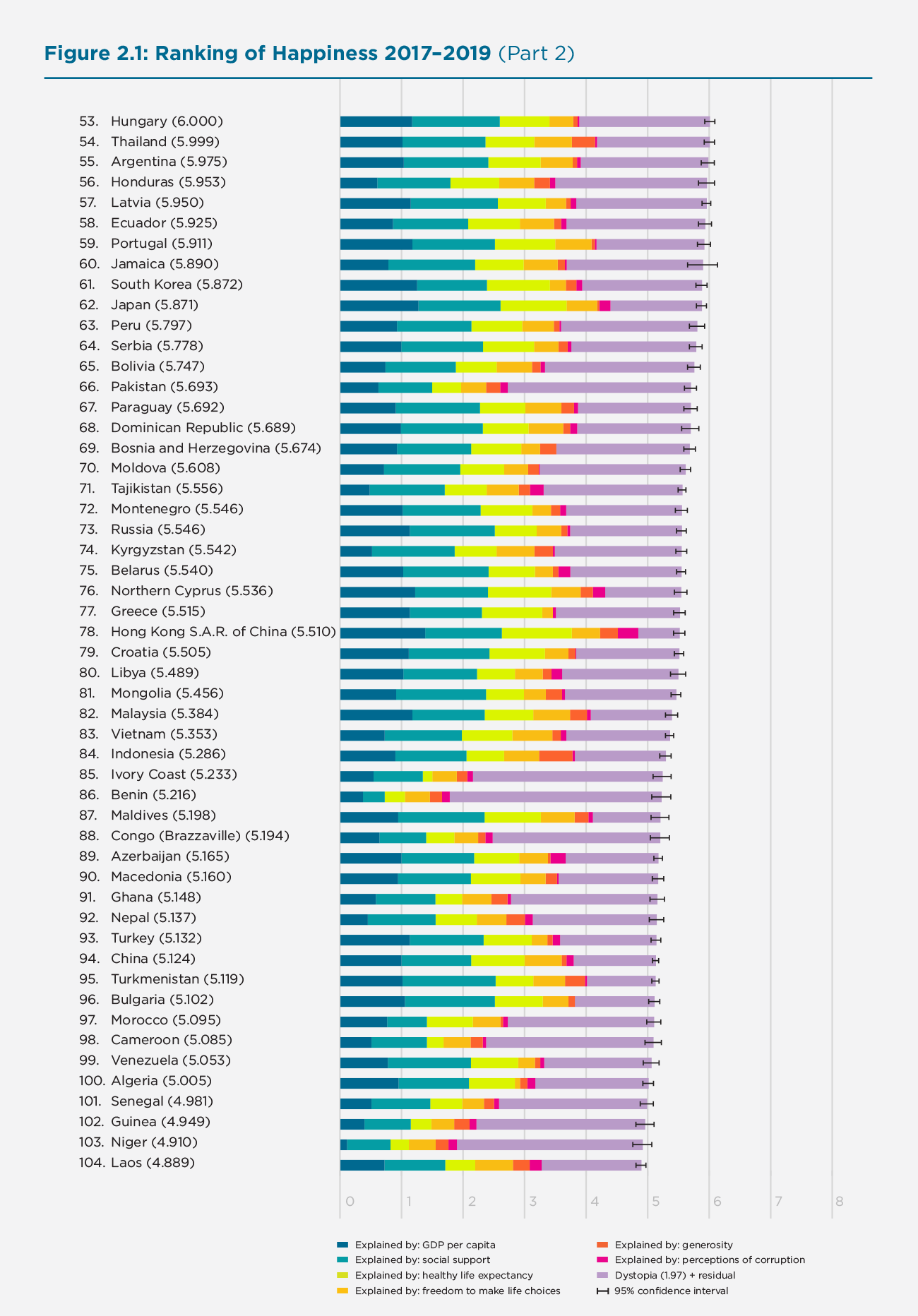

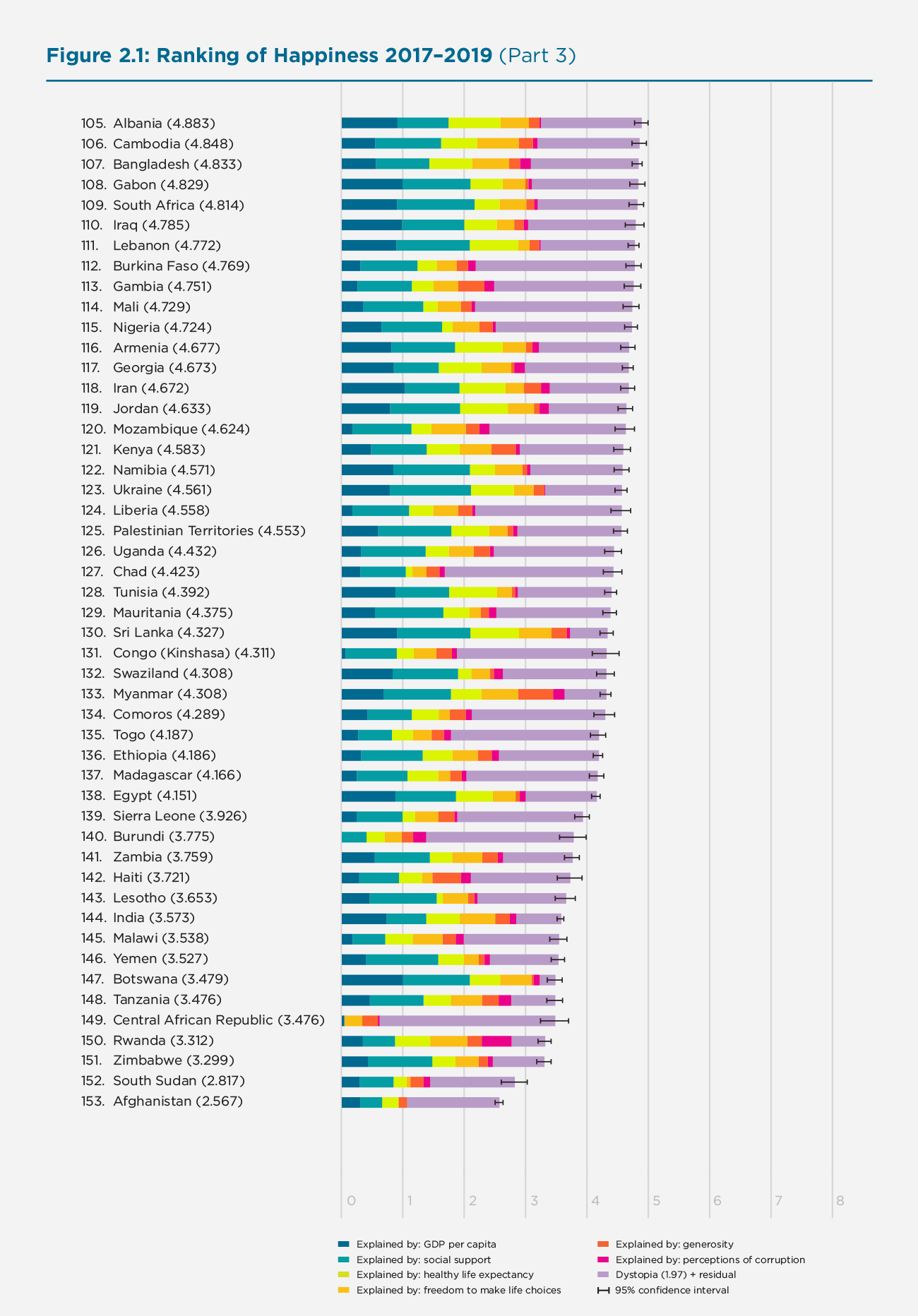

What is the original source of the data for Figure 2.1? How are the rankings calculated?

What is your sample size for Figure 2.1?

The typical annual sample for each country is 1,000 people. However, many countries have not had annual surveys. If a typical country had surveys each year, the sample size would be 3,000. We use responses from the three most recent years to provide an up-to-date and robust estimate of life evaluations. In this year’s report, we combine data from 2019-2021 to make the sample size large enough to reduce the random sampling errors. Tables 1-5 of the online Statistical Appendix 1 show the sample size for each country.

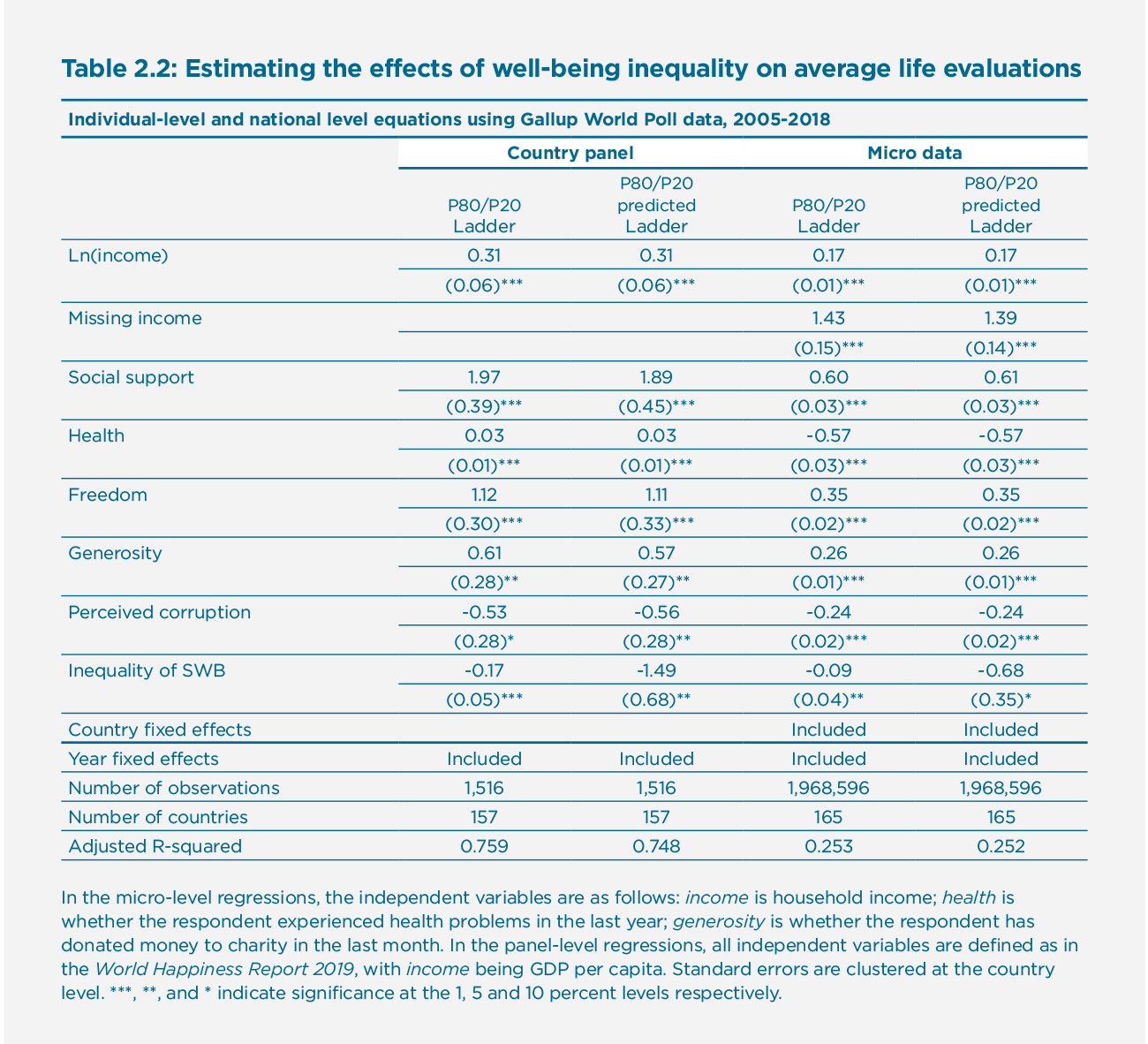

Our interest in exploring how COVID-19 influenced happiness for people in different countries and circumstances, we have done much of our analysis using individual-level data (as reported in Tables 2.2, 2.3, and 2.4).

Is this sample size really big enough to calculate rankings?

A sample size of 2,000 to 3,000 is large enough to give a reasonably good estimate at the national level. This is confirmed by the 95% confidence intervals shown at the right-hand end of each country bar.

What is a data “wave”?

Gallup refers to the surveys collected in each calendar year as part of that year’s survey wave. Waves correspond to calendar years in an overwhelming majority of cases, but there are a few exceptions. Some surveys completed in early 2022 are considered part of the 2021 wave. Not every country is surveyed every year. Thus, the size of the survey waves also varies from year to year.

What is the confidence interval?

As shown by the horizontal lines (or light grey highlight) at the right-hand end of the country bars, the confidence intervals show the range of values within which there is a 95% likelihood of the population mean being located. These are useful for readers wishing to see whether countries differ significantly in the average life evaluations; countries with non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals are estimated to have statistically different average life evaluation ratings.

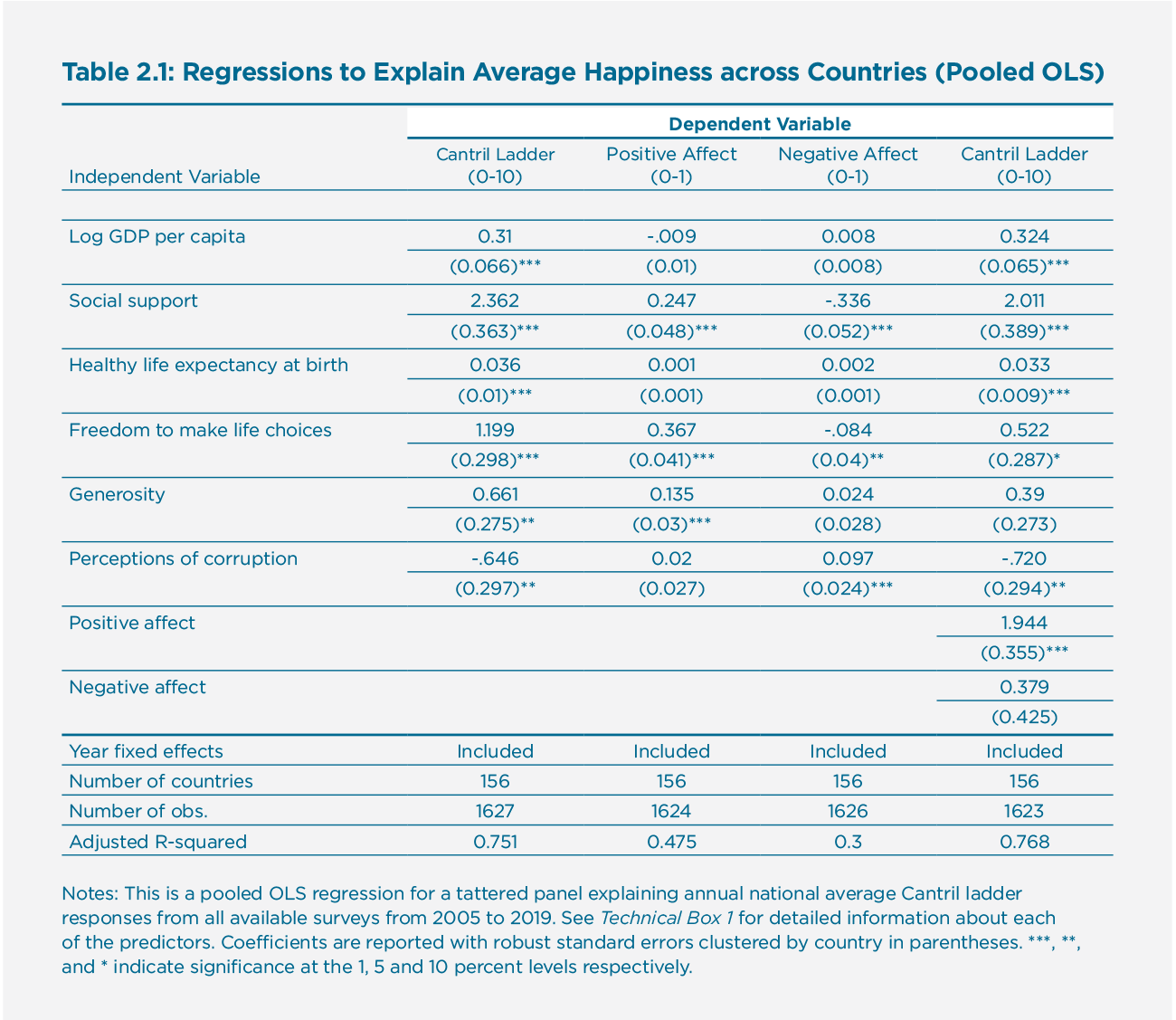

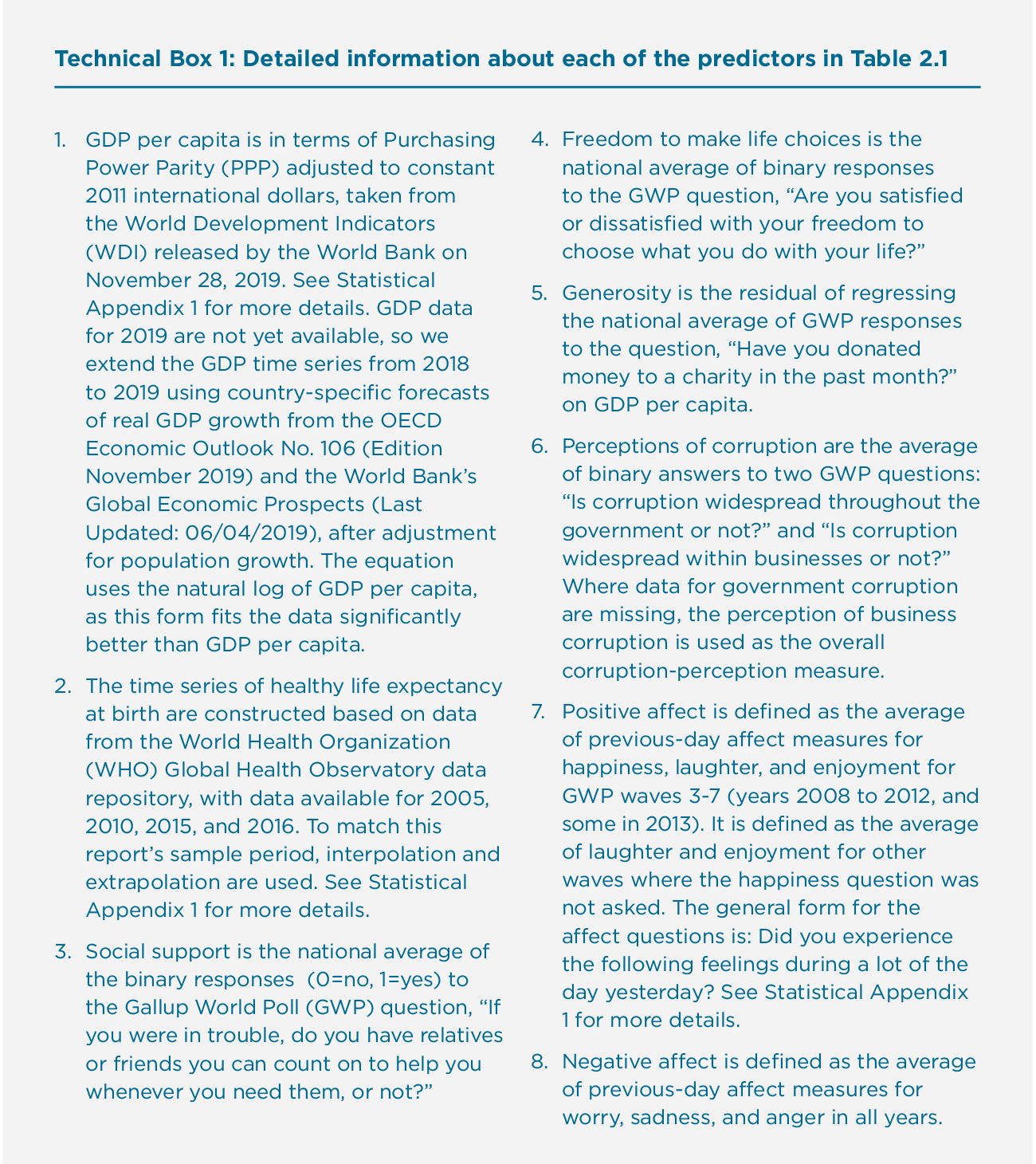

Where do the sub-bars come from for each of the six explanatory factors?

The sub-bars show, tentatively, what share of a country’s overall score can be explained by each of the six factors in Table 2.1. The sub-bars are calculated by multiplying average national data for the period of 2019-2021 for each of the six factors (minus the value of that variable in Dystopia) by the coefficient on this variable in the first equation of Table 2.1. This product then shows the average amount by which the overall happiness score (the life evaluation) is higher in a country because they perform better than Dystopia on that variable. More on this under the question relating directly to Dystopia.

To describe an example, let’s look at the variable of life expectancy in the case of Brazil. First, we calculate the number of years by which healthy life expectancy in Brazil exceeds that of the country with the lowest life expectancy. Then, we multiply this number of years by the estimated coefficient for life expectancy in the first column of Table 2.1. This product then shows the average amount by which the overall happiness score (the life evaluation) is higher in Brazil because life expectancy is higher than in the country with the lowest life expectancy. This process is repeated for each country and for each of the six variables.

Because of how these six bars were constructed, they will always total to less than each country’s average life evaluation. They will not alter in any way the width of the overall life evaluation bar on which the rankings are based. The difference between what is attributed to the six factors and the total life evaluations is the sum of two parts. These are the average life evaluations in Dystopia and each country’s residual. You may find the following FAQs useful: What is Dystopia? What are the residuals?

What is Dystopia?

Dystopia is an imaginary country that has the world’s least-happy people. The purpose in establishing Dystopia is to have a benchmark against which all countries can be favorably compared (no country performs more poorly than Dystopia) in terms of each of the six key variables, thus allowing each sub-bar to be of positive (or zero, in six instances) width. The lowest scores observed for the six key variables, therefore, characterize Dystopia. Since life would be very unpleasant in a country with the world’s lowest incomes, lowest life expectancy, lowest generosity, most corruption, least freedom, and least social support, it is referred to as “Dystopia,” in contrast to Utopia.

What are the residuals?

The residuals, or unexplained components, differ for each country, reflecting the extent to which the six variables either over- or under-explain average 2019-2021 life evaluations. These residuals have an average value of approximately zero over the whole set of countries.

Why do we use these six factors to explain life evaluations?

The variables used reflect what has been broadly found in the research literature to explain national-level differences in life evaluations. Some important variables, such as unemployment or inequality, do not appear because comparable international data are not yet available for the full sample of countries. The variables are intended to illustrate important lines of correlation rather than to reflect clean causal estimates since some of the data are drawn from the same survey sources. Some are correlated with each other (or with other important factors for which we do not have measures). There are likely two-way relations between life evaluations and the chosen variables in several instances. For example, healthy people are overall happier, but as Chapter 4 in World Happiness Report 2013 demonstrated, happy people, are overall healthier. Statistical Appendix 1 of World Happiness Report 2018 assessed the possible importance of using explanatory data from the same people whose life evaluations are being explained. We did this by randomly dividing the samples into two groups and using the average values for, e.g., freedom gleaned from one group to explain the life evaluations of the other group. This lowered the effects, but only very slightly (e.g., 2% to 3%), assuring us that using data from the same individuals is not seriously affecting the results.

Social media are now even more important for people around the globe. How do they influence happiness?

There was a special chapter on social media in World Happiness Report 2019, emphasizing the damaging effects of social media use on the happiness and self-image of adolescents, mainly based on data from the United States. This runs parallel to evidence from earlier Reports showing that in-person friendships support happiness, while online connections do not. But COVID-19 and its limitations on in-person meetings offered a chance for electronic connections to develop their potential for creating and maintaining the social bonds that support happiness. Social media have, in consequence, become much more social in the uses to which they have been put, as virtual hugs have been used to fill in for the real thing.

Can I download any of the data used in the Report?

Yes. The online data appendices show how the data are constructed and include the main national and regional averages underlying the figures and tables in Chapter 2. Those wishing access to more detailed data from the Gallup World Poll should contact Gallup directly.

Why is Bhutan not listed in the 2022 WHR?

During the pandemic, Bhutan once again provided an inspiring example for the world about how to combine health and happiness. They made explicit use of the principles of Gross National Happiness in mobilizing the whole population in collaborative efforts to avoid even a single COVID-19 death in 2020, despite having strong international travel links. Although it has not been possible to have Bhutan in the rankings this year, because Gallup did not survey the country in recent years, they continue to inspire the world, particularly the World Happiness Report. There was a special chapter on Bhutan in the first World Happiness Report.

The World Happiness Report is a publication of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, powered by the Gallup World Poll data.

The Report is supported by The Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s, The Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff, and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, The Happier Way Foundation, and The Regenerative Society Foundation.

The World Happiness Report was written by a group of independent experts acting in their personal capacities. Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization, agency or program of the United Nations.

WHR 2020 | Chapter 1 Environments for Happiness: An Overview

This year the World Happiness Report focuses especially on the environment – social, urban, and natural.

After presenting our usual country rankings and explanations of life evaluations in Chapter 2, we turn to these three categories of environment, and how they affect happiness.

The social environment is dealt with in detail in the later parts of Chapter 2. It is also a main focus of Chapter 7, which looks at happiness in the Nordic countries and finds that higher personal and institutional trust are key factors in explaining why life evaluations are so high in those countries.

Urban life is the focus of Chapter 3, which examines the happiness ranking of cities, and of Chapter 4, which compares happiness in cities and rural areas across the world. An Annex considers recent international efforts to develop common definitions of urban, peri-urban, and rural communities.

The natural environment is the focus of Chapter 5, which examines how the local environment affects happiness. Chapter 6 takes a longer and broader focus on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The wide range of the SDGs links them to all three of the environmental themes considered in other chapters.

In the rest of this Overview chapter, we synthesize the main findings relating to the three environmental themes. We then conclude with a brief summary of the individual chapters whose results are being reviewed here.

Social Environments for Happiness

In the first half of Chapter 2, six factors are used to explain happiness, and four of these measure different aspects of the social environment: having someone to count on, having a sense of freedom to make key life decisions, generosity, and trust. The second half of the chapter digs deeper, paying special attention first to the effects that inequality has on average happiness, and then on how a good social environment operates to reduce inequality. Just as life evaluations provide a broader measure of well-being than income does, inequality of well-being turns out to be more important than income inequality in explaining average levels of happiness. Well-being inequality significantly reduces average life evaluations, suggesting that people are happier to live in societies with less disparity in the quality of life.

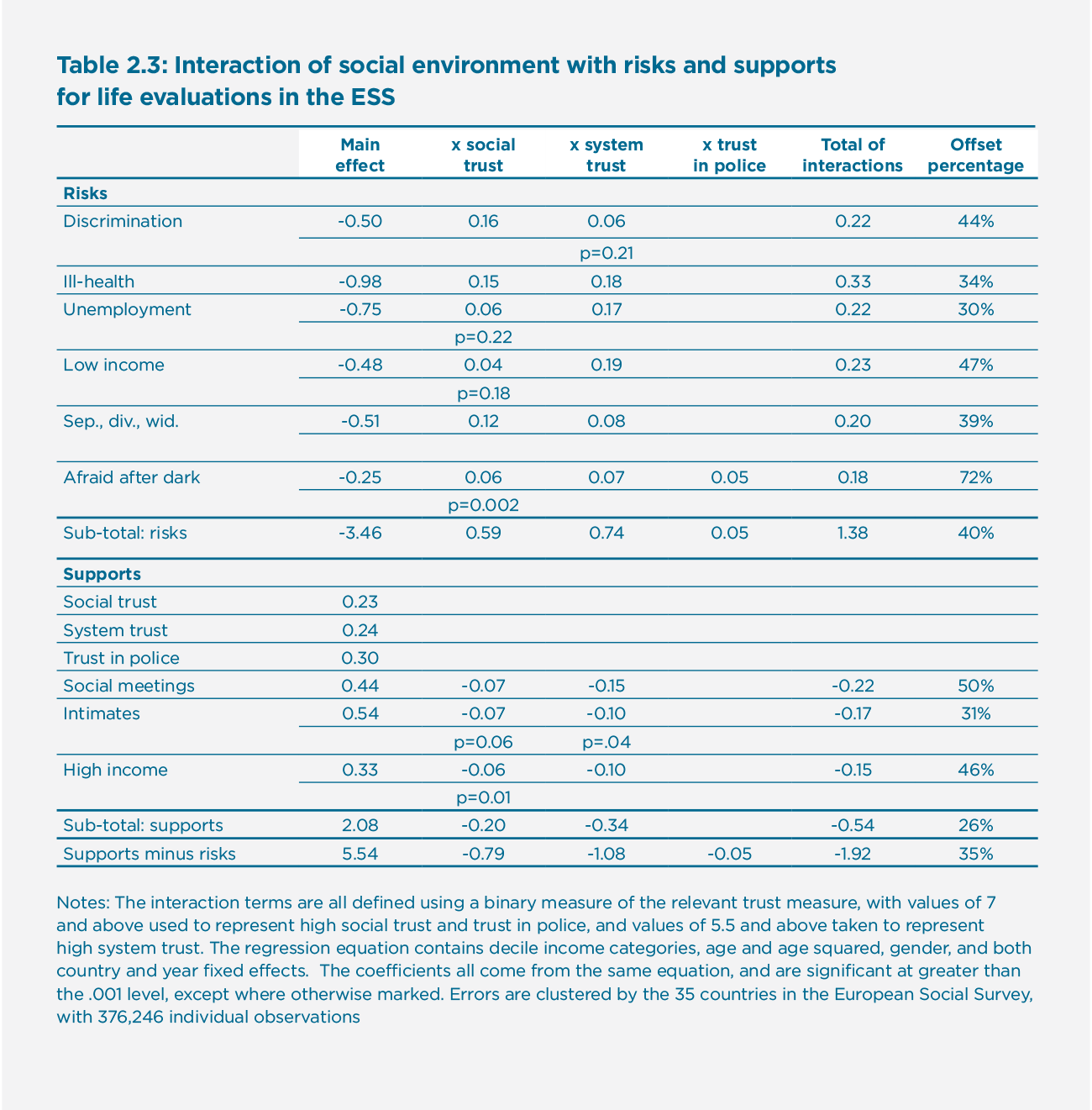

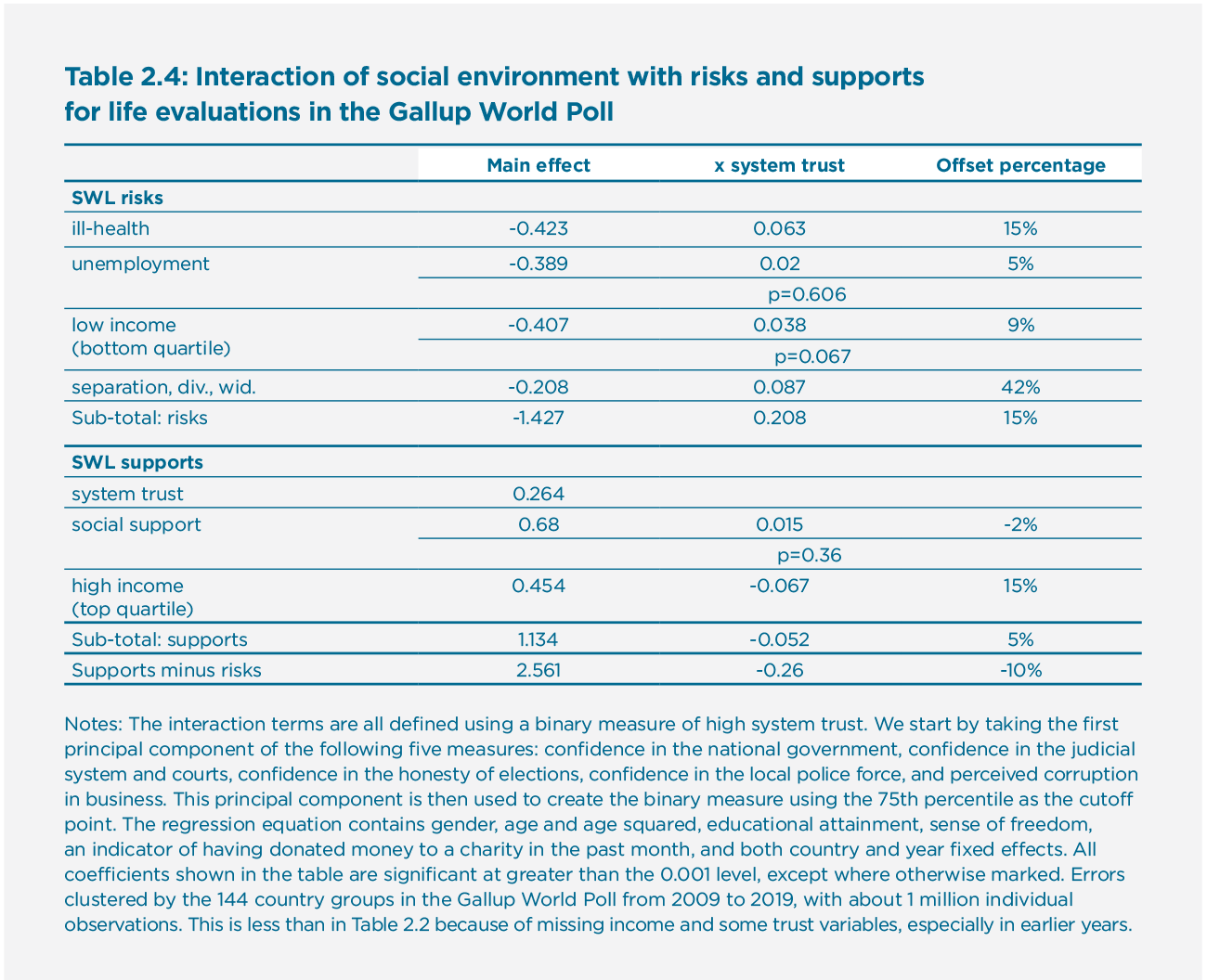

The next step is to explore what determines well-being inequality, and to see how the effects of misfortune on happiness are moderated by the strength and warmth of the social fabric. Life evaluations are first explained at the individual level based on income, health, and a variety of measures of the quality of the social environment. Several particular risks are considered: ill-health, discrimination, low income, unemployment, separation, divorce or widowhood, and safety in the streets. The happiness costs of these risks are very large, especially for someone living in a low-trust social environment. For example, Marie, who is in good health, employed, married, with average income, sees herself as free from discrimination, and feels safe in the streets at night is estimated to have life satisfaction 3.5 points higher, on the 0 to 10 scale, than Helmut, who is in fair or worse health, unemployed, in the bottom-fifth of the income distribution, divorced, and afraid in the streets at night. This is the difference if they both live in a relatively low-trust environment. But if they both lived where trust in other people, government, and the police were relatively high, the well-being gap between them would shrink by one-third. The well-being costs of hardship are thus significantly less where there is a positive social environment within which one is more likely to find a helping hand and a friendly face. Since hardships are more prevalent among those at the bottom of the well-being ladder, a trusting social environment does most to raise the happiness of those in distress, and hence delivers greater equality of well-being.

A similar story emerges when we look at supports for well-being, which include the direct effects of social and institutional trust, high incomes, close social support and frequent meetings with friends. Let’s consider the example of Luigi, who is in the top-third of Europeans in terms of the trust he has in other people, government, and the police, meets socially with friends weekly or more, has at least one person with whom to discuss intimate problems, and is in the top fifth of the distribution of household income. He has a happiness level 1.8 points higher than Klara, who lives in a low trust environment with weak social ties. This gap is reduced by one-fifth when we take account of the fact that the advantages of higher income and close personal social supports are less significant in an environment of generally high social trust.

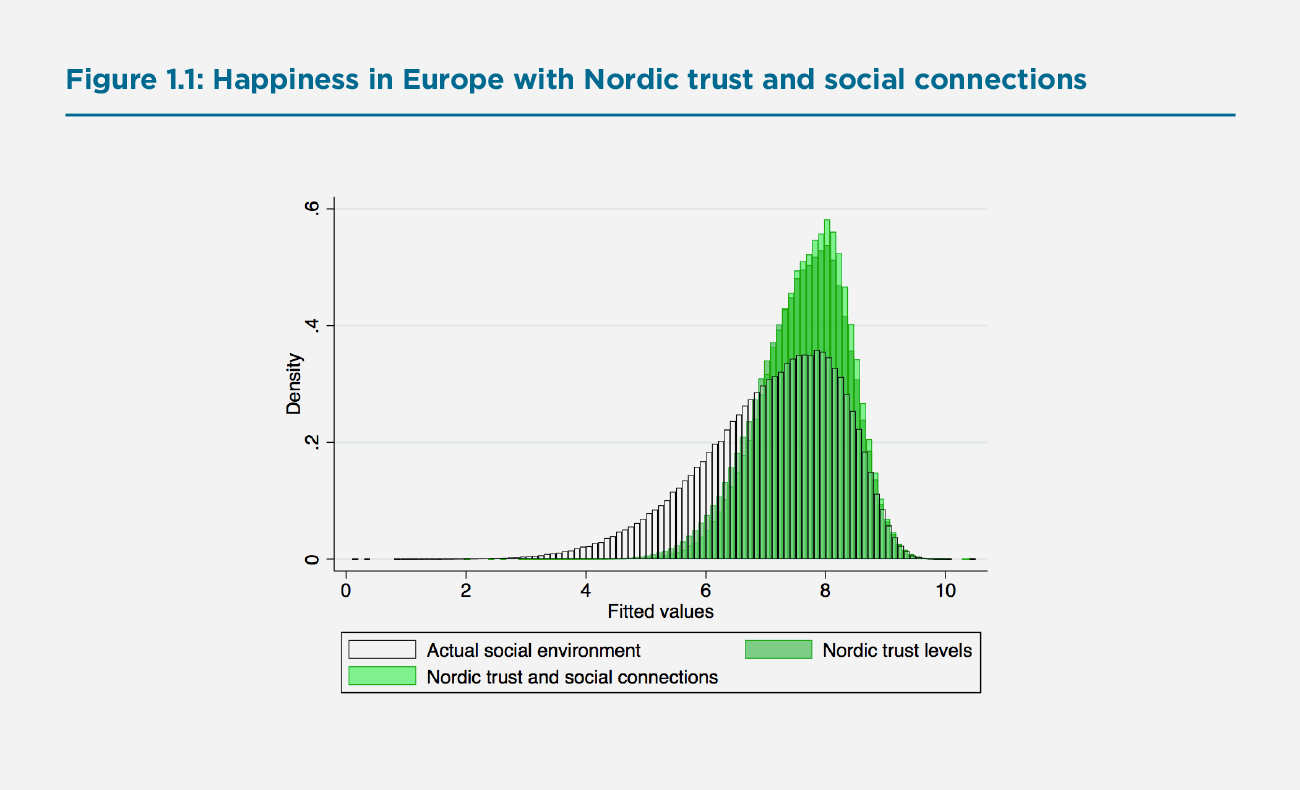

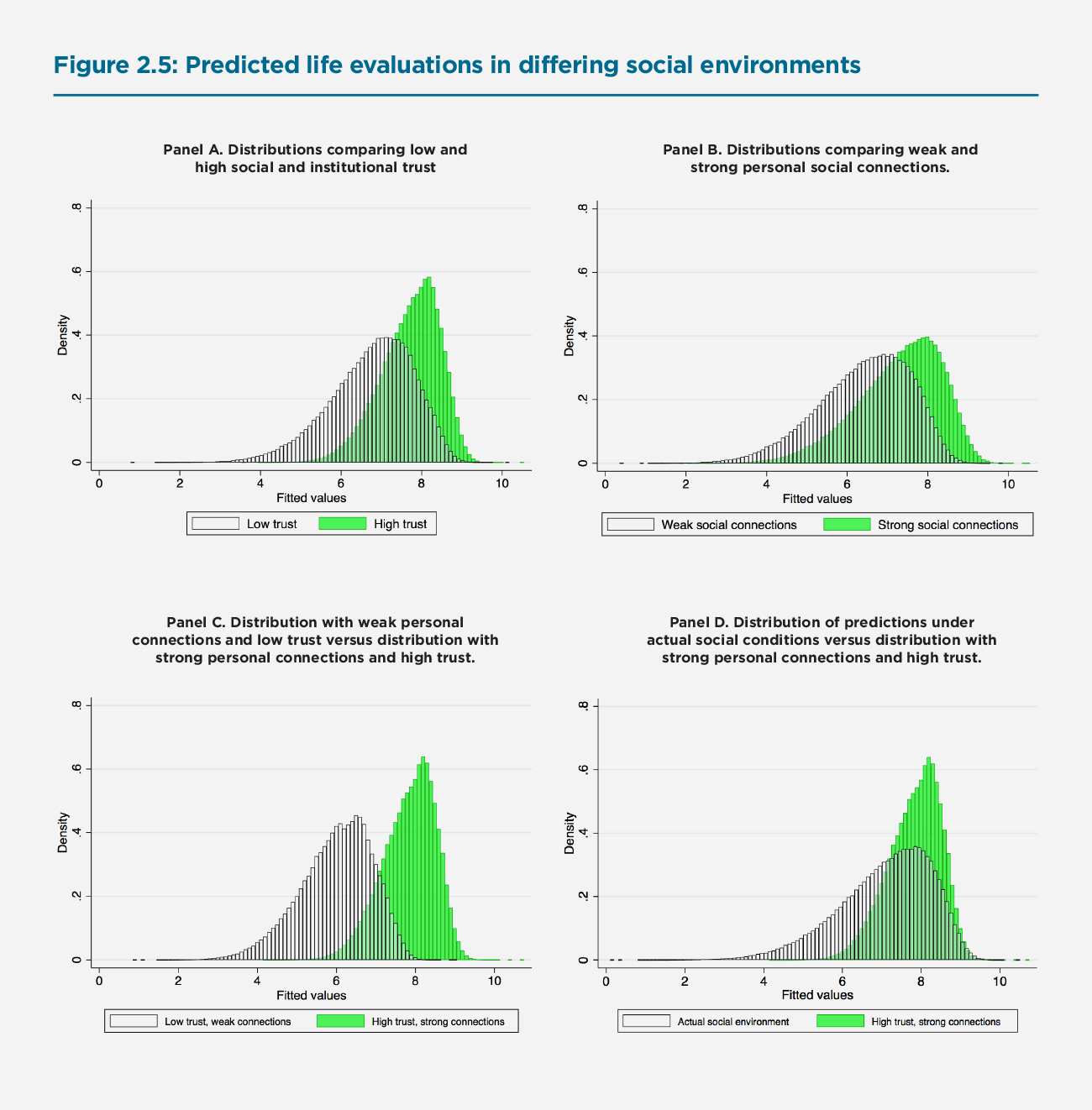

This new evidence of the power of an environment to raise average life quality and to reduce inequality can be used to illustrate the analysis of Chapter 7, which explains the higher happiness of the Nordic countries largely in terms of the high quality, often hard-won, of their local and national social environments. We can illustrate this by comparing the distribution of happiness among 375,000 individual Europeans in 35 countries with what it would be if all countries had the same average levels of social trust, trust in institutions, and social connections as are found in the Nordic countries. The new distribution does not change anyone’s health, income, employment, family status, or neighbourhood safety, all of which are more favourable, on average, in the Nordic countries than in the rest of Europe. In Figure 1.1 we simply increase each person’s levels of trust and social connections to the average of those living in the Nordic countries, to give some idea of the power of a good social environment to raise the average level and lower the inequality of well-being.

Figure 1.1: Happiness in Europe with Nordic trust and social connections

The results shown in Figure 1.1 are striking. The current European distribution of happiness (shown in black and white, with a mean value of 7.09) shifts significantly, with a higher mean and with much less inequality if the trust and social connection levels of the Nordic countries existed across all of Europe (as shown in two-tone green, with a mean value of 7.68). The darker green bars show the effects of the trust increases on their own, while the lighter green bars show what is added by having Nordic levels of social connections. The trust increases alone are sufficient to raise average life evaluations by 0.50 points (to 7.59), thereby accounting for more than half the amount by which actual life satisfaction in the Nordic countries (=8.05) exceeds than of Europe as a whole. The Nordic social connections add another 0.09 points. Together the changes in trust and social connections explain 60% of the happiness gap between the Nordic countries and Europe as a whole. Although close social connections are very important, they are only modestly more prevalent in the Nordic countries than elsewhere in Europe. It is the higher levels of social and institutional trust that are especially important in raising happiness and reducing inequality.

Urban Happiness

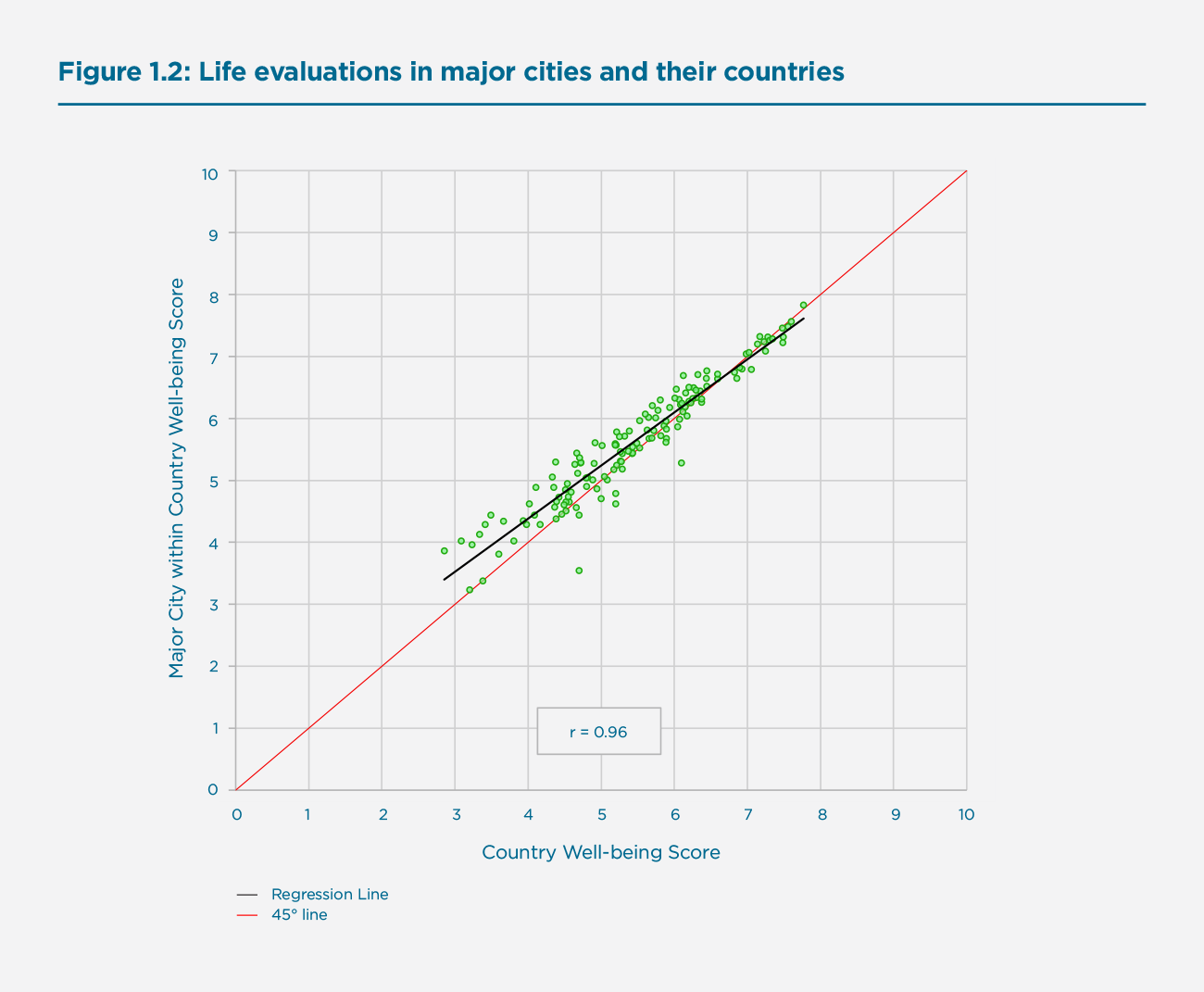

This Report marks the first time that we have looked at the happiness of city life across the world, both comparing cities with other cities and looking at how happy city dwellers are, on average, compared to others living in the same country. The results are contained in the city rankings of Chapter 3, the urban/rural happiness comparisons of Chapter 4, and an Annex presenting and making use of new urban definitions from the EU and other international partners. There are several striking findings in the two chapters, as illustrated by Figure 1.2. The figure plots the average life evaluations of city dwellers in 138 countries against average life evaluations in the country as a whole, in both cases measured using all available Gallup World Poll responses for 2014-2018.

Figure 1.2: Life evaluations in major cities and their countriesons

Three key facts are immediately apparent from Figure 1.2, all of which are amplified and explained in the chapters on urban life. First, city rankings and country rankings are essentially identical. Second, in most countries, especially at lower levels of average national happiness, city dwellers are happier than those living outside cities by about 0.2 points on the life evaluation scale running from 0 to 10. Third, the urban happiness advantage is less and sometimes negative in countries at the top of the happiness distribution. This is shown by the regression line in Figure 1.2.

If the ranking of city-level life evaluations mimics that of the countries in which they are located, then we would expect cities from the same country to be clustered together in the city rankings. This is indeed what we find. For example, the 10 large US cities included in the cities ranking all fall between positions 18 and 31 in the list of 186 cities. The fact that two Swedish cities, Stockholm and Göteborg, differ by fifteen places in the rankings, 9 for Stockholm and 24 for Göteborg, might suggest a large gap between two cities in the same country. But they lie within the same statistical confidence region, partly because of the number of similarly scoring US cities lying between Göteborg and Stockholm in the rankings, and partly because of the small samples available for cities outside the United States.

The urban/rural chapter pays special attention to the declining urban advantage as development proceeds and lists a number of contributing factors. Their key Figure 4.3 actually shows average urban happiness falling below average rural happiness after some level of economic development. In most regions of the world, the higher levels of happiness in cities can be explained by better economic circumstances and opportunities in cities. Although in a number of the richer countries the rural population is happier than its urban counterpart, cities that combine higher income with high levels of trust and connectedness are less likely to have their life evaluations fall below the national average as they become richer. In the relatively few countries with detailed data on life satisfaction of communities of all sizes, and where rural communities are happier than major urban centres, the key factor correlated with the rural advantage in average life evaluations is the extent to which people feel a sense of belonging to their local community. Another factor is inequality of happiness, which is more prevalent in urban communities. For example, in Canada, life evaluations are 0.18 points higher in rural neighbourhoods than in urban ones. [1] This gap is halved if community belonging is maintained, or reduced to one-third if well-being inequality is also maintained at the levels of the rural communities. [2] Thus the social environments discussed above seem also to be important in explaining differences in happiness between urban and rural communities.

Sustainable Natural Environments

The natural environment is the focus of both Chapters 5 and 6. Chapter 5 starts by noting the widespread surge in interest in protecting the natural environment, supported by Gallup World Poll data showing widespread public concern about the environment. The chapter then presents two sorts of evidence, the first international and the second local and immediate. For the first, the chapter assesses how national average densities of various pollutants and different aspects of the climate and land cover affect average life evaluations in those OECD countries where data on these measures are recorded. Treating a number of pollutants separately, the authors find significant negative effects on life evaluations from several air-borne pollutants (shown in Figure 5.2a and 5.2b), with fairly similar effects on positive affect, but none on negative affect. Forests have significant positive effects on life evaluations, but none on emotions. The chapter also shows some small but significant preference for more moderate temperatures, especially in rural areas.

The second strand of the evidence shifts from national data to very local experiences of a sample of 13,000 volunteers in greater London whose phones reported their locations when they were asked on half a million occasions to report their emotional states, what they were doing, and with whom they were doing it. These answers were than collated with detailed environmental data for the time and location of each response. These data included closeness to rivers, lakes, canals and greenspaces, air quality and noise levels, and weather conditions. The activities included work, walking, sports, gardening, and birdwatching, in all cases in comparison with being sedentary at home. Nearby public parks and trees in the streets, as well as closeness to the River Thames or a canal, spurred positive moods. Mood appeared unaffected by local concentrations of particulate matter PM10, while NO2 concentrations had a modest negative impact only in certain model specifications. Weather had an effect on emotional state, with better moods in sunshine, clear skies, light winds, and warm temperatures. Moods were better outdoors than indoors, and worse at work. As for other activities, many were accompanied by significant changes in moods. Moods rather than life evaluations are used for these very short-term reports, since life evaluations tend to be stable under such temporary changes, although, as shown in Chapter 2, accumulated positive moods contribute to higher life evaluations.

Supplementary material in the on-line appendix to Chapter 5 links activities directly to the social environment, using a large sample of 2.3 million responses in the United Kingdom. All of the 43 listed activities improve moods when done with a friend or partner. For example, to hike or walk alone raises mood by 2%, while a shared walk raises mood by much more, by 7.5% with a friend or 8.9% with a partner. Activities that normally worsen moods can induce happiness when done in the company of a friend or partner. Commuting or traveling, activities that on average worsen mood levels (-1.9%) are happiness-inducing when shared with friends or partners, with mood up 5.3% for a trip shared with a friend, or 3.9% with a partner. Even waiting or queueing, a significant negative when done alone (-3.5%) becomes a net positive when the experience is done with the company of a friend (+3.5%). These estimated effects may be exaggerated when friends are normally not invited along for unpleasant queues or trips. But they may be underestimated for those who want a friend or partner along to help them deal with waits for bad news at the doctor’s office or long queues at the airport. Even taken with a grain of salt, these are large effects. These snapshots from the daily lives of UK residents confirm what much other research has shown, namely that experiences make people happier when they are shared with others.

Chapter 6 moves from the more immediate natural environment to the broader long-term environment, mainly by testing the linkages between the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and people’s current life evaluations. The chapter makes the general case for using life evaluations as a way of providing an umbrella measure of well-being likely to be improved by achieving progress towards the SDG targets. The goals themselves came from quite diverse attempts to set measurable standards for natural environmental quality and the quality of life, but there is a strong case for some overarching measure to help evaluate the importance of each separate SDG.

The primary empirical finding of Chapter 6 is that international differences in reaching the SDGs are positively and strongly correlated with international differences in life evaluations, with goal attainment rising even faster among the happiest countries, which implies increasing marginal returns to sustainable development in terms of happiness. However, unpacking the SDGs by looking at how each SDG relates to life evaluations—as well as how these relationships play out by region—reveals much heterogeneity. For example, SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) and SDG 13 (climate action) are negatively correlated with life evaluations, a finding which holds for SDG 12 even when controlling for general level of economic development. These insights suggest that more complex and contextualized policy efforts are needed to chart a course towards environmentally sustainable growth that also delivers high levels of human well-being.

Generally, what might make achievement of the SDGs so closely match overall life evaluations? Part of the reason, of course, is that many of the specific goals cover the same elements, e.g. good health and good governance, that have been pillars in almost all attempts to understand what makes some nations happier than others. However, there is a deeper set of reasons that may help to explain why actions to achieve long-term sustainability are more prevalent among the happier countries. As shown in Chapter 7 on Nordic happiness, and earlier in this synthesis, people are happier when they trust each other and their shared institutions, and care about the welfare of others. Such caring attitudes are then typically extended to cover those elsewhere in the world and in future generations. This trust also increases social and political support for actions to help secure the futures of those in other countries and future generations. Thus, actions required to achieve the longer-term sustainable development goals are more likely to be met in those countries that have higher levels of social and institutional trust. But these are the countries that already rank highest in the overall rankings of life evaluations, so it is not surprising that actual attainment of SDG targets, and political support for those objectives, is especially high in the happiest countries, as is shown in Chapter 6. The same social connections that favour current happiness are also likely to support actions to improve the quality and security of the environment for future generations.

To re-cap, the structure of the chapters to follow is:

References

Helliwell, J. F., Shiplett, H., & Barrington-Leigh, C. P. (2019). How happy are your neighbours? Variation in life satisfaction among 1200 Canadian neighbourhoods and communities. PloS one, 14(1).

Endnotes

When roughly 400,000 life satisfaction observations, on the 0 to 10 scale, from several years of Canadian Community Health Surveys were divided among 1200 contiguous communities spanning the whole of Canada, they showed average life satisfaction in the roughly 800 urban communities to be 0.18 points lower (p Back to the 2020 report

The World Happiness Report is a publication of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, powered by the Gallup World Poll data.

The Report is supported by The Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s, The Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff, and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, The Happier Way Foundation, and The Regenerative Society Foundation.

The World Happiness Report was written by a group of independent experts acting in their personal capacities. Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization, agency or program of the United Nations.

Report 2020

WORLD HAPPINESS REPORT

The World Happiness Report ranks countries by their happiness levels.

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the report, which uses global survey data to report on how people evaluate their own lives in more than 150 countries around the world.

In this troubled time of war and pandemic, the World Happiness Report 2022 reports a bright light in dark times. The pandemic brought not only pain and suffering but also an increase in social support and benevolence.

Headlines FRom 2022

* Finland tops the happiness rankings for the fifth year in a row

* Denmark, Iceland, Switzerland & Netherlands complete the top 5

* Countries suffering from conflict and extreme poverty score lowest

* This year’s report highlights how benevolence and trust have contributed to well-being during the pandemic.

Helping strangers, volunteering, and donations were strongly up in every part of the world, reaching levels almost 25% above their pre-pandemic prevalence

The good news is kind behaviours rose significantly during the pandemic. Acts of kindness and generosity can help us cope in difficult times by giving us a sense of purpose, something practical to focus on and showing the strength of the human spirit. We can build good mental health by taking positive action to help others

Since the World Happiness Report was launched, there has been a growing interest in measuring well-being and life satisfaction.

Looking back over fifteen years of data covering more than 150 countries, the three countries with the biggest gains in happiness were in Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania. The biggest losses were in Lebanon, Venezuela, and Afghanistan.

The lesson of the World Happiness Report is that social support, generosity to one another, and honesty in government are crucial for well-being. World leaders should take heed. Politics should be directed to the well-being of the people, not the power of the rulers

The World Happiness Report is a publication of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, powered by the Gallup World Poll data.

The Report is supported by The Ernesto Illy Foundation, illycaffè, Davines Group, Unilever’s largest ice cream brand Wall’s, The Blue Chip Foundation, The William, Jeff, and Jennifer Gross Family Foundation, The Happier Way Foundation, and The Regenerative Society Foundation.

WHR 2022 | Chapter 6 Insights from the First Global Survey of Balance and Harmony

Introduction

Scholarly understanding of happiness continues to advance with every passing year, with new ideas and insights constantly emerging. Some constructs, like life evaluation, have been established for decades, generating extensive research. Cantril’s “ladder” item on life evaluation, for example — the question in the Gallup World Poll upon which this report is based — was created in 1965. [1] By contrast, other well-being related topics are only beginning to receive due recognition and attention, including balance and harmony.

Balance and harmony — concepts that are closely linked but not synonymous — are used and defined in myriad ways, each having “fuzzy” [2] conceptual boundaries. We shall delve into their meaning in the first subsection below, but we can note here that across academic fields, they are invoked as important principles in the context of phenomena as varied as emotions, [3] attention, [4] motivation, [5] character, [6] diet, [7] sleep, [8] exercise, [9] work-life patterns, [10] relationships, [11] society, [12] politics, [13] and nature. [14] Furthermore, in the present day, balance/harmony are particularly associated with Eastern cultures. [15] But does that mean they have been overlooked or undervalued in the rest of the world? Possibly not. There are significant ideas and traditions around balance/harmony in the West, such as Aristotle’s ideal of the “golden mean.” [16]

In addition, two key well-being related domains in which balance/harmony apply, “work-life balance” and a “balanced diet,” have received considerable attention in the literature. [17] Moreover, balance/harmony have salience among the public at large: a survey of lay perceptions of happiness across seven Western nations found participants primarily defined happiness as a condition of “psychological balance and harmony,” while a more extensive follow-up study similarly observed that the most prominent psychological definition was one of “inner harmony” (featuring themes of inner peace, contentment, and balance). [18]

Balance/harmony have been particularly associated with Eastern cultures, historically and currently. But does that mean they are overlooked or undervalued in the rest of the world? Possibly not.

However, empirical insight into how balance/harmony are linked with happiness around the globe is rare and under-studied, mainly due to a lack of data. This chapter redresses this lacuna by reporting on a unique data set collected as part of the 2020 Gallup World Poll, constituting the most thorough global approach thus far to these topics. Based on our reading of the literature, we approached the analysis guided by two interlinked hypotheses: (1) balance/harmony matter to all people, and (2) balance/harmony are dynamics at the heart of well-being. As will be seen, both hypotheses were corroborated to some extent.

This introductory section discusses what balance/harmony are in themselves, as well as the related phenomenon of low arousal positive states (e.g., peace and calm). We next introduce several new questions used to measure balance/harmony which were added to the Gallup World Poll in 2020 and look at their global distribution of responses. Third, we examine whether balance/harmony matter for happiness — and specifically life evaluation, the construct at the centre of this report — and then test for regional heterogeneity in the associations. The chapter concludes with some considerations of the overall significance of balance/harmony.

Defining Key Concepts

What is meant by balance/harmony? Like many concepts, their meanings are contested and debated. Moreover, their conceptualisations are usually tied to specific domains of life rather than defined in the abstract. In the arena of physiology, for instance, one review of the literature suggested that balance has been operationalised in two main ways: as a physical state (e.g., “in which the body is in equilibrium”) and as a function (e.g., “demanding continuous adjustments of muscle activity and joint position to keep the bodyweight above the base of support”). [19] Nevertheless, having reviewed the application and conceptualization of these concepts across different academic disciplines, we have formulated some generic orienting definitions — which apply across diverse contexts — to guide our analysis and discussion.

Balance is commonly used to mean that the various elements which constitute a phenomenon, and/or the various forces acting upon it, are in proportionality and/or equilibrium, often with an implication of stability, evenness, and poise.

These dynamics are frequently — but not only — applied to binary or dyadic phenomena. [20] Its etymology reflects this usage, deriving from the Latin bilanx, which denotes two (bi) scale pans (lanx). Substantively, these pairs may either be poles of a spectrum (e.g., hot-cold) or discrete categories that are frequently linked (e.g., work-life). Then, temporally, such connections can be synchronic (e.g., neither too hot nor cold) or diachronic (e.g., averaging good work-life balance over a career). In such cases, balance usually does not mean a crude calculation of averages, nor finding a simple mid-point on a spectrum, but skillfully finding the right point or amount, an ideal is known as the Goldilocks principle. [21] However, balance not only pertains to dyads but can also be applied to relationships among multiple phenomena, as per a “balanced diet,” for example.

Harmony is sometimes used synonymously with balance, but there are subtle differences. On our reading of the literature, a common distinguishing theme seems to be this: harmony means that the various elements which constitute a phenomenon, and/or the various forces acting upon it, cohere and complement one another, leading to an overall configuration which is appraised positively.

Empirical insight into how balance/harmony are linked with happiness around the globe is rare and under-studied, mainly due to a lack of data. This chapter redresses this lacuna by reporting on a unique data set collected as part of the 2020 Gallup World Poll, which constitutes the most complete global approach so far to these topics.

To appreciate how this differs subtly from balance, it helps to begin with its etymology, with the term deriving from the Latin harmonia, meaning joining or concord. This “concord” can then be obtained with respect to all manner of phenomena involving multiple elements. In classical Chinese and Greek philosophy, for instance, harmony was often elucidated with music, where it denotes a pleasing overall gestalt, involving an ordered arrangement of numerous notes which complement each other tonally and aesthetically. [22]

Thus, in this positive “concord”, one can potentially appreciate a subtle yet meaningful point of distinction between balance and harmony. Both are invariably interpreted as good (desirable, beneficial, etc.). However, balance is possibly more neutral and detached, while harmony is often “warmer” and even more positively valenced, with a more definite sense of flourishing. If one described a work team, for instance, as “balanced,” while this could imply a good mix of people and skills, it would not necessarily mean the colleagues got on well or thrived as a unit. But these latter qualities may well be brought to mind if the team were deemed “harmonious.”

Our understanding of balance/harmony is deepened by considering a nexus of psychological phenomena which are closely related, namely low arousal positive states (e.g., peace, calmness). Although balance/harmony apply across most life domains, as articulated in the introduction, they are often seen as intrinsically connected to low arousal states. As noted above, for example, in an international survey of lay perceptions of happiness, the most prominent psychological definition was one of “inner harmony,” which comprised themes of inner peace, contentment, and balance. [23]

Indeed, one way of interpreting experiences of balance/harmony overall is as being a form of low arousal subjective well-being. The concept of “subjective well-being,” as developed by Ed Diener and colleagues, is usually regarded as having two main dimensions: cognitive (i.e., life evaluation or satisfaction) and affective (i.e., positive affect). [24] Life evaluation tends not to imply any specific arousal level, while assessments of positive emotions usually focus on high arousal forms (such as enjoyment). [25] By contrast, one might suggest that experiences of balance and harmony constitute low arousal forms of cognitive evaluation (and so augment the idea of life evaluation). [26] In contrast, states like calmness and tranquillity constitute low arousal positive emotions, with peace having both cognitive and affective dimensions.

However, as with balance/harmony, these low arousal states have been relatively overlooked in the literature. Our understanding of these concepts — in themselves and in relation to each other — is currently lacking, hence the value of analyses like those reported here.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Balance/Harmony

At the start of the chapter, we suggested that although balance/harmony have attracted some academic interest (e.g., work-life balance), overall, they have not received the research attention they deserve. One potential explanation for this lacuna is that balance/harmony have traditionally been emphasised and valorized more in the East than the West. Since academia is widely appraised as Western-centric, this bias might explain the lack of prominence given to these topics. In this section, we delve into the literature behind these claims, looking in turn at five areas: (1) the Western-centricity of academia and the need for more cross-cultural research; (2) East versus West comparisons; (3) East versus West comparisons around balance/harmony; (4) issues with East versus West comparisons; and (5) the importance of balance/harmony more generally.

The place to begin is the increasingly voluble critique that happiness research, and academia generally, is Western-centric. An influential article in Nature in 2010, for example, suggested that the vast majority of research in psychology was conducted in cultures that are “WEIRD” (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic). [27] It cited an analysis showing that 96% of participants in studies in top psychology journals were from Western industrialised countries, even though these are home to only 12% of the world’s population. [28] Thus, given that most cultures are not comparably WEIRD, this limits the extent to which such research can be generalised. It is widely acknowledged that people are shaped, at least to some degree, by their cultural context, for instance, in terms of what they value and believe. [29] As such, there may be important differences among people depending on the extent to which their locale is indeed WEIRD. [30]

Given this background, there are increasing calls for more cross-cultural research. There is already a rich tradition of such research, of course. [31] Indeed, the World Happiness Report itself is an exemplar of such work, as is the Gallup World Poll. There is always scope for further development, though. One could argue, for instance, that the Gallup World Poll items used to assess happiness are Western-centric, influenced by the values and traditions of the USA in particular (where such concepts were formulated). With positive emotions, for example, the poll has focused on high arousal forms, such as enjoyment, which tend to receive more prominence in the West than low arousal forms; by contrast, Eastern cultures are seen as placing greater value on the latter, like peace and calmness, [32] as discussed below.

Thus, rather than only comparing cultures on concepts and metrics developed in Western contexts, there is increasing recognition of the importance of studying cultures through the prism of their own ideas and values, and of exploring cross-cultural differences in how people experience and interpret life. Again though, there has already been some excellent work in that respect. Arguably the most widely-studied cross-cultural dynamic is one that is germane to this chapter, namely the differences between Western and Eastern cultures. There are some issues with this East versus West distinction, as we discuss below. Nevertheless, it has received attention in thousands of studies across a wide range of interconnected phenomena.

Most prominent is the differentiation between individualism and collectivism — a dichotomy that can be interpreted in various ways, but perhaps above all is about whether a culture prioritises either the individual or the group. [33] By now, hundreds of studies appear to show that Western cultures lean towards the former and Eastern cultures towards the latter, [34] even if most of this work is more nuanced than this simple generalisation implies. [35] Then, beyond this distinction, numerous other psychosocial dynamics have been studied and mapped onto the East versus West binary. In terms of cognition, for instance, research has suggested the East tends to favour holistic and dialectical forms, and the West more linear, analytic modes. [36] Then, besides these, many other East versus West distinctions have been observed. [37]

Most relevantly, differences between East and West have been found in relation to balance/harmony. Before reviewing the empirical literature it is worth noting that, despite our hypothesis that these matter to all people, that Eastern cultures have historically been particularly attentive and receptive to ideas of balance/harmony, as exemplified by traditions like Confucianism and Taoism (e.g., as reflected in the latter’s yin-yang motif). [38] In that respect, a theoretical review described “yin-yang balance” as “a unique frame of thinking in East Asia that originated in China but is shared by most Asian countries.” [39] This frame relates to the holistic, dialectical form of cognition noted above and is contrasted, for example, with Aristotle’s formal “either/or” logic, which is viewed as dominant in the West. Much more could be said about this frame and the cultural traditions that support it, but it will suffice to note that Eastern cultures are widely viewed as having developed an especially strong affinity and preference for ideas and practices relating to balance/harmony.

This affinity is borne out in the empirical literature, although the relevant research is very sparse (e.g., compared to studies on individualism-collectivism). Most of this work focuses on low arousal states rather than balance/harmony per se. However, there is some emergent interest in the latter constructs in themselves. Research has suggested, for instance, that societal harmony is closely associated with happiness in Eastern cultures, to the point where such intersubjective harmony may be seen as actually constituting happiness itself (in contrast to Western cultures, which tend to construe happiness in more individualised ways as a personal subjective experience). [40] In that sense, happiness may be regarded more as an interdependent phenomenon in the East (rather than an independent one), as found in recent work on the Interdependent Happiness Scale. [41]

However, although the concepts are interlinked, most studies in this space focus on low arousal states rather than balance/harmony per se. A good example of such interlinking is that people from Eastern cultures are thought to generally place greater value on low rather than high arousal states (and vice versa for Western cultures), a preference which is then explained by valorization of balance/harmony in various ways. [42] One suggestion is that high arousal positive states are liable to be interpreted in the East as self-aggrandizing and therefore disruptive of social harmony, whereas low arousal states are more conducive to such harmony. [43] A related interpretation is that low arousal states are in themselves more reflective of balance/harmony (compared to high arousal ones), insofar as such emotions invoke balance-related notions such as equilibrium and equanimity. [44]

So, there is a clear case for thinking that balance/harmony may be more valued in the East than the West. However, while it is important to be cognizant of such cross-cultural differences, we must also be wary of broad generalisations. This is especially so when these are made based on very narrow samples. Indeed, most studies in this arena only involve college students (as noted in endnote 42) — as indeed does psychological research more broadly — which is hardly a sufficient basis on which to draw conclusions about vast regions like the “West.” Moreover, as Edward Said argued in his classic text Orientalism, the very notions of West and East are problematic constructions that homogenise and obscure the dynamic complexity of both areas. [45] Fortunately, cross-cultural scholars are generally aware of and responsive to these critiques and the need to attend to regional nuances. As noted above with the individualism-collectivism distinction, for example, many recent analyses have uncovered subtle, fine-grained differences among Eastern and Western countries.