World health organization age classification

World health organization age classification

Everyone knows that the elderly – it is the young who are beginning to age. Then in the human body irreversible changes occur. However, graying hair, wrinkles and shortness of breath are not always talking about the onset of old age. But how to determine the age when a person can be attributed to the category of the elderly?

Different time-different opinions?

It was once thought that old age – when a person has exceeded 20. We remember a lot of vivid historical examples where young people were married after reaching the age of 12-13 years. By the standards of the middle ages woman in 20 years was considered old. Today, however, not the middle ages. A lot has changed.

Later, this figure had been changed several times and the young were considered to be twenty people. This age marks the beginning of independent life, so flourishing, youth.

Modern views on age

In modern society again, everything somehow changed. And today, most young people did not hesitate to rank as the elderly those who barely crossed the thirties. The proof is the fact that employers are quite wary of applicants older than 35. And what can we say about those who have crossed 40?

But, it would seem that by this age, a person acquires a certain confidence, life experience, including professional. At this age he has a solid stance, clear goals. This is the age when people are able to realistically assess their strengths and take responsibility for their own actions. And suddenly, the verdict is: “Older”. What age can be considered individual elderly, we will try to understand.

How relevant today, drugs against worms in humans? What kind of creatures these worms, what are modern methods of treatment? We will try to answer these questions, since ignorance in this area is undesirable. Imagine a mummy, which is misleading in k.

Male impotence is a pathological condition associated with abnormal physiological capacity of the penis to reginout and bring sexual partner pleasure in bed.sex impotenceimpotence may not men to pass unnoticed – it usually spoils his nervous sy.

Developmental milestones

Representatives of the Russian Academy of medical Sciences say that recently there have been significant changes in the determination of biological age of a person. To explore these and many other changes occurring with the person, there is world health organization-who. Thus, the classification of the age of the person who says the following:

All who were fortunate enough to cross this threshold are considered to be long-lived. Unfortunately, up to 90, and especially 100 to live a few. The reason for this are various diseases that afflict people, the environmental situation and living conditions.

So what is it? Older age according to the who classification is much younger?

What is shown in polls

According to opinion polls, held annually in different countries, the people themselves are not going to grow old. And ready to identify themselves to the elderly only when they reach the age of 60-65 years. Apparently here originate bills to increase the retirement age.

Older people, however, need to devote more time to their health. In addition, the reduced attention and speed of information perception is not always possible for people 60 years to adapt quickly to changing situations. Of particular relevance it assumes in the conditions of scientific-technical progress. People who have reached a certain age it is sometimes difficult to master innovative technologies. But few think about the fact that for many people this is the strongest psychological trauma. They suddenly begin to feel their worthlessness, uselessness. This exacerbates the already heightened situation of reassessment of the age.

My years-my wealth

Classification of age who is not an absolute criterion to assign the person to a specific age category. It is not only the number of years characterizes the human condition. It is appropriate to recall the famous saying that says that a man is as old as he feels. Perhaps this expression to a greater extent characterizes the age of the person than the age classification of the who. It is related to the emotional condition of the person and with the degree of deterioration of the organism.

Unfortunately, the disease plaguing and harassing people, do not ask age. They are affected equally and the elderly, and children. It depends on many factors, including the condition of the body, immunity and living conditions. And, of course, from the way the person relates to their health. When something is not fully cured of the disease, and lack of proper rest, poor nutrition-all this and more pretty much makes the body.

Old age – for many grunts, poor memory, a whole bunch of chronic diseases. However, all of these weaknesses can be characterized and relatively young man. Today, it is not a criterion in order to classify the person to a specific age category.

The Crisis of middle age. What it the threshold?

Everyone knows such a thing as a midlife crisis. And who can answer the question, at what age it occurs more frequently? Before to define this age, let’s deal with the concept.

Under the crisis here refers to a time when a person begins to rethink values, beliefs, evaluate your life and your actions. It’s probably a phase in life and occurs when the experience of human life, experience, mistakes and frustration. Therefore, this life stage is often accompanied by emotional instability, even a deep and prolonged depression.

The Onset of such a crisis inevitable, it can last from several months to several years. And its duration depends not only from individual to individual and from his past life and from the profession, family environments and other factors. A emerge victorious from this conflict of life. And then the middle age gives way to aging. But it can also happen that the contractions go older and lost interest in life people who haven’t reached 50.

That says world health organization

As we have considered above, older age according to the who classification falls within the range from 60 to 75 years. According to the results of sociological researches, the representatives of this age category are young at heart and not going to burn themselves in the elderly. By the way, according to the same research conducted ten years ago, to the old carried all under the age of 50 years or more. The current classification of age by the who shows that people middle age. And it is quite possible that this category will only younger.

Few people in her youth think about what is the age considered elderly. And, crossing one milestone after another, people understand that at any age «life begins”. Only after accumulating a huge experience, people begin to think about how to prolong youth. Sometimes it turns into a real fight with age.

Signs of aging

The Elderly in the who is characterized by the fact that people have a reduction in vitality. What does it mean? Older people become sedentary, gain weight chronic diseases, they suffer from a reduced attentiveness, memory worsens.

However, older age according to the who classification, it is not just the age range. Researchers long ago came to the conclusion that the aging process takes place in two areas: physiological and psychological.

Senescence

With regard to physiological aging, it is the most clear and visible to others. As with the human body there are certain irreversible changes which are noticeable to himself and others. In the body everything changes. The skin becomes dry and loose, it causes wrinkles. The bones become brittle and because of this, the probability of fracture increases. Hair are discolored, broken and often falls. Of course, for people who want to keep their youth, many of these problems are solvable. There are various cosmetic products and procedures which, if correct and regular use can disguise visible changes. But these changes sooner or later will become visible.

Psychological aging

Psychological aging might not be as noticeable to others, but it is not always so. The elderly often varies greatly in nature. They become inattentive, irritable, tired quickly. And it happens often precisely because they see the manifestation of physiological aging. They not in forces to affect irreversible processes in the body and because of this, often experience deep emotional drama.

So what is the age considered elderly?

Due To the fact that every human body has its own characteristics, such changes occur in all different ways. And comes physiological.

Article in other languages:

later this figure several times changed and young people were considered to be twenty years.It is this age symbolizes the beginning of an independent life, and thus blossoming youth.

Modern views on the age

In modern society, again somehow changed.Today, most of the young people did not hesitate to classify the elderly who barely stepped over thirty years abroad.Proof of this is the fact that employers are quite wary of job seekers older than 35. And what can we say about those who have crossed 40?

But, it would seem, at this age the person gets some confidence, experience, including professional.At this age, he has a solid stance, clear goals.This is the age when a person is able to realistically assess their strength and take responsibility for their own actions.And suddenly, the verdict is: «The elderly».At what age can count the individual seniors, and we try to understand.

age limit

all who were fortunate enough to cross this threshold are considered to be long-lived.Unfortunately, up to 90, and even more so few live to 100.The reason for this are the different diseases that affect people, the environmental situation and living conditions.

So what happens?With old age according to WHO classification is much younger?

What sociological studies show

According to opinion polls, held annually in different countries, the people themselves are not going to grow old.And willing to classify themselves to the elderly only when they reach the age of 60-65 years.Apparently here originate a bill to increase the retirement age.

Older people, however, need to devote more time to their health.In addition, decreased attention and speed of information perception is not always possible for people over 60 years to adapt quickly to the changing situation.Of particular relevance is assumed in the scientific and technical progress.People who have reached a certain age, it is sometimes difficult to develop innovative technologies.But few people think about the fact that for many people this is a strong psychological trauma.They suddenly begin to feel worthlessness, uselessness.This exacerbates the deterioration of the situation revaluation of age.

age WHO classification is not an absolute criterion for chargeability person to a certain age group.It is not only the number of years characterizes the human condition.It is appropriate to recall the famous proverb that says that a man as old as he feels himself.Perhaps this expression to a greater extent characterizes a person’s age rather than age WHO classification.This is due not only to the psycho-emotional state of the person and to the degree of deterioration of the body.

midlife crisis.What is it today, the threshold?

Everybody knows such a thing as a midlife crisis.And who can answer the question about the age at which it occurs most often?Before you define this age, let’s get with the concept.

Under the crisis is here meant such a moment, when a person begins to rethink the values, beliefs, estimates the lived life and his actions.Probably, such a period in my life and there comes a time when a man behind those years, experience, mistakes and disappointments.Therefore, the life span is often accompanied by emotional instability, even a deep and prolonged depression.

onset of such a crisis is inevitable, it can last from several months to several years.And its duration depends not only from individual to individual and from his past life, but also by profession, family situation and other factors.Many emerging victorious from the conflicts of this life.And while the average age of not giving way to aging.But it happens, and so that out of this battle aged and lost interest in the life of people who have not yet reached 50 years.

What does the World Health Organization

As we have already discussed above, the older age of the WHO classification falls in the range of 60 to 75 years.According to the results of sociological research, the representatives of this age group and the young at heart is not going to write itself in the elderly.By the way, according to the same study, conducted ten years ago, all attributed to the elderly and those with 50 years or more.The current classification of the age of the WHO shows that this middle-aged people.And it is not excluded that this category will only younger.

Few youth thinks about what age is considered elderly.It was only over the years, crossing one milestone after another, people realize that at any age, «life is just beginning.»Only accumulated great experience, people start to think about how to stay young.Sometimes it turns into a real fight with age.

signs of aging

Old age is characterized by the WHO, that people have a decrease in vitality.What does this mean?Older people become sedentary, gain a lot of chronic diseases have decreased attentiveness, memory deteriorates.

However, old age according to WHO classification, it is not just age limits.Researchers have long come to the conclusion that the aging process is happening as if in two directions: physiological and psychological.

senescence

Regarding the physiological aging, then it is most clear and noticeable to others.As with the human body there are certain irreversible changes that are noticeable to himself and others.The body is changing everything.The skin becomes dry and loose, it leads to the fact that there are wrinkles.Bones become brittle and because this increases the probability of fracture.Hair discolored, broken and often drop out.Of course, for people who are trying to preserve their youth, many of these problems are solvable.There are various cosmetic products and procedures with proper and regular use can mask the visible changes.But these changes will sooner or later become apparent.

Psychological aging

Psychological aging might not be noticeable to others, but it happens not always.Older people often vary greatly in nature.They become inattentive, irritable, quickly get tired.And it happens often it is because they see the manifestation of physiological aging.They can not affect the irreversible processes in the body and because of this often experience a deep emotional drama.

So what age is considered elderly?

Due to the fact that the body of each person is different, there are similar changes in all different ways.And there comes a physiological and psychological aging is not always at the same time.Strong-willed people, optimists can take your age and maintain an active lifestyle, thereby slowing down physiological aging.So to answer the question of what age is considered elderly, it is sometimes quite difficult.It is not always the number of past years is indicative of the state of man’s inner world.

Most people who look after their health, feel the first changes in your body and try to adapt to them, they reduce the negative manifestation.If you regularly deal with his health, then possibly move the approach of old age.Therefore, those who fall into the category of «old age» according to WHO classification, can not always feel that way.Or, on the contrary, those who have overcome the 65-year milestone, consider themselves very old man.

Therefore, it is useful to recall once more that the proverb says: «A man as old as he feels.»

The elderly age according to the WHO classification is how much? What age is elderly?

Everyone knows that the elderly is someone who is no longeryoung, who begins to grow old. Then in the human body there are irreversible changes. However, graying hair, wrinkles and shortness of breath do not always indicate the onset of old age. But how to determine the very age when a person can be ranked as an elderly person?

It used to be that older age iswhen the person has passed for 20. We remember a lot of vivid historical examples, when young people entered into marriage, having barely reached the age of 12-13 years. By the standards of the Middle Ages, a woman at the age of 20 was considered an old woman. However, today is not the Middle Ages. Much has changed.

Later this figure changed several times and young people began to be considered twenty years old. It is this age that symbolizes the beginning of an independent life, which means prosperity, youth.

Modern views on age

In a modern society again all somehowchanges. And today, most of the young people, without hesitation, will rank among the elderly those who have barely crossed the thirty-year boundary. Proof of this is the fact that employers are also wary of job seekers over 35. And what about those who stepped over 40?

But in fact, it would seem, to this age manacquires some kind of self-confidence, life experience, including professional. At this age, he has a firm life position, clear goals. This is the age when a person is able to really assess their strengths and be responsible for their own actions. And suddenly, as the verdict sounds: «Elderly.» At what age can the individual be considered elderly, we will try to understand.

Age boundaries

All who were fortunate enough to cross this bar,are considered long-livers. Unfortunately, up to 90, and even more so to 100 few live. The reason for this is the various diseases to which a person is exposed, the ecological situation, as well as the living conditions.

So what happens? What is the elderly age according to the WHO classification significantly younger?

What sociological research shows

According to sociological surveys, annuallyconducted in different countries, the people themselves are not going to grow old. And they are ready to consider themselves elderly only when they reach the age of 60-65 years. Apparently the bills on increasing the retirement age come from here.

Elderly people, however, need more timegive their health. In addition, the decline in attention and speed of information perception does not always allow people after 60 years to quickly adapt to the changing situation. This is especially important in the conditions of scientific and technological progress. People who have reached a certain age sometimes find it difficult to master innovative technologies. But few people think about the fact that for many people this is the strongest psychological trauma. They suddenly begin to feel worthless, unnecessary. This aggravates the already aggravated situation of revaluation of age.

My years are my wealth

Classification of age by WHO is notan absolute criterion for assigning a person to a certain age category. After all, not only the number of years characterizes a person’s condition. Here it is appropriate to recall a famous proverb that says that a person is as old as he feels himself. Probably, this expression is more indicative of a person’s age than the age classification of WHO. This is due not only to the psychoemotional state of a person and to the degree of deterioration of the body.

Elderly age is for many grumbling, badmemory, a whole bunch of chronic diseases. However, all the above disadvantages can also characterize a relatively young person. Today, this is far from being a criterion for placing a person in a certain age category.

Middle age crisis. What’s his threshold today?

Everyone is well aware of the notion of crisismiddle-aged. And who can answer the question about the age at which he often comes? Before you determine this age, let’s deal with the very notion.

Under the crisis here is understood such a time whena person begins to rethink values, beliefs, assess life lived and his actions. Probably, such a period in life also comes exactly when people have lived behind their years, experience, mistakes and disappointments. Therefore, this life period is often accompanied by emotional instability, even profound and prolonged depression.

The onset of such a crisis is inevitable, lastinghe can from several months to several years. And its duration depends not only on the individual characteristics of the person and on his lived life, but also on the profession, the situation in the family and other factors. Many come out victorious from this life collision. And then the average age does not give way to aging. But it also happens that out of this struggle come out aged and lost interest in life people who have not reached even 50 years.

What the World Health Organization says

As we have seen above,WHO classification falls within the range of 60 to 75 years. According to the results of sociological research, representatives of this age group are young at heart and are not going to write themselves down into old people. By the way, according to the same research carried out a dozen years ago, everyone who reached the age of 50 or more referred to the elderly. The current age classification by WHO shows that these are middle-aged people. And it is completely possible that this category will only be young.

Few in youth think about whatage is considered elderly. And only with the years, crossing one line after another, people understand that at any age «life is just beginning.» Only having accumulated a huge life experience, people start to think about how to prolong youth. Sometimes it turns into a real fight with age.

Signs of aging

The elderly age in WHO is characterized by the fact thatpeople are reduced life activity. What does this mean? Elderly people become inactive, acquire a lot of chronic diseases, they decrease care, memory worsens.

However, the old age according to the WHO classification, thisnot just the age range. Researchers have long come to the conclusion that the aging process takes place in two directions: physiological and psychological.

Physiological aging

As for physiological aging, itmost understandable and visible to others. Because with the human body there are certain irreversible changes that are visible to him, as well as others. Everything changes in the body. The skin becomes dry and flabby, this leads to the appearance of wrinkles. Bones become brittle and because of this the probability of fractures increases. Hair is discolored, broken and often falling out. Of course, for people trying to keep their youth, many of these problems are solvable. There are various cosmetic preparations and procedures that, if properly and regularly used, can mask visible changes. But these changes will sooner or later become noticeable.

Psychological aging

Psychological aging may not be sovisible to others, but this is not always the case. The elderly often change their character. They become inconsiderate, irritable, quickly get tired. And this happens often precisely because they observe the manifestation of the aging of the physiological. They are unable to influence the irreversible processes in the body and because of this often experience a deep emotional drama.

So what age is elderly?

Due to the fact that the body of each person hastheir characteristics, there are similar changes in all in different ways. And physiological and psychological aging is not always simultaneous. Strong in spirit people, optimists are able to take their age and maintain an active lifestyle, thereby slowing down the physiological aging. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to answer the question of what age is considered elderly. After all, not always the number of years lived is an indicator of the state of the inner world of man.

Often people who are monitoring their health,feel the first changes in their body and try to adapt to them, reduce their negative manifestation. If you regularly take care of your health, then you can move away the approach of old age. Therefore, those people who fall into the category of «old age» according to WHO classification, can not always feel that way. Or, on the contrary, those who overcome the 65-year boundary, consider themselves ancient old men.

Therefore, it will be superfluous to recall once again what folk wisdom says: «A person is so old for how long he feels himself».

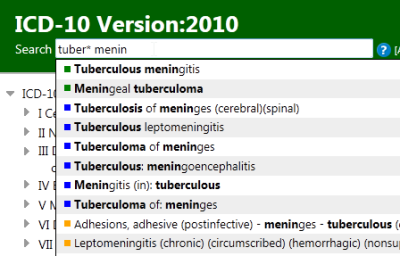

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD)

ICD serves a broad range of uses globally and provides critical knowledge on the extent, causes and consequences of human disease and death worldwide via data that is reported and coded with the ICD. Clinical terms coded with ICD are the main basis for health recording and statistics on disease in primary, secondary and tertiary care, as well as on cause of death certificates. These data and statistics support payment systems, service planning, administration of quality and safety, and health services research. Diagnostic guidance linked to categories of ICD also standardizes data collection and enables large scale research.

For more than a century, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) has been the basis for comparable statistics on causes of mortality and morbidity between places and over time. Originating in the 19 th century, the latest version of the ICD, ICD-11, was adopted by the 72 nd World Health Assembly in 2019 and came into effect on 1 st January 2022.

ICD purpose and uses

As a classification and terminology ICD-11:

ICD-11 Highlights

ICD-11 use cases

Uses of the ICD are diverse and widespread and much of what is known about the extent, causes and consequences of human disease worldwide relies on use of data classified according to ICD. See below just a few examples:

Classifications and Terminologies

WHO Family of International Classifications (FIC)

The WHO Family of International Classifications and Terminologies includes:

These Reference Classifications serve as the global standards for health data, clinical documentation and statistical aggregation.

Benefits of WHO-FIC

ICD-11, ICF and ICHI are key for effective knowledge representation and data transfer.

WHO Family of International Classifications (WHO-FIC) allows all healthcare workers (and patients) to communicate using one (technical) language.

In a hyper-connected world, WHO-FIC with their shared terminology are key for supporting natural language processing (NLP).

WHO-FIC with their shared terminology are key for effective text mining or text analytics (the process of deriving high-quality information from plain and unstructured text).

Used by

Reference Classifications

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and related health problems:

Diagnoses, injuries, findings, primary care.

The Foundation Component represents the entire WHO-FIC universe. It is a multidimensional collection of interconnected entities and synonyms. These entities consist of diseases, disorders, injuries, external causes, signs and symptoms, functional descriptions, interventions, and extension codes. ICD-11 statistical core (MMS) is derived from this foundation, ICF and ICHI will follow. Currently, with over hundred thousand entities and the ontological design of the foundation component, more than one million terms can be captured.

The Foundation Component also includes WHO terminologies such as:

Derived classifications are extensions of reference classifications, and are created for use within a specialty setting and are derived from the common foundation.

Related classifications

Related classifications are complementary to reference and derived classifications, and cover specialty areas not otherwise described in the Family of International Classifications (FIC).

WHO’s new International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) comes into effect

World Health Organization Age Classification

Age Standardization Of Rates: A New WHO Standard

Age 48 People Used

Classifications World Health Organization

World 42 People Used

and the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI). These Reference Classifications serve as the global standards for health data, clinical documentation and statistical aggregation. WHO-FIC Maintenance Platform. Benefits of WHO-FIC. ICD-11, ICF and ICHI are key for effective knowledge representation and data transfer. WHO Family of …

Who Age Group Classification 2021 Erinbethea.com

Who 49 People Used

Appropriate classifications of the age group for risk stratification are 0–14 years old (pediatric group), 15–47 years old (young group), 48–63 years old (middle age group) and ≥ 64 years old (elderly group).. What are the medical age groups? Personal health care (PHC) spending by type of good or service and by source of funding (private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, out …

What Is The WHO Standard Age Group Classification? Study.com

What 61 People Used

The WHO standard age group classification is a set of standardized definitions which places people into certain categories based on their age. Under See full answer below. Become a …

65 Years Old Is Still Young! Brilio

Years 36 People Used

PROVISIONAL GUIDELINES ON STANDARD INTERNATIONAL AGE

STANDARD 53 People Used

Classifications in the different subject areas consist of between 18 and 54 age groups, counting single years as separate age groups and excluding the classification of population by size and

Is Anyone Aware Of Acceptable Age Classification

Anyone 49 People Used

Old Age According To The Who Classification Is How Much

Old 57 People Used

That says world health organization As we have considered above, older age according to the who classification falls within the range from 60 to 75 years. According to the results of sociological researches, the representatives of this age category are young at heart and not going to burn themselves in the elderly.

World (WHO 20002025) Standard Standard Populations

Standard 52 People Used

The World (WHO 2000-2025) Standards database is provided for 18 and 19 age groups, as well as single ages. To derive the single ages from the 5-year age group proportions, we used the Beers «Ordinary» Formula. For more information on why we use single ages, refer to 2000 U.S. Standard Population vs. Standard Million.

Aging Fits Disease Criteria Used By World Health Organization

Aging 61 People Used

Aging meets World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria used for classifying conditions as diseases, according to a team of scientists from the International Longevity Alliance, the Biogerontology Research Foundation, and the Department of Risk Factor Prevention.

Table 1, World Health Organization (WHO) Classification Of

Table 59 People Used

Table 1 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of nutritional status of infants and children. Nutritional status: Age: birth to 5 years Indicator and cut-off value compared to the median of the WHO child growth standards a: Obese: Weight-for-length/height b or BMI-for-age >3 standard deviations (SD) of the median: Overweight: Weight-for-length/height b or BMI-for …

Ageing World Health Organization

Ageing 33 People Used

Ageing and Health in the Western Pacific. The Western Pacific Region has one of the largest and fastest growing older population in the world. There are over 700 million people aged 65 and over in the world and more than 240 million of them reside in the Western Pacific Region. This number is expected to double by 2050.

World Health Organization Age Classification

Age Standardization of Rates: A new WHO Standard

2 hours ago world population age-structure was constructed for the period 2000-2025. The use of an average world population, as well as a time series of observations, removes the effects of historical events such as wars and famine on population age composition. The terminal age group in the new WHO standard population has been extended out to 100 years and

World Health Organization Age Group Classification 2021

7 hours ago That says world health organization. As we have considered above, older age according to the who classification falls within the range from 60 to 75 years. According to the results of sociological researches, the representatives of this age category are young at heart and not going to burn themselves in the elderly. More › 491 People Used

7 hours ago Appropriate classifications of the age group for risk stratification are 0–14 years old (pediatric group), 15–47 years old (young group), 48–63 years old (middle age group) and ≥ 64 years old (elderly group).. What are the medical age groups? Personal health care (PHC) spending by type of good or service and by source of funding (private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, out …

World Health Organization Age Classification 2020

8 hours ago In 2016, the world health organization drafted a global health sector strategy on hiv. Isbn 978 92 4 156504 2 (nlm classification: By 2020, the number of people aged 60 years and older will outnumber children younger than 5 years. To make achievements towards these targets, the draft lists actions that countries and the who can take.

5 hours ago Benefits of WHO-FIC. ICD-11, ICF and ICHI are key for effective knowledge representation and data transfer.. WHO Family of International Classifications (WHO-FIC) allows all healthcare workers (and patients) to communicate using one (technical) language. In a hyper-connected world, WHO-FIC with their shared terminology are key for supporting natural language …

8 hours ago That says world health organization As we have considered above, older age according to the who classification falls within the range from 60 to 75 years. According to the results of sociological researches, the representatives of this age category are young at heart and not going to burn themselves in the elderly.

World health organization age group classification 2021

Just Now World Health Organisation (WHO) AGE Platform Isbn 978 92 4 156504 2 (nlm classification: By 2020, the number of people aged 60 years and older will outnumber children younger than 5 years. The terminal age group in the new WHO standard population has been extended out to 100 years and In 2016, the world health organization drafted a global

World Health Organization Age Classification 2020

6 hours ago World health organization age classification 2020. (iii) culture and leisure complex center for new class of elders; The who standard age group classification is a set of. However the health organization had done a new research recently, according to average health quality and life expectancy, and defined a new criterion that divides human age

Is anyone aware of acceptable age classification

Just Now The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations defines ‘Adolescents’ as individuals in the 10-19 years age group and ‘Youth’ as the 15-24 year age group. While ‘Young People’ covers the age range 10-24 years. As children up to the age of 18, most adolescents are protected under the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

8 hours ago Table 1. World Health Organization (WHO) classification of nutritional status of infants and children Nutritional status Age: birth to 5 years Indicator and cut-off value compared to the median of the WHO child growth standardsa Obese Weight-for-length/heightb or BMI-for-age >3 standard deviations (SD) of the median

PROVISIONAL GUIDELINES ON STANDARD INTERNATIONAL …

3 hours ago Classifications in the different subject areas consist of between 18 and 54 age groups, counting single years as separate age groups and excluding the classification of population by size and

Just Now Events. All →. WHO Global Health Facilities Database (GHFD) launch as part of this year’s UN Statistical Commission. 10 March 2022 15:00 – 16:30 CET. Country progress and way forward in phasing down the use of dental amalgam. 11 March 2022 15:30 – 16:30 CET. Sixty-sixth session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW 66) 14 – 25

United Nations has not classified 18 to 65-year-olds as

1 hours ago Social media posts in South Korea claim the United Nations (UN) has reclassified 18 to 65-year-olds as “youth”. The claim is false: representatives from various UN agencies said there was no such system, and UN publications define “youth” as …

World Health Organization Reference Curves

Author(s):

| Mercedes de Onis |

| Dr Mercedes de Onis is the Coordinator of the Growth Assessment and Surveillance Unit of the Department of Nutrition at WHO in Geneva. | |

| View Author’s Full Biography |

Introduction

Childhood overweight and obesity are major public health problems worldwide (1,2). Traditionally, a heavy child meant a healthy child, and the concept “bigger is better” was widely accepted. Today, this perception has drastically changed based on evidence that overweight and obesity in childhood are associated with a wide range of serious health complications and increased risk of premature illness and death later in life (2,3).

Anthropometric references play a central role in identifying children that are overweight or obese, or at risk of becoming so. The assessment of growth based on the appropriate use and interpretation of anthropometric indices is the most widely accepted technique to identify growth problems in individual children and assess the nutritional status of groups of children (4). The correct interpretation of accurate and reliable anthropometric measurements to assess risk, classify children according to variable degrees of overweight and obesity, or evaluate child growth trajectories, is heavily dependent on the use of appropriate growth curves to compare and interpret anthropometric values (5-10).

This chapter presents the growth charts the World Health Organization (WHO) developed for preschool age children (WHO Child Growth Standards) and school-aged children and adolescents (WHO Growth Reference for School-aged Children and Adolescents); it also discusses issues related to their appropriate use for identifying overweight and obese children.

WHO child growth standards (0-60 months)

In April 2006 the World Health Organization released new standards for assessing the growth and development of children from birth to five years of age (11,12). The new standards were developed to replace the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)/WHO international growth reference (13), whose limitations have been described in detail elsewhere (4,14).

The origin of the Child Growth Standards dates from the early 1990s when WHO conducted a comprehensive review of anthropometric references. The review showed that the growth pattern of healthy breastfed infants deviated significantly from the NCHS/WHO international reference (15,16). In particular, the reference was inadequate for assessing the growth pattern of healthy breastfed infants (17). An expert group recommended the development of new standards, adopting a novel approach that would describe how children should grow when free of disease and receiving care that followed healthy practices such as breastfeeding and non-smoking (18). This approach would permit the development of a normative standard as opposed to a reference that merely described how children grew in a particular place and time. Although standards and references both serve as a basis for comparison, each enables a different interpretation. Since a standard defines how children should grow, deviations from the pattern it describes are evidence of abnormal growth. A reference, on the other hand, does not provide as sound a basis for making such value judgments, although in practice references often are mistakenly used as standards.

Following the World Health Assembly’s endorsement of these recommendations in 1994, the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS) (19) was launched in 1997 to collect primary growth data that would allow the construction of new growth charts consistent with best health practices.

The MGRS, whose goal was to describe the growth of healthy children, was a population-based study conducted in six countries from diverse geographical regions: Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, and the USA (19). The study combined a longitudinal follow-up from birth to 24 months with a cross-sectional component of children aged 18–71 months. In the longitudinal component, mothers and newborns were enrolled at birth and visited at home a total of 21 times at weeks 1, 2, 4 and 6; monthly from 2–12 months; and bimonthly in the second year (19).

The study populations lived in socioeconomic conditions favourable to growth. The individual inclusion criteria were: no known health or environmental constraints to growth, mothers willing to follow MGRS feeding recommendations (i.e. exclusive or predominant breastfeeding for at least 4 months, introduction of complementary foods by 6 months of age, and continued breastfeeding to at least 12 months of age), no maternal smoking before and after delivery, single term birth, and absence of significant morbidity. Rigorously standardized methods of data collection and procedures for data management across sites yielded high-quality data (11,12).

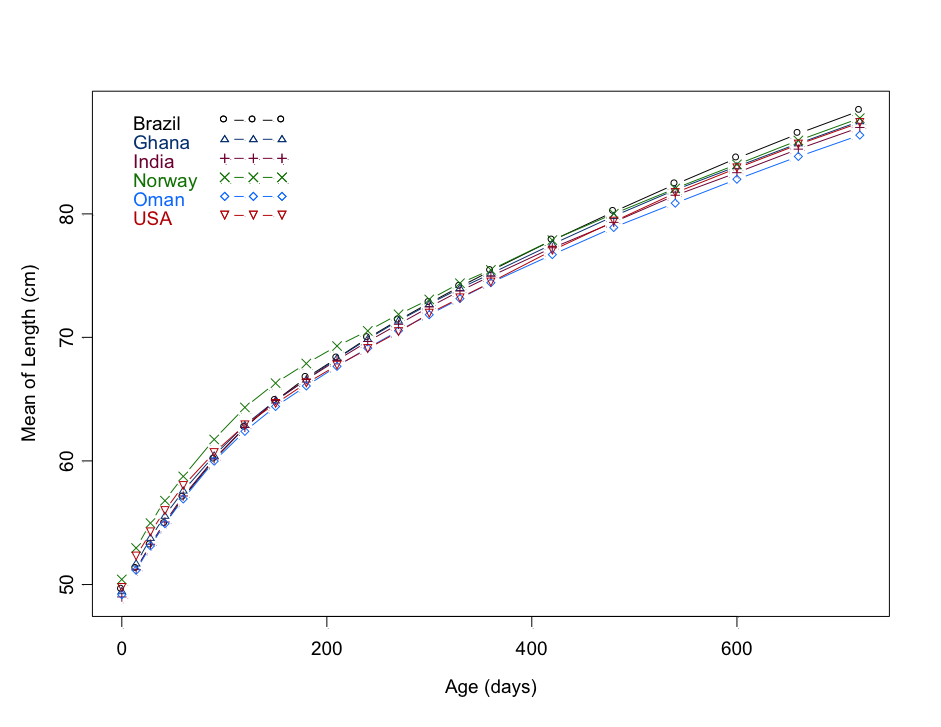

The length of children was strikingly similar among the six sites (Figure 1), with only about 3% of variability in length being due to inter-site differences compared to 70% for individuals within sites (20). The similarity in growth during early childhood across human populations means either a recent common origin as some suggest (21) or a strong selective advantage associated with the current pattern of growth and development across human environments. Data from all sites were pooled to construct the standards, following state-of-the-art statistical methodologies (11,22).

Figure 1. Mean length (cm) from birth to two years for the six WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study sites

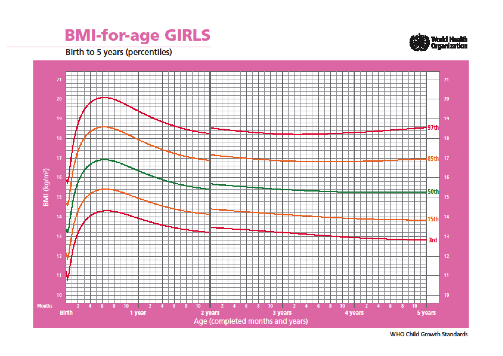

Weight-for-age, length/height-for-age, weight-for-length/height, and body mass index (BMI)-for-age percentile and z-score values were generated for boys and girls aged 0-60 months (11). Standards for head circumference, mid-upper arm circumference, and triceps and subscapular skinfolds were released in 2007 (23); and growth velocity standards for weight, length, and head circumference were issued in 2009 (24). Figure 2 presents a generic growth chart for body mass index-for-age in percentile values for girls aged 0–60 months. The full set of tables and charts is available at the growth standards website (www.who.int/childgrowth/en) together with tools like software, macros, and training materials that facilitate application. The disjunction observed at 24 months in the length/height-based charts represents the change from measuring recumbent length (i.e., lying down) to standing height in children below and above 2 years of age, respectively.

Figure 2. Body mass index-for-age in percentile values for girls aged 0 to 60 months

Detailed evaluation of the WHO standards as part of their introduction has provided an opportunity to assess their impact on child health programmes. Since their release in 2006, the standards have been widely implemented globally, with over 130 countries thus far having adopted them (25). Reasons for adoption include: 1) providing a more reliable tool for assessing growth that is consistent with the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding; 2) protecting and promoting breastfeeding; 3) enabling monitoring of malnutrition’s double burden, stunting and overweight; 4) promoting healthy growth and protecting the right of children to reach their full genetic potential; and 5) harmonizing national growth assessment systems. In adopting the WHO growth standards, countries have harmonized best practices in child growth assessment and established the breastfed infant as the norm against which to assess compliance with the right of children to achieve their full genetic growth potential.

The WHO standards provide an improved tool for monitoring the rapidly changing rate of growth in early infancy (9,26). They also demonstrate that healthy children from around the world who are raised in healthy environments and follow recommended feeding practices have strikingly similar patterns of growth. The ancestries of the children included in the WHO standards were widely diverse. They included people from Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Latin America. In this regard they are similar to growing numbers of populations with increasingly diverse ethnicities. These results indicate that we should expect the same potential for child growth in any country. They also imply that deviations from this pattern must be assumed to reflect adverse conditions that require correction, e.g. inadequate or lack of breastfeeding, nutrient-poor or energy-excessive complementary foods, unsanitary environments, deficient health services and/or poverty.

Technical and scientific research has validated the robustness of the WHO standards and improved understanding of the broad benefits of their use:

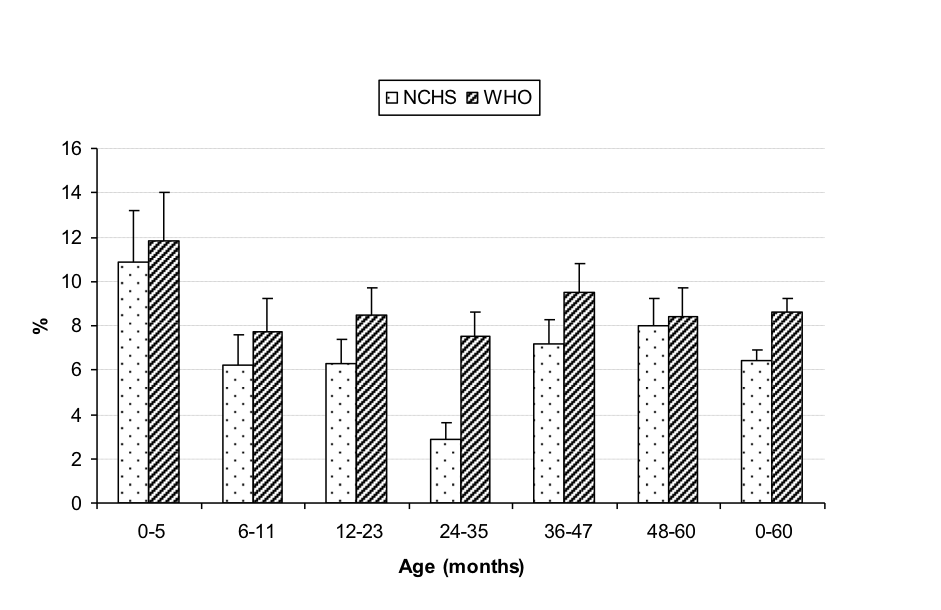

Figure 3. Prevalence of overweight (above +2 SD weight-for-length/height) by age based on the WHO standards and the NCHS reference in the Dominican Republic.

WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents (61 months-19 years)

Much less is known about the growth and nutritional status of school-age children and adolescents. Reasons for this lack of knowledge include the rapid changes in somatic growth, problems of dealing with variations in maturation, and difficulties in separating normal variations from those associated with health risks.

The release of the WHO standards for preschool children and increasing public health concern over childhood obesity stirred interest in developing appropriate growth curves for school-age children and adolescents. As countries proceeded to implement WHO growth standards for preschool children, the gap across all centiles between these standards and existing growth references for older children became a matter of concern. The 1977 NCHS reference (13) and more recent examples such as the CDC 2000 reference (33,34), the IOTF cut-off points (35) and other contemporary references (36-38) all suffer from a biological drawback characterised by weight-based curves, such as the BMI, that are markedly skewed to the right, thereby redefining overweight and obesity as ‘normal’ (39,40). The upward skewness of these references results in an underestimation of overweight and obesity and an overestimation of undernutrition (e.g., prevalence of thinness or children below the 3rd percentile) (41,42). The latter is worrisome as it might prompt the overfeeding of healthy, constitutionally small children.

A potential approach to overcoming this flaw would be to use lower cut-offs to screen for overweight and obesity (40). However, better still would be to use growth curves based on samples that have achieved expected linear growth while not being affected by excessive weight gain relative to linear growth (43). The case made for using a national reference has traditionally been that it is more representative of a given country’s children than any other reference could possibly be. But given the child obesity epidemic, this is no longer valid for weight or BMI. No sooner is a new reference produced than it is out of date.

The need to harmonise growth assessment tools, conceptually and pragmatically, prompted evaluation of the feasibility of developing a single international growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents (41). Recognising the limitations of existing reference curves (e.g. the NCHS/WHO growth reference, the CDC 2000 growth charts, and the IOTF cut-offs) for assessing childhood obesity, the expert group recommended that appropriate growth curves for these age groups be developed for clinical and public health applications. It also agreed that a multicentre study, similar to that leading to the development of the WHO Child Growth Standards from birth to 5 years of age, would not be feasible for older children because it would be impossible to control the dynamics of their environment. It was thus decided that a growth reference should be constructed for this age group using available historical data (43).

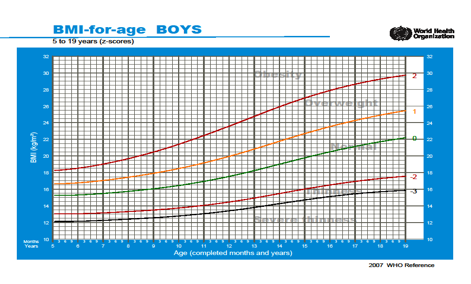

Following the expert group recommendations, WHO proceeded to reconstruct the 1977 NCHS/WHO growth reference for the period 5-19 years. It used the original sample (a non-obese sample with expected heights), supplemented with data from the WHO Child Growth Standards (to facilitate a smooth transition at 5 years), and applied state-of-the-art statistical methods (44). The new curves are closely aligned with the WHO Child Growth Standards at 5 years, and the recommended adult cut-offs for overweight and obesity at 19 years (BMI of 25 and 30, respectively)(Figure 4). The full set of tables and charts for height, weight and BMI can be found at: www.who.int/growthref/en, including application tools such as software for clinicians and public health specialists (45).

Figure 4. WHO BMI-for-age cut-offs for defining obesity, overweight, thinness and severe thinness in school-age and adolescent boys

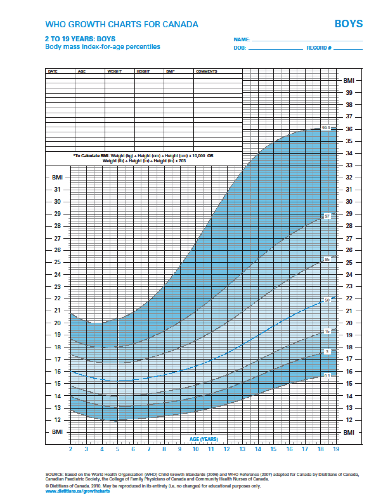

The WHO reference for school-age children and adolescents provides a suitable reference for the 5 to 19 years age group to be used in conjunction with the WHO Child Growth Standards from 0 to 5 years. Since its release in 2007 many countries have switched to using these charts including developed countries, for example Canada (Figure 5), Switzerland (46) and several others in Europe (47).

Figure 5. WHO Growth Charts for Canada. Body mass index-for-age percentiles, 2 to 19 years: boys

Defining childhood overweight and obesity in individuals and populations

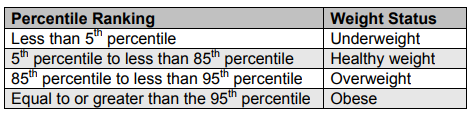

The classification of overweight and obesity is based not only on the use of an appropriate reference population with which to compare the individual child or community; it is also grounded in the selection of a suitable anthropometric indicator together with appropriate cut-off points to classify children according to severity levels which best identify risk of overweight/obesity-related morbidity and mortality.

The body mass index, a measure of body mass relative to height, has emerged as the most practical, universally applicable, inexpensive and non-invasive anthropometric indicator for classifying overweight and obesity (4). Although there is some reluctance to describe children as obese on the basis of BMI alone, i.e. without taking into account a more direct measure of body fat (48), recognition of the difficulties inherent in obtaining more proximate measures of body fat and lack of references to interpret them has resulted in BMI-for-age alone being used to define overweight and obesity. In its favour, increased BMI-for-age in childhood and adolescence is associated with higher percentages of body fat (49-51) and known risk factors for cardiovascular disease (52). It is important to note that, in preschool-age children, weight-for-length (below two years of age) and height (above two years of age) are also valid indicators for classifying young children as overweight and obese, and can be used instead of BMI-for-age as they yield very similar results (1).

The cut-off points WHO recommends for classifying overweight and obesity in preschool-age children (0-5 years) are detailed in the training course on child growth assessment (53). Children above +1SD are described as being “at risk of overweight”, above +2SD as overweight, and above +3SD as obese. WHO has opted for a cautious approach because young children are still growing in terms of height and there are few data on the functional significance of the upper end of the BMI-for-age distribution cut-offs at such young ages in healthy populations like the WHO standards (54). Caution is all the more important given the risks for very young children, in light of their nutrient requirements for growth and development, of being placed on restrictive diets.

For older children, the WHO adolescence BMI-for-age curves at 19 years closely coincide with the definitions for adult overweight (BMI 25) at +1 SD and adult obesity (BMI 30) at +2 SD, which were derived based on associations with mortality (4). As there were no similar associations with functional outcomes in the school age and adolescent periods, the BMI cut-offs at 19 years where tracked back along the +1SD and +2SD lines to age 5 years (44)(Figure 4). Recent research shows that obese and overweight school-age children and adolescents as defined by these BMI-for-age cut-offs are at substantially increased risk for adverse levels of several cardiovascular disease risk factors such as hypertension, high insulin, high HOMA, high triglycerides, low HDL-Cho, high LDL-Cho, and high uric acid (55). These results provide evidence that the WHO cut-offs for childhood overweight and obesity are well-suited to identifying children with metabolic and vascular risk.

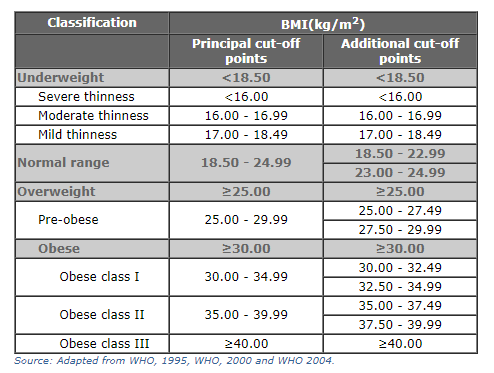

Table 1 summarizes the WHO classification of nutrition conditions in children and adolescents based on anthropometry.

Table 1: WHO Classification of nutrition conditions in children and adolescents based on anthropometry

| Classification | Condition | Age: Birth to 60 months 1,3 Indicator and cut-off | Age: 61 months to 19 years 2,3 Indicator and cut-off |

| Based on body mass index (BMI) | Possible risk of overweight | BMI-for-age (or weight-for-height) > 1SD | |

| Overweight | BMI-for-age (or weight-for-height) > 2SD | BMI-for-age >1SD(equivalent to BMI 25 kg/m 2 at 19 y) | |

| Obese | BMI-for-age (or weight-for-height) > 3SD | BMI-for-age >2SD (equivalent to BMI 30 kg/m 2 at 19 y) | |

| Thin | BMI-for-age  |

In assessing levels of severity for overweight and obesity in children under age 5 years, it is important to consider the actual value in kg of “excess” weight at different cut-offs for a still-growing 5-year-old in contrast to an adolescent who has reached adult height. For example, the “excess weight” carried by a boy of median height-for-age with a BMI-for-age of 2 SD at 19 years is 23.3 kg, while the equivalent “excess” for a boy at age 5 is 3.7 kg. Assuming that there is “excess weight” in both cases, its implications are likely greater for the former, who has reached his adult height, than for the latter, who could still grow (in terms of height) into his weight (56). When evaluating young children, clinicians might even prefer to avoid classifying a child at this age (0-5 years), and focus instead on the individual growth trajectory and the clinical assessment. Clinicians can also assess more proximate measures of body fat in individual children such as the triceps and subscapular skinfolds for which WHO standards are also available (24,26).

Conclusion

Growth curves are an essential tool in paediatric practice. Their value resides in helping to determine the degree to which physiological needs for growth and development are being met during the important childhood period. However, their usefulness goes far beyond assessing children’s nutritional status. Many governmental and international intergovernmental and nongovernmental agencies rely on growth charts for assessing the general well-being of populations, formulating health and related policies, and planning interventions and monitoring their effectiveness.

Accurate interpretation of child growth depends on prescriptive standards or, if unavailable, on reference data that accurately estimate the prevalence of overweight and obesity. Using the right growth curves is crucial since the accurate evaluation of growth trajectories and the appropriate choice of interventions to improve child health are determined on this basis.

There is broad international consensus concerning the utility of the WHO Child Growth Standards for assessing the growth of children 0 to 5 years of age. The standards are derived from children who were raised in environments that minimised constraints to growth such as poor diets and infection. In addition, their mothers followed healthy practices such as breastfeeding and not smoking during and after pregnancy. The standards depict normal human growth under optimal environmental conditions and can be used to assess children everywhere, regardless of ethnicity, socioeconomic status and type of feeding. They also demonstrate that healthy children from around the world who are raised in healthy environments and follow recommended feeding practices have strikingly similar patterns of growth.

The International Pediatric Association (57) and several other national and international professional associations have endorsed the use of the WHO growth standards. The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) (42,58) has also recommended their use in Europe. According to ESPGHAN, infants who are breastfed for the first 12 months of life show a slower growth pattern during infancy, which is likely to be associated with less obesity and improved health later in life. Another justification for their recommendation is that use of the standards has the potential to encourage prolonged breastfeeding and increase awareness about early obesity (42).

To complement the growth standards for under-five children, WHO developed a growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. The reference’s curves are closely aligned with the WHO Child Growth Standards at 5 years, and the recommended adult cut-offs for overweight and obesity at 19 years. They fill the growth-curve gap and provide an appropriate reference for the 5 to 19 years age group. Obesity and overweight defined using the WHO BMI-for-age cut-offs identify children with higher metabolic and vascular risk, while emphasising the importance of preventing overweight and obesity in childhood to reduce cardiovascular risk.

As a final note, it is essential that the same reference data be used in assessing both individuals (clinical use) and populations (health planning use) to ensure coherence between what paediatricians see in their daily practice and the population-based data health planners use in designing treatment and preventive services.

Note: WHO holds the copyright for the WHO Child Growth Standards and the WHO Growth Reference for School-aged Children and Adolescents.

Mental Health

In this entry we present the latest estimates of mental health disorder prevalence and the associated disease burden. Most of the estimates presented in this entry are produced by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and reported in their flagship Global Burden of Disease study.

For 2017 this study estimates that 792 million people lived with a mental health disorder. This is slightly more than one in ten people globally (10.7%)

Mental health disorders are complex and can take many forms. The underlying sources of the data presented in this entry apply specific definitions (which we describe in each relevant section), typically in accordance with WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). This broad definition incorporates many forms, including depression, anxiety, bipolar, eating disorders and schizophrenia.

Mental health disorders remain widely under-reported — in our section on Data Quality & Definitions we discuss the challenges of dealing with this data. This is true across all countries, but particularly at lower incomes where data is scarcer, and there is less attention and treatment for mental health disorders. Figures presented in this entry should be taken as estimates of mental health disorder prevalence — they do not reflect diagnosis data (which would provide the global perspective on diagnosis, rather than actual prevalence differences), but are imputed from a combination of medical, epidemiological data, surveys and meta-regression modelling where raw data is unavailable. Further information can be found here.

It is also important to keep in mind that the uncertainty of the data on mental health is generally high so we should be cautious about interpreting changes over time and differences between countries.

The data shown in this entry demonstrate that mental health disorders are common everywhere. Improving awareness, recognition, support and treatment for this range of disorders should therefore be an essential focus for global health.

The table here provides a summary of the data which follows on mental health and substance use disorders. Clicking on a given disorder will take you to the relevant section for further data and information.

Related entries:

The Global Burden of Disease study aggregates substance use disorders (alcohol and drug use disorders) with mental health disorders in many statistics. In the discussion of the prevalence we have followed this practice, but we will change it in future updates of this research.

We address substance use disorders (alcohol and drug use disorders) in separate entries on Substance Use and Alcohol Consumption.

| Disorder | Share of global population with disorder (2017) |

|---|

[difference across countries]

11.9% females

All our interactive charts on Mental Health

Empirical View

Prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders

The predominant focus of this entry is the prevalence and impacts of mental health disorders (with Substance Use and Alcohol Use disorders covered in individual entries). However, it is useful as introduction to understand the total prevalence and disease burden which results from the broad IHME and WHO category of ‘mental health and substance use disorders’. This category comprises a range of disorders including depression, anxiety, bipolar, eating disorders, schizophrenia, intellectual developmental disability, and alcohol and drug use disorders.

Mental and substance use disorders are common globally

In the map we see that globally, mental and substance use disorders are very common: around 1-in-7 people (15%) have one or more mental or substance use disorders.

Click to open interactive version

Prevalence of mental health disorders by disorder type

It’s estimated that 970 million people worldwide had a mental or substance use disorder in 2017. The largest number of people had an anxiety disorder, estimated at around 4 percent of the population.

Click to open interactive version

Prevalence of mental health disorders by genders

The scatterplot compares the prevalence of these disorders between males and females. Taken together we see that in most countries this group of disorders is more common for women than for men. However, as is shown later in this entry and in our entries on Substance Use and Alcohol, this varies significantly by disorder type: on average, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and bipolar disorder is more prevalent in women. Gender differences in schizophrenia prevalence are mixed across countries, but it is typically more common in men. Alcohol and drug use disorders are more common in men.

Click to open interactive version

Deaths from mental health and substance use disorders

The direct death toll from mental health and substance use disorders is typically low. In this entry, the only direct death estimates result from eating disorders, which occur through malnutrition and related health complications. Direct deaths can also result from alcohol and substance use disorders; these are covered in our entry on Substance Use.

However, mental health disorders are also attributed to significant number of indirect deaths through suicide and self-harm. Suicide deaths are strongly linked — although not always attributed to — mental health disorders. We discuss the evidence of this link between mental health and suicide in detail later in this entry.

In high-income countries, meta-analyses suggest that up to 90 percent of suicide deaths result from underlying mental and substance use disorders. However, in middle to lower-income countries there is evidence that this figure is notably lower. A study by Ferrari et al. (2015) attempted to determine the share disease burden from suicide which could be attributed to mental health or substance use disorders. 1

Based on review across a number of meta-analysis studies the authors estimated that only 68 percent of suicides across China, Taiwan and India were attributed to mental health and substance use disorders. Here, studies suggest a large number of suicides result from the ‘dysphoric affect’ and ‘impulsivity’ (which are not defined as a mental and substance use disorder). It is important to understand the differing nature of self-harm methods between countries; in these countries a high percentage of self-harming behaviours are carried out through more lethal methods such as poisoning (often through pesticides) and self-immolation. This means many self-harming behaviours can prove fatal, even if there was no clear intent to die.

As a result, direct attribution of suicide deaths to mental health disorders is difficult. Nonetheless, it’s estimated that a large share of suicide deaths link back to mental health. Studies suggest that for an individual with depression the risk of suicide is around 20 times higher than an individual without.

Disease burden of mental health and substance use disorders

Health impacts are often measured in terms of total numbers of deaths, but a focus on mortality means that the burden of mental health disorders can be underestimated. 2 Measuring the health impact by mortality alone fails to capture the impact that mental health disorders have on an individual’s wellbeing. The ‘disease burden‘ – measured in Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) – considers not only the mortality associated with a disorder, but also years lived with disability or health burden. The map shows DALYs as a share of total disease burden; mental and substance use disorders account for around 5 percent of global disease burden in 2017, but this reaches up to 10 percent in several countries. These disorders have the highest contribution to overall health burden in Australia, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Click to open interactive version

Depression

Definition of depression

Depressive disorders occur with varying severity. The WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) define this set of disorders ranging from mild to moderate to severe. The IHME adopt such definitions by disaggregating to mild, persistent depression (dysthymia) and major depressive disorder (severe).

All forms of depressive disorder experience some of the following symptoms:

Mild persistent depression (dysthymia) tends to have the following diagnostic guidelines:

“Depressed mood, loss of interest and enjoyment, and increased fatiguability are usually regarded as the most typical symptoms of depression, and at least two of these, plus at least two of the other symptoms described on page 119 (for F32.-) should usually be present for a definite diagnosis. None of the symptoms should be present to an intense degree. Minimum duration of the whole episode is about 2 weeks. An individual with a mild depressive episode is usually distressed by the symptoms and has some difficulty in continuing with ordinary work and social activities, but will probably not cease to function completely.”

Severe depressive disorder tends to have the following diagnostic guidelines:

“In a severe depressive episode, the sufferer usually shows considerable distress or agitation, unless retardation is a marked feature. Loss of self-esteem or feelings of uselessness or guilt are likely to be prominent, and suicide is a distinct danger in particularly severe cases. It is presumed here that the somatic syndrome will almost always be present in a severe depressive episode. During a severe depressive episode it is very unlikely that the sufferer will be able to continue with social, work, or domestic activities, except to a very limited extent.”

The series of charts below present the latest global estimates of the prevalence and disease burden of depressive disorders. Depressive disorders, as defined by the underlying source, cover a spectrum of severity ranging from mild persistent depression (dysthymia) to major (severe) depressive disorder. The data presented below includes all forms of depression across this spectrum.

Prevalence of depressive disorders

The share of population with depression ranges mostly between 2% and 6% around the world today. Globally, older individuals (in the 70 years and older age bracket) have a higher risk of depression relative to other age groups.

Click to open interactive version

Click to open interactive version

In 2017, an estimated 264 million people in the world experienced depression. A breakdown of the number of people with depression by world region can be seen here and a country by country view on a world map is here.

In all countries the median estimate for the prevalence of depression is higher for women than for men.

DALYs from depression

The chart found here shows the health burden of depression as measured in Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) per 100,000. A time-series perspective on DALYs by age is here.

Depression is complicated – this is how our understanding of the condition has evolved over time

People often think of depression as a single, uniform condition – deep sadness and a loss of interest in the activities that someone usually enjoys. But depression is complicated and it’s difficult to define what it means in an objective way.

This is because depression is a condition of the mind: it is diagnosed based on people’s psychological symptoms and behavior, not from a brain scan or markers in their blood or DNA.

When we diagnose depression, we have to rely on people to recall their own symptoms. We have to trust that doctors will observe and probe their symptoms reliably. We have to analyze this information to understand what people with depression experience that other people don’t.

Our ability to do all of these things accurately has changed over time, and so has our understanding of depression.

This comes down to three factors.

First, many countries now screen for depression in the general population, not just in a subset of people who are seen by a small number of doctors. In many studies, researchers track patients over long periods of time to understand how the condition progresses.

Second, we use questionnaires and interviews that treat depression as a condition that can occur at different levels and change with time.

Third, we have better statistical tools to help us refine questionnaires and understand how symptoms are related to one another.

Let’s look at each of these factors in more detail before we explore how they have informed our understanding of depression.

Surveying depression in the general population

Depression traces back to a condition called ‘melancholia.’ The concept of melancholia itself shifted in meaning several times in history. In ancient Greek medicine, it referred to a general condition of sadness and fear. From the 16th century, it was generally considered a type of insanity, and symptoms such as delusions and suspicion became more of a focus in these descriptions. Some people with these symptoms would likely be diagnosed with schizophrenia today.

From the late 18th century onwards, these symptoms became less emphasized, while fatigue and distress became more central to the diagnosis. Over the same time, the word depression was increasingly used in descriptions of melancholia. Since the 20th century, melancholia has been the name given to a severe subtype of depression. 3

In the 19th century in Britain, for example, the diagnosis of melancholia was mainly used to decide who to admit to asylums. It was diagnosed based on the judgment of individual physicians who used different methods, and many asylums used broad definitions of suicidality. Talking about death, drinking too much alcohol, refusing food, having thoughts of guilt or damnation, having a fear of persecution, and any kind of self-harm could all be considered suicidal tendencies. 4

Different asylums in Britain used different classification systems. This meant that statistics were difficult to compare between regions and were controversial, even at the time. Asylums would only record the overall number of patients with each condition – they wouldn’t record the symptoms of individual patients. 5 In contrast, in Imperial Germany, detailed information about asylum patients was collected using census cards. 6

Some psychiatrists such as Emil Kraepelin and Philippe Pinel monitored people in asylums in a systematic way. They noted which symptoms they had and how their illness changed over long periods of time. With that information, they designed systems to classify people with disorders. 7

For example, Kraepelin noticed that some people with psychosis also had periods of depression, while others did not. He called the former condition ‘manic depression’ (which we would now understand as bipolar disorder or depression) and the latter ‘dementia praecox’ (which we now understand as schizophrenia).

These kinds of classifications began to be applied at large in asylums across Europe.

At the same time, psychologists began to devise questionnaires to measure people’s symptoms empirically. They developed various scales and tested them with college students before applying them to adults in the general population. Large organizations such as the American Psychological Association developed criteria that could be used to diagnose patients in a standardized way.

Depression is a condition that is increasingly recognized and surveyed in the population as a whole.

Now, we collect data on depression from two sources. First, we have data on diagnoses made by doctors. In many countries, doctors inquire about people’s symptoms and how much they correspond to the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). They also use tests to rule out medical conditions, such as thyroid disorders, that result in similar symptoms. Second, we have data on the severity of depression. This data is collected from patients and the general population, using many different questionnaires and rating scales. 8 But there are still gaps in our knowledge. Data is lacking especially in many poorer places around the world. Even within high-income countries, people with poorer health or severe depression are much less likely to respond to these community surveys or report their symptoms accurately. If we didn’t take this into account, we would underestimate the prevalence of depression in the population. 9

Measuring depression on levels

The second reason that we understand depression more accurately now is that we ask more nuanced questions about symptoms.

Depression as measured by Kraepelin focused only on whether symptoms were present or absent. But the measures that are used for screening or diagnosis today go much further. 10 Now, people are asked about how frequent or severe their symptoms are.

For example, if someone has trouble sleeping, how many days does that occur each week? If they feel guilt, how often do they feel guilty? How guilty do they feel?

Do they often think about things they did wrong a long time ago? Do they blame themselves for having depression, seeing it as punishment? Do they hear voices accusing them or see hallucinations that threaten them?

We can use more specific questions like this to rate each symptom on levels that relate to how frequent or severe they are. We can place possible answers on a range from, say, 0 to 3. A person’s scores across all the symptoms can then be added up to give a total, and we can use cut-offs to classify an episode as ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ depression.

This was a huge step forward. It meant we could find out if patients with mild depression tended to be different from those with severe depression. We could also find out if they responded differently to treatment.

Most importantly though, these ratings have allowed us to record subtle changes over time. Many of these scales were developed as antidepressants were discovered and psychotherapy became more widely used, and the scales were used to track how patients improved while on these treatments. With a crude diagnosis, it would be difficult to detect subtle improvements in patients. 11

What this means is that the way we conceptualize depression today is not as a fixed condition, but as something that can occur at varying degrees and that can potentially resolve.

People might experience symptoms on some days but not others, and they might have symptoms that become milder with time. The questionnaires we use probe symptoms in a way that measures how they might change, and how they might be treatable.

Analyzing depression with more rigour

We’ve seen how depression has been screened in the wider population and how it is measured in a more nuanced way.

But how would we find out whether these questionnaires were actually measuring depression? How would we know that people’s symptoms were being interpreted in a consistent way?

In the 19th and 20th centuries, statisticians began to develop techniques to measure many aspects of questionnaires, so they could refine them. They were interested in understanding how consistently the questions measured the same underlying concept.

They were also concerned with testing how people’s responses on a questionnaire reflected their behavior in the real world. They could do this, for example, by estimating how their scores on a depression questionnaire correlated with their ability to work or study.

They began to put more focus into understanding how much we could rely on the judgment of individual doctors, instead of treating them as infallible experts.

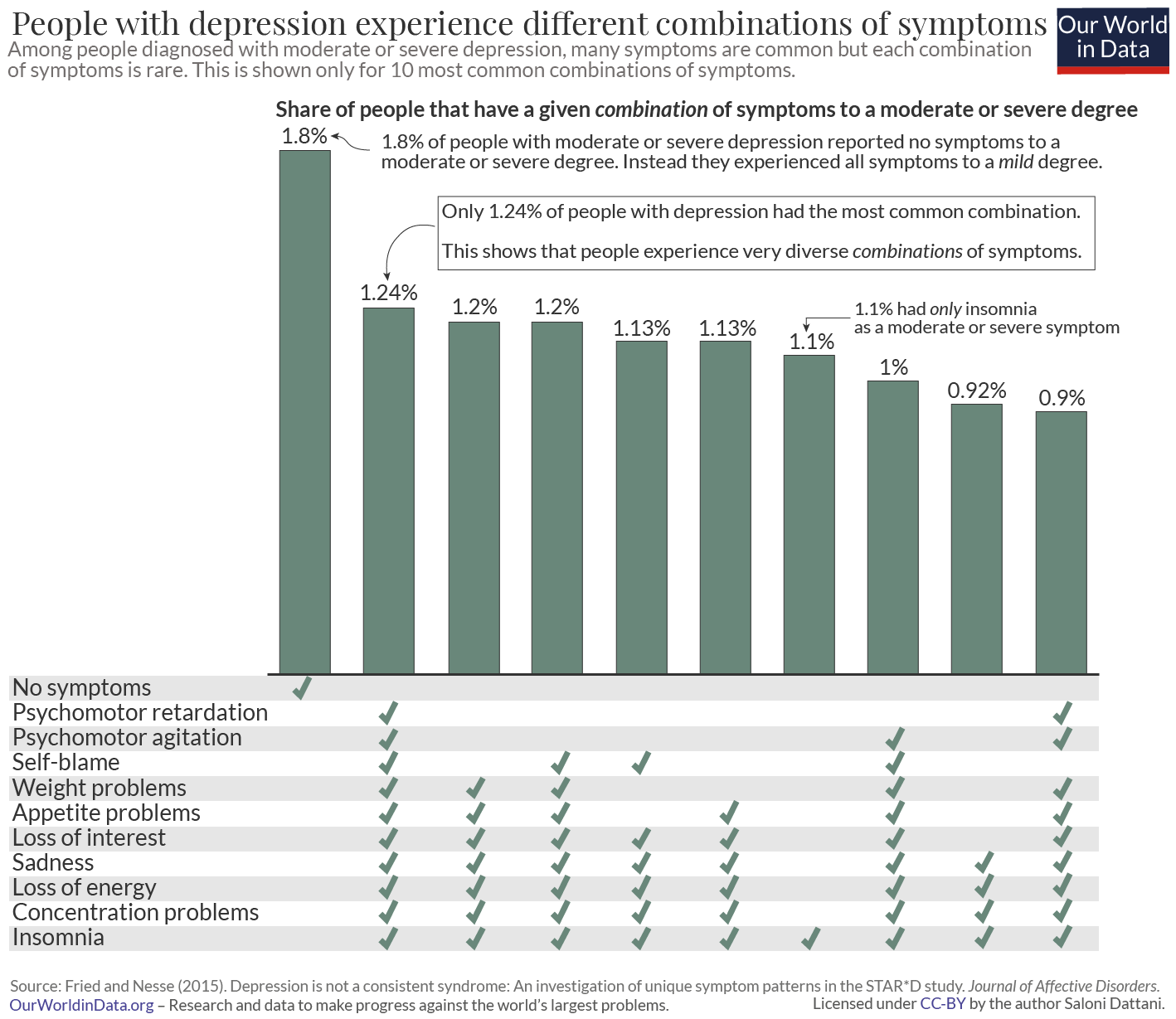

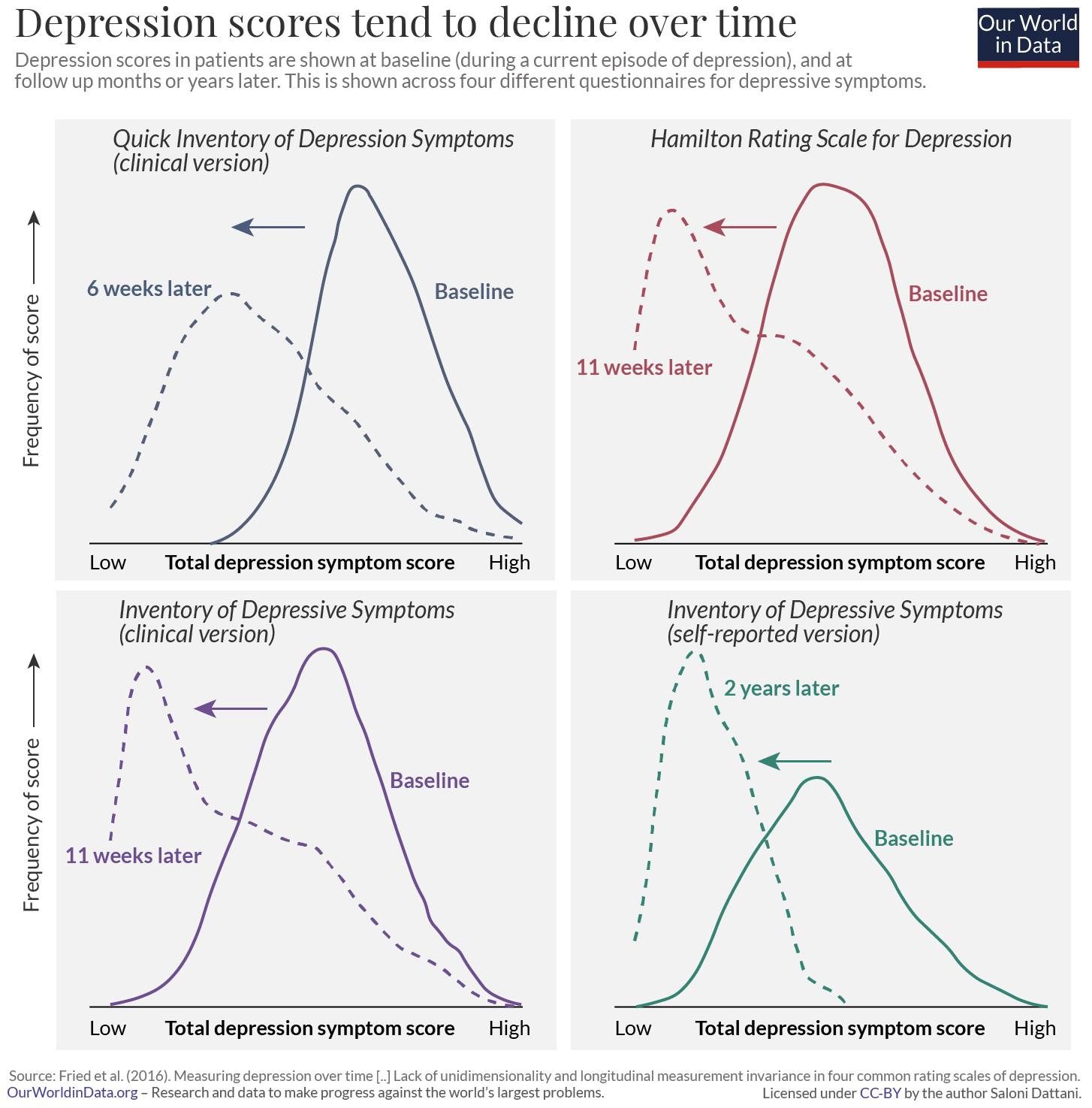

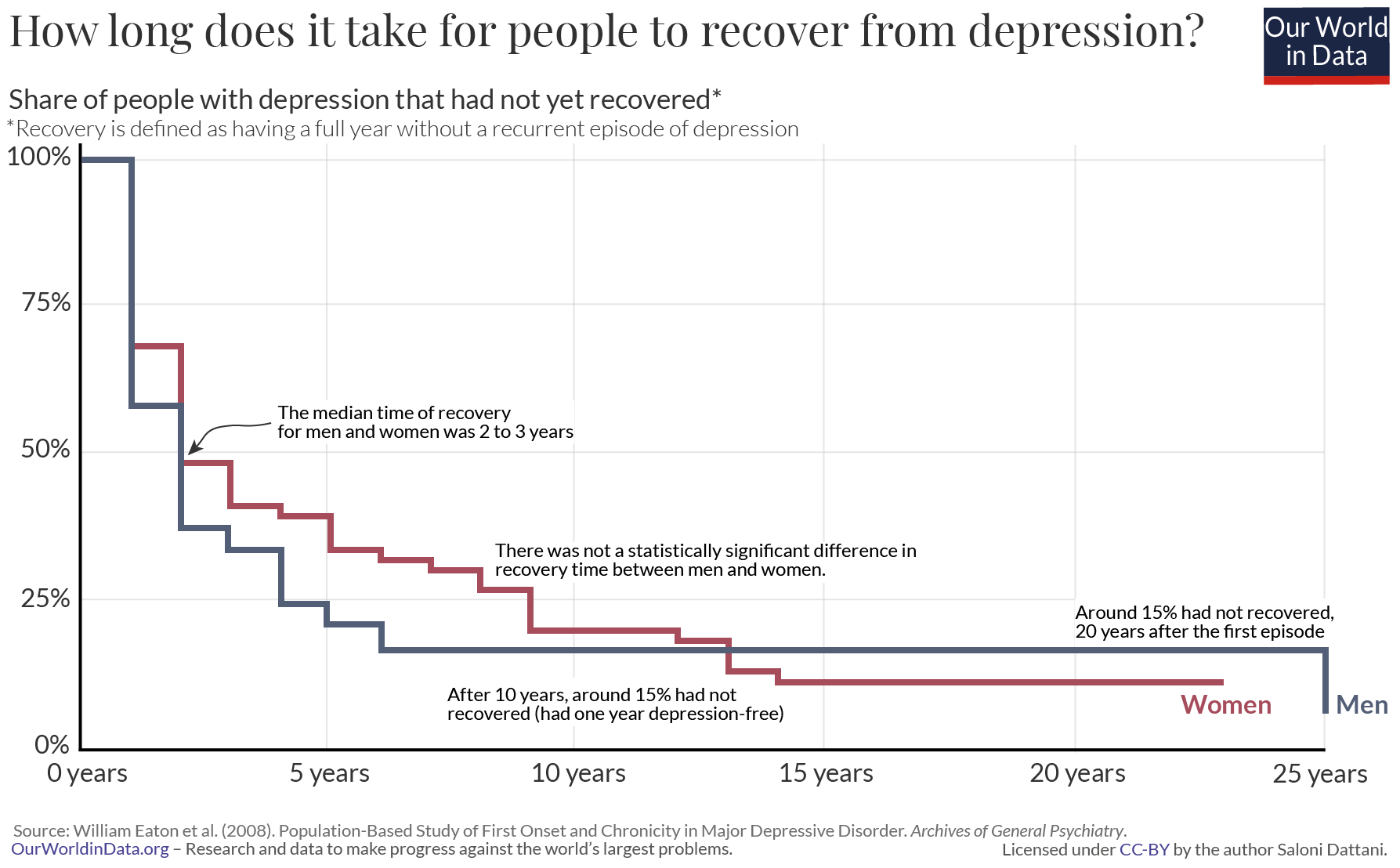

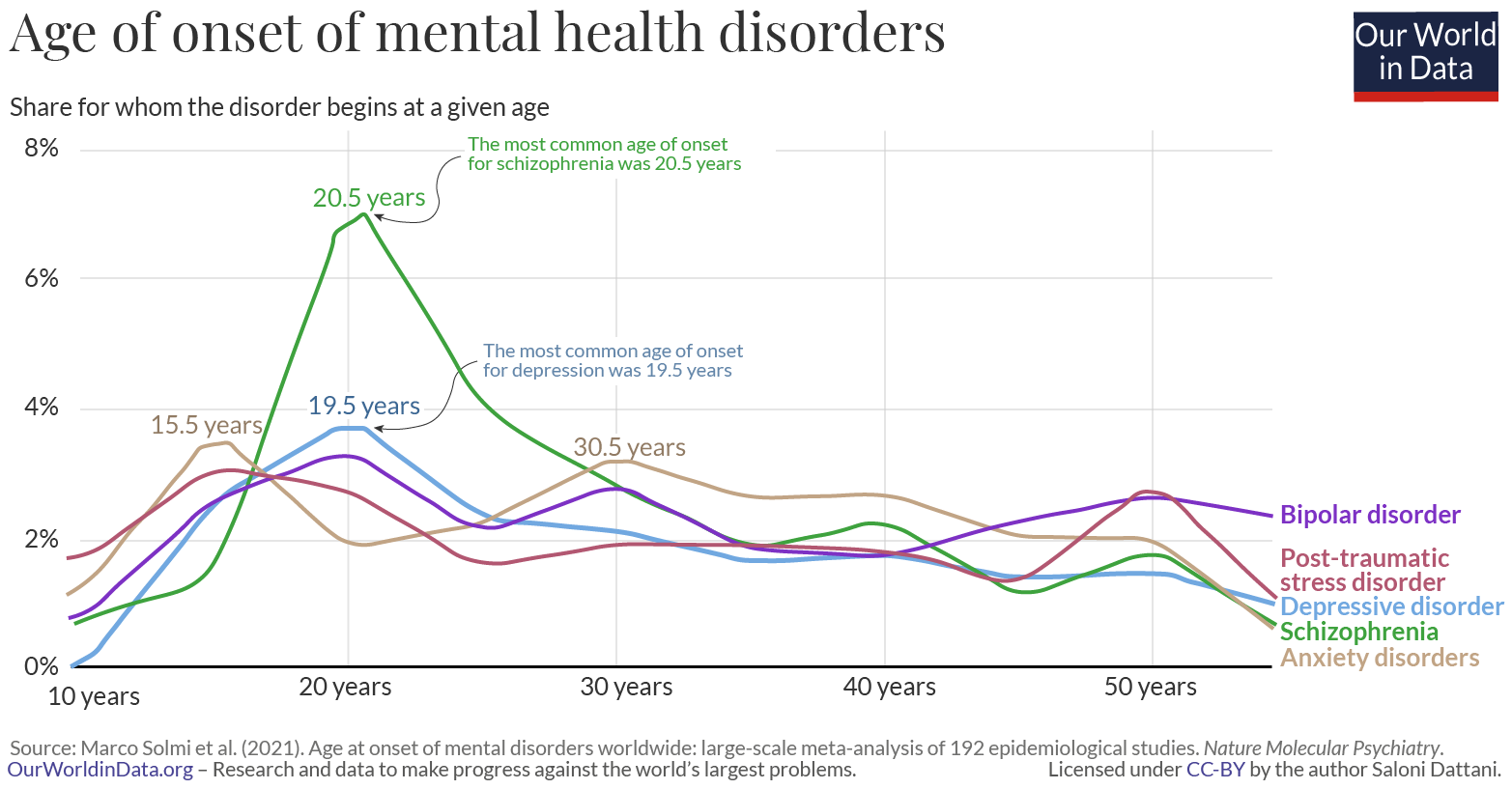

This was important because patients were included in clinical trials based on their scores on these questionnaires. If doctors had wildly different methods of scoring patients on the questionnaires, it would be very hard to compare patients with each other. It would also be hard to compare patients’ scores at the start of a trial to their scores at the end.